The study was written within the Think Tank Development Initiative for Ukraine (TTDI), carried out by the International Renaissance Foundation in partnership with the Think Tank Fund of the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE) with financial support of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, the International Renaissance Foundation, and the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE)

Peer review: Alyona Getmanchuk, Nicu Popescu

The team of contributors to this study includes: Leonid Litra, Sergiy Solodkyy, Kateryna Zarembo, Snizhana Diachenko, Tetiana Levoniuk

The author of the cartoon on the cover: Oleh Smal

CONTENT

- FOREWORD

- GOALS

- INSTRUMENTS

- BEST PRACTICES

- VULNERABILITIES OF RUSSIAN INSTRUMENTS

- POTENTIAL VULNERABILITIES IN EU COUNTRIES

- RECOMMENDATIONS

1. FOREWORD

The power of Russia’s manipulative mass media, the omnipotence of its secret service, its highly disruptive and widespread hacker attacks, its interference in western election campaigns… The impression might be that Russia is just collecting notches on its belt and that its power has no bounds. The odd cases of successful counters to Russia’s campaign against western democracies have remained largely outside systematic analysis.

The New Europe Center decided to fill this gap by analyzing the vulnerabilities of the hybrid war Russia is waging against the European Union. The findings of this study should become useful for further efforts to counter Russian interference and for cooperation between Ukraine and EU countries in order to minimize the impact of future hybrid interventions by Moscow. Examples of failures and of the weakening impact of Russia’s undermining activities are quite visible by now—indeed, they are so many that it is already possible to raise the entire question of the effectiveness of Russia’s interference. Has Russia reached the point of ‘atrophy of trophies’—where its sabotage and special ops are beginning to go flabby and failing to bring the desired results? This should inspire Ukraine and its partners to respond more robustly and more systematically.

The New Europe Center has studied the goals and instruments Russia has to forward its policy of subverting EU countries, but the main thing we did was study success stories—cases where Moscow’s hybrid campaigns were defeated. Whether that’s the failure of Russian media projects in Germany, the prolongation of Russian sanctions policies across the EU, or the exposure of Russian spies in Poland—all of these are just the tip of the iceberg of best practice in countering Russia’s hybrid war.

Examples of failures and of the weakening impact of Russia’s undermining activities are quite visible by now—indeed, they are so many that it is already possible to raise the entire question of the effectiveness of Russia’s interference – of ‘atrophy of trophies’

We chose six countries for this in-depth study: Germany, Italy, France, Greece, Poland, and Hungary. In terms of the level of Russian influence, they are all different — as well as in their successful resistance to Moscow’s interference. We understand that every success story that counters this interference, like every instrument in Russia’s bag of tricks, tends to be unique in nature and specific to the particular situation. This has made systematizing and comparative analysis a real challenge for the New Europe Center team of analysts. We also realized and took into account the methodological difficulties connected with conceptualizing and categorizing the phenomena we were looking at.

For instance, with the Lisa case in Germany, Russia’s footprint was obvious to the naked eye, whereas the conflicts between Poland or Hungary and Ukraine did not always yield direct evidence, even if Russia’s interest was obvious and overt. Other examples of methodological challenges that EU analysts pointed to included determining exactly what was the root cause for the failure of Russia’s subversive policy. Take Germany: why did Russia’s media campaign there fail utterly—because of the lack of professionalism in those same Russian media or because of Germany’s institutional, media and social immune system?

This study provides only the basic observations that are typical across all six countries. Our think-tank will also publish six separate, in-depth case studies for each of these countries. In addition, we will be expanding the list of EU countries to be studied, as Russia’s diminishing returns are being reflected in the growing number of new success stories, even in countries that seem to be most tolerant towards Moscow and its interference.

Based on interviews we held with some of the best researchers of Russia’s hybrid influence in the EU and using comparative analysis carried out by the New Europe Center, we have prepared recommendations for reinforcing Europe’s resistance to Moscow’s special ops. This NEC study could be especially useful to Ukraine’s government agencies, as well as to the governments of EU member countries—in short, all those who are interested in preserving democratic systems and rule of law in the face of the undeclared war that Russia is waging against them.

The New Europe Center would like to thank its colleagues in Ukraine and in the countries where the data for this report was collected. Altogether, we interviewed more than 50 analysts, journalists, diplomats, and politicians, who helped us understand the recipe for resistance in European societies confronted with Russia’s efforts to undermine them. Any positive marks given this report we are happy to share with the partners and colleagues who helped put it together, but any inaccuracies are exclusively the responsibility of the NEC analytical team. What’s more we are open to any observations and requests from readers, and will take them into account as we delve into this subject in greater depth.

2. GOALS

A study of Russian anti-Ukrainian subversion campaigns in six member states of the European Union and NATO showed that Russia has used different means to achieve similar goals in every country. But while Russia’s anti-Ukrainian policy is obviously just one component of its broader influence in the West, its overall goals in EU and NATO countries could also hurt Ukraine.

Thus, top goals of Russia’s subversive policy in EU countries include:

- Undermining European unity in general and specifically with regard to sanction policy against Russia. Russia’s support for anti-European political parties such as Liga in Italy, Alternative for Germany (AfD) in Germany, the National Front* and Unsubmissive France in France, and Golden Dawn in Greece; Russia stirs conflicts among neighbors such as Hungary and Poland with Ukraine and undermines trust between partners, such as diminishing trust within the EU towards Poland, Hungary and Italy. As a result of these actions European unity is shaken. It damages consensus building within the EU and NATO, decreases chances of confronting Russia with a united front, setting up conditions for successful “divide and rule” Russian policy.

- Destabilizing the EU and NATO. While linked to the previous goal and even similar in tools, this point is about subverting democracies in the EU and NATO members states, making them focus on their own internal problems and corrode them from within.

- Being legitimized and assertive in the international arena. Whether it is through maintaining high-level contacts—currently in those countries that are the subject of this study, there’s not one leader who is unwilling to shake hands with Vladimir Putin—, or by supporting authoritarian tendencies within European countries— which, of course, allows Russia to justify its own authoritarianism—, Russia’s aim is to prevent itself from being isolated in important international decision-making formats.

3. INSTRUMENTS

Russia employs a very diverse toolkit to influence European countries ranging from a number of hard tools like covert military threats, economic and energy blackmail, and soft ones like networks of Russian and pro-Russian agents, or cultural and academic links, to hybrid tools, such as media influence through disinformation.

Nevertheless, the contexts and environments for engagement differ from country to country across Europe. For instance, countries like Poland and Hungary, as the former members of the Warsaw Pact, have stronger society-wide resistance and resilience to Russian influence, but their shared history and Russia’s dominance has left Moscow with a vast collection of dossiers that contain compromising facts and allegations, making it possible to blackmail and “control” individual politicians and public figures. Germany, whose part was under Soviet control, is also not immune to such pressure. As an example, Matthias Warnig, the CEO of Nord Stream AG, is a former Stasi member.

In the EU’s major powers like France, Italy and Germany, the context is different: Russia enjoys wider public support there and capitalizes on its own history as a one-time “superpower.” Everything is further complicated by longlasting collective memories and traumas: while Poland is antagonistic towards Russia, especially since the 2010 Smolensk catastrophe, Germany is afraid of violence and escalation in Europe. Russia can play on both these sentiments. Covert interference of various sorts takes place in all countries but the methods are tailor-made.

Russia has a vast collection of dossiers that contain compromising facts and allegations, making it possible to blackmail and “control” individual politicians and public figures

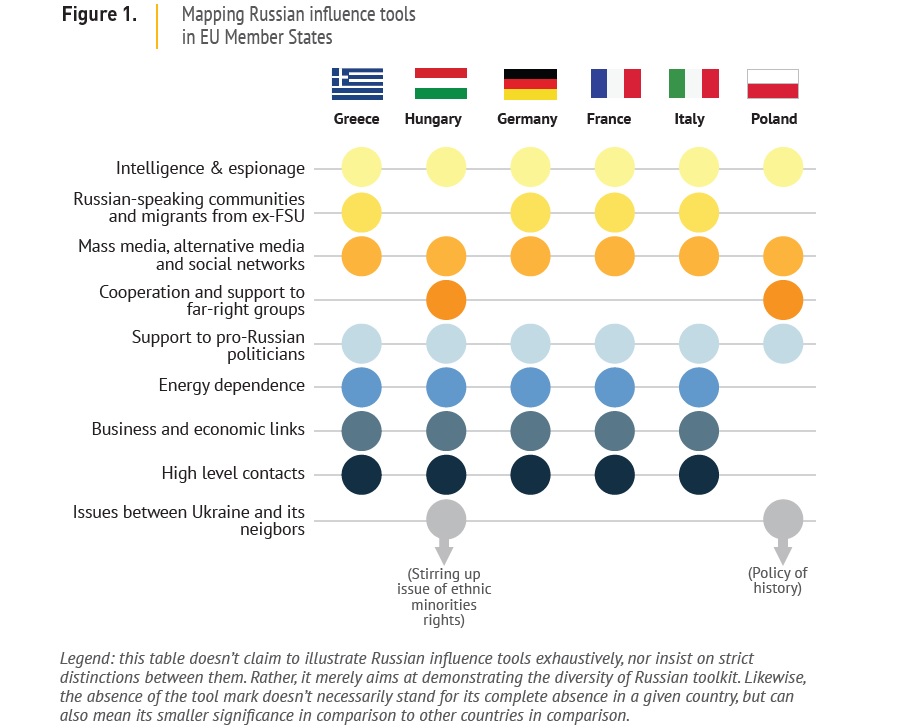

Russian tools of influence can be categorized as follows:

High-level contacts. Vladimir Putin makes a point of maintaining personal contacts at the highest level, be that with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Greek PM Alexis Tsipras, Hungarian leader Viktor Orban, Italian PM Giuseppe Conte and Deputy PM Matteo Salvini, or French President Emmanuel Macron. Putin likes to communicate his agenda himself: for example, when the Russian leader complained to Merkel about the supposed persecution of Russian journalists in Ukraine, she promised to raise this issue with the Ukrainian president.

Business and economic links. This is a powerful tool that converts those European businesses that cooperate with Russia into lobbyists for continuing cooperation. This instrument works best with the countries whose trade with Russia is relatively high, such as France, Germany and Italy. Still, even with those countries, Russian ranks 15th, 14th and 13th for imports from these countries, accounting for only 1.2%, 2% and 1.8% of their exports,[1] but since turnover is in the billions of euros, it still represents substantial leverage that Russia can use to pressure and blackmail, such as with its countersanctions on imports of EU food products. The Italian and French business lobbies are particularly notorious for pressuring their governments to lift sanctions, even when their trade is moderately or barely affected by Russia’s countersanctions. On the other hand, Russia can use the promise of economic aid as leverage in the case of weak economically countries like Greece. Russian capital also plays a substantial role in many European countries, through investments in commerce and in real estate. A classic example is Greek-Russian businessman and ex-Duma member Ivan Savvidis, a man close to Putin who owns real state, a football team, a hotel complex, a number of companies, a TV station and three newspapers, and a port in Thessaloniki.

Energy leverage. A specific aspect of business and economic leverage is the energy component, which Russia uses to great effect against EU and NATO member states. This leverage is twofold: cooperation and dependency. Examples of cooperation include investment in Gazprom’s controversial Nord Stream II project, Italy’s Saipen establishing a joint venture with Russia`s Novatek for LNG co-production, Italy’s Eni working with Rosneft, and many more. The downside, dependency, can even lead to blackmail: Italy receives 20% of its domestic oil needs and 45% of all the gas it consumes from Russia, leaving it vulnerable to an arbitrary “shut off.” The third way that energy leverage is applied is in the promotion of individual politicians. Russia offered Greece a gas discount in 2015, which would have allowed Athens to sustain its budget. In Hungary, Russia helped lift Viktor Orban’s ratings in 2011 by enabling him to secure a 21.4% government stake in Mol, a Hungarian oil company that used to be owned by Russia’s Surgutneftegaz. When Orban then lowered utility prices for Hungarians through some dubious schemes that involved cutting down gas purchases from Russia, Russia made no noise—in great contrast to what it did in many other countries, including Ukraine. Analysts say that the lower residential utility rates contributed to Orban’s victory in the 2014 election.

Being a pro-Russian politician can be a normal affair, as in Italy, or damaging to the reputation, as in Poland. However, Russia has consistently worked with various political forces

Support for pro-Russian politicians. Being a pro-Russian politician can be a normal affair, as in Italy, or damaging to the reputation, as in Poland. However, Russia has consistently worked with various political forces in every country, generally fairly popular or quite marginaler. These political forces include Germany’s Die Linke and AfD, whose Bundestag faction head Alexander Gauland has publicly justified the annexation of Crimea, while Die Linke members often visit Moscow and Ukraine’s occupied territories in the East. In Italy, Yedinaya Rossiya [United Russia] has established the links with the 5 Star Movement and Lega Nord —in 2013, it even established formal cooperation with Lega Nord, when the party only enjoyed marginal popularity. In 2014, France’s National Front received €11 million loan from a Moscow-based lender called the First Czech Russian bank and Jean Marie Le Pen, the founder of the National Front received a loan of €2 million from a Cypriot fund reportedly controlled by former KGB agent Yuri Kudimov. On France’s left, Russia has been providing more passive ideological support for Unsubmissive France, led by Jean-Luc Melenchon, a populist party peddling among others, withdrawal from NATO and even a “Frexit.”[2] In Greece, Russia supports the ultra-nationalist Golden Dawn party, which advocates explicitly pro-Russian and anti-American foreign, economic and energy policy.[3] In Poland, Russia relies on more marginal parties and movements, such as Kukiz 15 and the National Movement, as well as individual politicians like MEP Janusz Korwin-Mikke and the pseudo-party Zmiana, whose leader received money from Russia for pro-Russian activities,[4] was subsequently charged with espionage, and is currently on trial. In Hungary, one of the most notorious cases is currently also underway: the trial of ultra-nationalist Jobbik MEP Bela Kovacs, for allegedly providing Russia with intelligence.[5] In some cases, there is clear evidence of explicit financial support from the Kremlin to the parties in question, in others, there is only talk about political and ideological support.

Cooperation with and support for far-right groups. Far-right NGOs and associations are natural allies for Russia, because they advocate an anti-European and anti-liberal agenda. While Russia did not necessarily take part in their founding and may not have inspired all of their activities, they serve Russia’s interests well. They are particularly useful in Hungary and Poland: the Hungarian National Front (Magyar Nemzeti Arcvonal or MNA), whose leader was trained and Hídfő website controlled by Russia’s Chief Intelligence Directorate, the notorious GRU[6]. In Poland, it’s Falanga and the Camp of Great Poland (Oboz Wielkiej Polski). Among others, Falanga was involved in the burning down of the Hungarian culture center in Zakarpattia, intended as a provocation to damage Hungarian-Ukrainian relations.[7] Members of Falanga and OWP travel to and even live at times in occupied Donbas, hold rallies in Warsaw in support of Novorossiya, and so on.

In Poland and Hungary, such groups are used so stir up conflicts between Ukraine and its neighbors, while in Western Europe, the tactic is different. There, Russia has set up representative offices of the two pseudo-republics, DNR and LNR, in cities like Messina and Turin in Italy and Marseilles in France. Legally, these organizations are public associations, so it is not easy to close them down. More importantly, they were founded and are run by local nationals, which gives them some legitimacy in the eyes of the authorities and locals.

Disinformation through media. This is by far the most broadly used weapon in Russia’s hybrid war. Two types of media mediums are the most prominent: official Russian media channels, such as RT and Sputnik, and alternative media — a large number of niche right-wing websites that capitalize on conspiracy theories and an anti-European, anti-American and anti-liberal agenda. Russia invests significant resources in its international media campaigns, having spent €387 mn in 2017, which is considerably more than Deutsche Welle’s budget of €328mn. Russian media caters more to the Russian-speakers in the countries in question, who are often emigrants from the FSU, with Germany, France and, to a lesser extent, Greece, having a substantial community. In Italy, the governing parties rely on Sputnik and RT for information and arguments. In countries like Poland and Hungary, where Russian speakers are scare, “alternative” websites are more popular. For instance, the Polish conservative portal Kresy.pl has some 100,000 followers on Facebook, which is comparable to the audience of the leading Polish daily, Rzeczpospolita. Overall, the audience for questionable news and analysis outlet is smaller than that of established media, but cannot in any sense be dismissed. Social networks are also widely employed, with Italy being one of the prominent examples of twitter attacks in several situations, including the 2016 referendum campaign, the 2018 election campaign and formation of the new Cabinet in 2018, when thousands of tweets called for President Mattarella’s resignation.

Russia invests significant resources in its international media campaigns, having spent €387mn in 2017, which is considerably more than Deutsche Welle’s budget of €328mn

Intelligence and espionage. There have been several revealing cases of Russian intelligence recruiting spies among locals and infiltrating various organizations in Europe. The Hungarian National Front is a good example: its representatives were actually trained by the GRU. In Poland, an Energy Ministry official was charged with spying for Russia, gathering critical information for the Nord Stream II project.[8] There are also documented cases of Russian nationals who were engaged in covert intelligence activities being expelled from Poland, a well.[9] Germany has repeatedly accused Russia of cyberattacks on its state institutions. According to Emmanuel Macron’s staff, 2,000-3,000 attempts were made to hack his office during the presidential campaign in France. Poland reports cyberattacks from what seem to be Ukrainian servers, too, but attributes these attacks to Russian actions. In Greece, Russian diplomats have been accused of attempting to bribe Greek officials and clergy[10].

FSU migrants. Russian-speaking communities in Western Europe, where large numbers of former soviet nationals emigrated—in Germany alone, they are at least 3.5mn—have become agents upon whom Russia can rely for a number of purposes. Firstly, they are avid consumers of Russian propaganda and can influence both public discourse and voting patterns within their communities. However, they sometimes assume other, more sophisticated roles. For example, Kartina TV, a media company that broadcasts Russian channels in Germany and is owned by Transnistrian oligarch Viktor Hushan—known to be under investigation of the Security Bureau of Ukraine or SBU—, has broadcasted promovideos for AfD in Russian, and the party saw more support in the regions with more Russian speakers. Some locals were also employed in various kinds of street actions, such as protests over the “Lisa case,”[11] and protests organized by Oleg Muzyka, known for pro-Russian activities of a similar kind in Odesa in spring 2014. Russia also tends to use Russian speakers from the FSU to promote its concept of a “single nation,” with the supposedly German-Ukrainian Information and Culture Center in Düsseldorf promoting Russian propaganda and holding events with Die Linke MP Andrej Hunko—one of the most active Russia promoters in the Bundestag. In Italy, a Transnistrian Russian writer called Nikolai Lilin makes frequent media appearances.

Special cases. In almost every situation, there is some special context that allows Russia to employ additional tools. In case of Hungary and Poland, it’s controversial issues in bilateral relations with Ukraine, such as minority language protections and the approach to historical memory. Russia gains a major advantage in playing these countries off against each other and preventing them from supporting Ukraine’s European and Euroatlantic aspirations. For example, when the Hungarian-Ukrainian relations were aggravated by the Law on Education adopted by Ukraine in 2017. Russia used the situation to feed the narrative of Ukraine as an intolerant place. In the case of Poland, the narrative of Ukrainian “nationalism” also plays into Russian hands. Ukrainian sources report that 17 provocations against Poland, all traced to Russia, were prevented in Ukraine in 2017-2018 alone. The arson attempt on the Hungarian community building in Uzhhorod is now blamed on Falanga but it’s an apt illustration of the hybrid interference in relations among three neighboring countries. In the case of Germany, the Crimea-based ethnic German community is also being used by Russia to advocate the withdrawal of sanctions and recognition of the annexation of Crimea as legitimate, among others.[12]

4. BEST PRACTICES

The governments of EU countries have made many attempts to counter Russian influence in the EU. Some countries have been successful, offering good models for how to uncover and limit the Kremlin’s agenda and even stop its overt influence. Others have been less successful. The success stories can serve as best practice models for countries struggling to prevent external influence and to follow an independent policy.

The disruptiveness of Russia’s policy has been noted, tracked and limited to varying degrees in France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Greece, and Hungary. Paris was among the first capitals to put forward a policy of rolling-back Moscow’s disruptive influence. One of the game-changers in French politics was the 2017 parliamentary election. Most of the French politicians who had a long history with Russia did not make it into the Assembly and most of them were from the Republican Party. This really altered the political landscape after election, costing Russian about 80% of its influence with the MPs who supported Moscow in specific situations, and 35% in the Senate.

Media and social media

In the end, the campaign against Emmanuel Macron orchestrated by Russian media during the presidential election proved self-defeating. First, after multiple propaganda materials appeared that denigrated him, Macron simply removed access to RT and Sputnik at his campaign headquarters. He accused the two Russian sources of spreading lies, including allegations of an extramarital relationship with a man. Once he was elected president, Macron surprised the entire world by denouncing RT and Sputnik as “liars” and “agents of propaganda” during a joint press conference with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Macron’s statement went viral and the image of Russian media, which was already suffering, has damaged even more. Although it was quite determined to antagonize Emmanuel Macron, Russia could not have anticipated this enormous shift.

The campaign against Emmanuel Macron orchestrated by Russian media during the presidential election proved self-defeating

Still, RT and Sputnik continued to distort news and spread disinformation, so the French authorities began to respond. First, the outlets were warned several times about the fake news they presented to the French public. RT is facing similar issues in Germany, the UK and the US. But France’s mechanisms against fake news have moved way ahead. On July 4, 2018, French lawmakers adopted legislation that allows judges to remove or block media content that is deemed to be false. The law also allows candidates running for office to appeal to the courts to stop the dissemination of false information in the 90 days before an election.

The idea of such a law was initiated by President Macron because he believed that foreign media have tried to interfere in the elections in France. During heated debates in the National Assembly, which lasted well into the night, there was also opposition to the bill. Some MPs felt that the anti-fake news bill was walking a fine line between freedom of speech and censorship, and expressed concern about potential infringements on freedom of expression. Others, like leftist Jean-Luc Melenchon, denounced the bill, calling it a targeted bill meant to specifically ban RT and Sputnik.[13] Following the debates in the National Assembly, the Senate rejected the bill few weeks later. If the two chambers are unable to come up with a joint vision, priority will be given to the National Assembly, where Macron’s party has a majority.[14] Of course, the bill could be still challenged in the Constitutional Court, but regardless of the specific outcome, the trend towards exercising control over foreign influence on elections will continue in France.

The French bill also allows the government to force social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook to become fully transparent and, if necessary, to disclose the source of sponsored content on their platforms, in order to counter efforts by foreign-funded organizations to destabilize the country politically.[15] In fact, French social-media platforms have already had experience regarding election campaigns. Facebook stated publicly that it had suspended about 30,000 accounts for promoting propaganda and election-related spam; later the number rose to more than 70,000.[16]

Successful examples of countering Russian influence in various media can be also found in Germany. German print media, for the most part, and think-tanks have proved resistant to Russia’s subversive operations and showed that they uphold the principles of international law, indicating, indirectly, support for Ukraine’s position.

Facebook stated publicly that it had suspended about 30,000 accounts for promoting propaganda and election-related spam. Later the number rose to more than 70,000

The peak of Russia’s subversive efforts in Germany was the “Lisa case,” where a 13 year-old ethnic Russian girl named Lisa supposedly disappeared from her family home in Berlin in January 2016. Riding the wave of anti-migrant sentiments, the fake story of the rape of a minor by Arab migrants was designed to rile ordinary Germans into widespread protests and was clearly aimed at weakening Chancellor Angela Merkel. The “Lisa case” failed when Germany’s law enforcement agencies immediately investigated, domestic media covered the incident in a highly professional manner work, calmly covering events without resorting to the hysterical manipulations typical to Russian media and even German “alternative” media, which tend to mesh with Russian positions. One example is Kompakt, a magazine that publishes right-wing radical and Islamophobic materials.

Additional vigilance to disinformation and subversive activities could be found among state institutions in Poland, where media outlets were blocked or denied licenses for violating the law. For example, the Facebook page “Ukrainiec NIE jest moim bratem” (Ukrainians are not my brothers), which was spreading hate speech against Ukrainians, was blocked for a month. Another example a local radio station that lost its license for renting airtime to Russia’s Sputnik,[17] a state-run propaganda outlet.

Suspending the licenses of Russian media also came up in France when a group of French experts on Russia signed an open letter, calling on the Audiovisual Council to suspend the broadcast license for RT for “sowing discord and weakening democracies.”[18] Although the license was not suspended, appeals like that put pressure on French authorities to be vigilant about the activity of RT in France and act against disinformation. Interestingly, RT put together an ethics committee, as required the French law, but the committee was clearly biased, since, in addition to diplomat Anne Gazeau-Secret, journalists Jacques-Marie Bourget and Majed Nehmé, and Radio France ex-president Jean-Luc Hees, it included Thierry Mariani, a former senator and one of the most vocal supporters of Vladimir Putin. If RT’s license is not suspended after it presents disinformation, there should be a demand that the channel establish an independent, impartial committee.

The resistance of French journalists to propaganda also merits praise. Le Monde’s Decodex project was aimed at fact-checking products based on a large database to identify unreliable information and manipulation. Journalists in Germany also demonstrated a very responsible approach, especially with the “Lisa case,” as did journalists in Poland. Among Italian media, high-quality unbiased materials appear in print media such as La Stampa, La Reppublica and Il Corriere della Sera. For example, La Stampa published its own investigation over the use of Twitter accounts in Italy in relation to the 2016 referendum, based on which an Italian court opened proceedings to investigate external influence.[19]

In Italy, Sputnik and RT are also available, but unlike France and Germany, Italians tend to trust Russian media. The Spanish newspaper El Pais found that Sputnik and RT had a definite impact on the spread of anti-immigration discourse on the eve of the elections in Italy. El Pais processed more than 1 million posts from 98,000 social media accounts and found that 90% of the content distributed by Sputnik and RT came from anti-migrant activists and organizations. While anti-migrant sentiment has broad roots, it seems clear that Russian media has contributed to the radicalization of anti-migration discourse in Italy, which, in turn, favored Lega Nord and its leader Matteo Salvini, known for his ultra-right views on migration.

Sanctions and international support

Supranational instruments are also in a position to identify and isolate Russian efforts. Although the EU as an institution doesn`t play a leading role in fighting Moscow’s disruptive activity, Brussels continues to offer the necessary platform to align all EU members, provides technical advice while drafting and implementing sanctions, and enforces a common position that is difficult for any individual EU country to abandon.

The same is true of NATO, which involves a high level of ongoing interaction among members and provides for tools to sideline Russian interference. In sanctions policy, Germany played an important role and adopted a principled position that sanctions could be lifted only after the full implementation of the Minsk accords. Berlin not only demonstrated its resilience to the destructive effects of Russia in its country, but also managed to maintain unity within the European Union at critical points, in particular with regard to sanctions policy.

Germans are not always sympathetic to the positive remarks of Berlin issues regarding sanctions against Russia. There were moments when, without the personal intervention of Angela Merkel, the introduction or continuation of restrictive measures might have been questioned. Some German experts insist that it is better to focus on European solidarity in general, and not on the coercive policies of a single country, saying this delegitimizes the notion of a common policy, by making it seem like it’s all about Germany—whose reputation has already been damaged in recent years, especially in southern Europe.

However, Germany’s role should not be diminished, either: probably no other country has as much weight and political will to maintain the unity of the EU in response to Russia’s subversive actions. Moscow was confident that western governments would not respect sanctions, as had happened with the war against Georgia in 2008. But, as German politicians and experts often point out, the EU continues sanctions, despite attempts to bury them almost the next day after they are adopted. Chancellor Merkel personally played a role in securing unity and this success has deterred Russia from escalation—so far.

Chancellor Merkel personally played a role in securing unity and this success has deterred Russia from escalation — so far

The success of sanctions against Russia has also another dimension, which is less known and also not at all a practice to follow. In recent years, EU countries have fallen victims to Russian cyber-warfare. In 2007, Estonia’s financial, media and government websites were among the first victims of Russian cyber-attacks. These were followed by attacks on the German Bundestag, French media and the campaign headquarters of Emmanuel Macron. Today, many EU countries have strengthened their capacity to fight cyber-attacks. Indeed, NATO set up a Cyber Defense Center of Excellence one year after the attack in Estonia. The EU wanted to impose sanctions on states that carry out cyber attacks to deter them, especially Russia. However, Italy opposed the idea and the measures were not adopted by the EU.[20]

Expulsion of diplomats

One widespread practice to counter the Kremlin’s subversive activities is the expulsion of Russian diplomats, including those involved in unfriendly actions and threats to national security towards the host country. The best-known case of mass expulsions was related to Skripal case in Great Britain, when over 150 Russian diplomats were expelled worldwide in a show of solidarity with London.

Greece decided not to expel any Russian diplomats in March 2018, but in July, Athens expelled two. The Greek foreign minister explained that the measure was intended to prevent foreign interference in the internal affairs of the country: Greece accused the Russians of attempting to bribe Greek civil servants and church members The FM noted: “Obviously, some Russians believe that they can work in Greece and not respect its laws and procedures. However, this kind of attitude is unacceptable for Greco-Russian relations.”[21] So, for Greece, the expulsion was a preventive measure, rather than a demonstrative attempt to break long-term relations between the two countries by openly condemning Russia for trying to prevent the conclusion of an agreement with Macedonia (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, FYROM) to change that country’s official name.

Spy scandals

Unlike Athens, Budapest expelled one diplomat in April in solidarity with London over the Salisbury novichok attack. In fact, the Russian diplomat had been engaged in illegal intelligence-gathering in Hungary and was due to be expelled anyway: the Skripal case offered a useful opportunity. Back in October 2016, the Hungarian government was carrying out an investigation that involved a search in the home of neo-nazi Istvan Gyorkos, who headed the right-wing armed group of the Hungarian National Front. Gyorkos’ arrest proved dangerous, as one Hungarian policeman was killed when the suspect opened fire. Hungarian journalists managed to find out that officials from the Russia’s chief intelligence agency, GRU, had been in contact with Gyorkos and had provided him with military training. As it turned out, the GRU officers had actually worked at the Russian embassy in Budapest under diplomatic cover.

The Gyorkos case is not the only one, nor even the most important one. Hungarian MEP Bela Kovacs was revealed to have been spying for Russian intelligence. The Hungarian prosecutor’s office accused him of espionage in 2014 and his immunity was lifted by the European Parliament. No other country, despite numerous scandals over Russia’s intervention such as in the US and French elections, had exposed such a high-level politician. The Hungarian expert community noted that Kovacs’s exposure would affect other politicians, if nothing else, to be more cautious in their relations with Russian special services. At best, it should lead to the end of any suspicious collaboration at all. Still, the majority of Hungarian experts said the Kovacs case was concluded because of political expedience and the determination of Hungary’s leadership to reduce the popularity of the right-wing Jobbik Party.

One of the best practice models was the shutting down of an organization that was recruiting Italians to fight in the Donbas

As in-depth country reports indicate, the counter intelligence efforts of EU member states have handled many other cases. Possibly the most successful action was by Italian law-enforcement agencies—and one that could be considered the best practice model—was the shutting down of an organization that was recruiting Italians to fight in the Donbas. The Italian police uncovered the scheme and stopped the sending of Italians to fight in illegal armed groups. Based on information from the Ukrainian embassy in mid-April, about 30 Italians who, according to the Italian government, had fought in the Donbas, the Genoa Public Prosecutors Office launched a case over the unlawful participation of Italians in hostilities in third countries. As a result of an investigation by BuzzFeed News, the head of the Lombardy-Russia Association, Gianluca Savoini, who is also a close advisor of Salvini, was linked to the suspects in this case.[22]

Of the six countries, the first to warn about the threat of Russian subversion was Poland. Its Internal Security Agency (ABW) issued a report back in 2014 warning about the activity of Russian intelligence in Poland and identified Russia’s objective as distorting public opinion about the conflict in Ukraine and damaging Ukrainian-Polish relations by stirring up historical wounds. After the start of Russian aggression, the Polish public and the Polish authorities reacted strongly to Russia’s actions: by 2015, 81% of Poles were negative about Russia,[23] and the Year of Poland in Russia was also cancelled that year.

The highest profile operation by ABW in recent years was the arrest of Mateusz Piskorski, leader of the pseudo-party, Zmiana, which was nicknamed “Laundergate.” Piskorski has been in custody since 2016, on suspicion of espionage on behalf of Russia and China.[24] Previously, Piskorski was an MP in the Polish Sejm and was known for his lengthy ties with Russia and his “electoral tourism:” organizing delegations of European politicians to observe elections in unrecognized territories—Transnistria, Abkhazia and South Ossetia—and in countries that were of strategic interest to Russia, such as Syria, Libya. In 2014, Piskorski was an “observer” at the illegal “referendum” in Crimea.

Another espionage case involved an official at the Polish Ministry of Energy. Mark W. was handling in strategic projects in energy infrastructure and receiving EU funds for a program aimed at diversifying gas supplies away from Russia. Polish authorities discovered, however, that the official was transmitting information about Polish government`s decisions around the construction of Nord Stream II and about “important investments in Poland’s interests”[25] to Russian intelligence agencies. After his arrest, Poland expelled four Russian diplomats, which coincided with the widespread expulsion of Russian diplomats by western countries in response to the Skripal poisoning. In another case, a Russian woman by the name of Ekaterina Tsivilskaya was deported from Poland for “attempts to consolidate pro-Russian circles in Poland around two priority objectives for the Russian side, namely, stirring Polish-Ukrainian enmity in the social and political spheres, and infiltrating Polish historical policy with her Russian narrative.”[26]

Insulation from religious influence

Aside from espionage, changes took place in Greece after Russian attempts to influence Greek policy with regard to the name agreement with FYROM. Moscow used the church as a tool of soft power and Russian influence on Mount Athos was undeniable. Decisions made by the Greek Orthodox Church shortly after the expulsion of the Russian diplomats were clearly influenced by the Greek government. In early August, the Holy Synod of the Greek Church amended the statutes of the Church Administration, withdrawing the autonomous status of monasteries. From now on, all monasteries are really, not just nominally, subject to a certain metropolitan. Moreover, monastery officials are no longer allowed to make political statements on their own that promote ideas beneficial to Russia in Greek society, the church traditionally is seen as a higher authority than the government itself.[27]

Certain changes in the administration also took place at Mount Athos. One reason why the Russian diplomats were expelled from Greece was that their officials had been trying to increase influence over the monastery. On August 13, the Greek government appointed a new governor of the Holy Mountain, Kostas Dimas, who was proposed by PM Tsipras and approved by Ieronymos II. Prior to this, Dimas was a personal advisor to Ieronymos II, Archbishop of Athens and all of Greece, and also served as general director of the Apostoli Charity of the Athens Archdiocese of the Greek Orthodox Church.[28] In other words, in the context of conflict between Russia and Greece, the changes can be seen as measures taken by the Greek Church and government to strengthen control over the activities of the church and avoid unwanted outside—in this case, Russian—influence.

The changes can be seen as measures taken by the Greek Church and government to strengthen control over the activities of the church and avoid unwanted outside—in this case, Russian—influence

All these examples of countering Russian influence, interference and subversive activities present a rich, diverse and effective set of best practices that has already been tried and tested. Such best practice can and should be taken to heart by all affected countries, starting with discussions at various levels, including bilateral, EU and interagency levels. EU countries are much stronger when they cooperate against a common threat. The recent case of the Austrian officer accused of spying for Russia for two decades was exposed by the British, who had plenty of challenges lately, curbing Russian interference, especially after the Skripal case. These positive examples validate the strategy of joint operations and exchanges of best practices.

5. ULNERABILITIES OF RUSSIAN INSTRUMENTS

As the previous section highlighted, Russia uses instruments that are multi-layered and diverse. At the same time, many of them are vulnerable, often controversial and even self-defeating. The structural vulnerabilities of Russian instruments can be assigned into the following conventional categories:

1. No mainstream policy. Russia’s propaganda instruments are mostly aimed at people, organizations and political parties whose main agenda is to criticize the system: far-right and far-left political movements, supporters of conspiracy theories, and populists. In France, this is a structural failure, since the bulk of French public opinion supports political parties that are not trying to change the system of governance, just to improve it. This dates back to the beginning of the Fifth Republic in 1958, even if the last presidential election showed a distinct move towards the center. In that context, it is questionable whether real and sustainable successes can be achieved by Russia’s information strategy, apart from disturbing the public debate at its margins.[29] Some will say that stirring up dissatisfaction in French society is also a result, however the national popular movements are promoting people devoted to the interests of France and Germany. The picture is similar in other countries that we studied in depth for this report. Russian policy was to create dissatisfaction and resentment with the broader political agenda. An exception could be countries that are seen as more conciliatory towards Russia, like Italy and Hungary, even if Russian policy in these countries was intended to cause ruptures when it was about, for instance, the EU.

2. Contradictory vessels. The two main vessels for Russia’s information strategy are far-left and far-right parties. In Germany, the AfD is seen as the main party echoing the Russian narrative on a number of issues and it is suspected of having support from Russia. Influential German MP Omid Nouripour noted: “AfD is an extension of Putin’s arm in the German legislature.”[30] And if AfD is populist, a fierce critic of migration and the EU, then Die Linke, on the left, is anti-American with a moderate position on the LGBT agenda and migration. Some of its members have publicly advocated for recognizing Crimea as part of Russia.[31] In France, the National Front’s ties with the Kremlin are well known—loans from Russian banks, Le Pen’s visits to Moscow ahead the French presidential election—, and this has proved to be more of a burden than a benefit. At the same time, Unsubmissive France has not formalized its ties with Russia, for now: during his 2018 trip to Moscow, Jean-Luc Melenchon was apparently not received by any Kremlin officials. As with Germany, if far-left supporters can be seduced by the Kremlin’s anti-American rhetoric, they are uncomfortable with anti-LGBT or anti-migrant propaganda. Put into a historical perspective, during the Soviet Union, Moscow relied on the French communist party and its affiliated movements in France. Now, it has to deal with recipients that are competing against each other in the political arena, which seriously hampers the effectiveness of Russia’s information strategy in France.[32] Broadly, this formula applies to other countries.

3. Lack of credibility. Russia’s information strategy relies heavily on fake news. However, when fake news refers to topics like Syria or Ukraine, it does not really affect public debate in countries like France, aside from some marginal groups—because most people are simply not interested. But when the fake news is about the countries themselves, it usually causes more damage to Russia’s information strategy. On several occasions, mainstream media in key EU countries targeted by the Russian propaganda denounced RT and Sputnik articles that were providing biased coverage of the real situation, whether German, Italian or French media.[33] For instance, at the beginning of April 2017, Le Monde published an article on opinion polls during election campaign, criticizing a dubious poll that put François Fillon at the head of the candidates and reposted by Sputnik.[34] Another example is the Lisa case in Germany, when Russia actually exposed itself as a bearer of lies and lost some public support.

Russia has also tried to use other fears and prejudices in German society to advance its own agenda. For example, Russian propaganda attempted to raise the narrative of “past merits,” for which Berlin should now pay tribute. One of the arguments with German audiences was: “Russia contributed to the reunification of Germany, so it’s strange that the Germans do not approve of the reunification of Russia and Crimea.” For the most part, Germans did not fall for such manipulations: the reunification of Germany did not go against international law, in contrast to the annexation of Crimea, which violated numerous bilateral Ukrainian-Russian and multilateral treaties.

In Hungary, the credibility and soft-power of the Russian narrative is also hampered by several factors. First, Hungary is not a Slavic country, eliminating an argument Russia often uses in Bulgaria, Serbia, and Belarus. Secondly, there is no large Russian ethnic community that would justify Russia’s claim a role in domestic politics. And thirdly, historical circumstances—the soviet period—affect Hungarian public opinion and predispose ordinary Hungarians to be cautious about present-day Russia.

4. The ill-repute of pro-Russian politicians. Where in Italy, Moscow won the jackpot with Matteo Salvini, in France it keeps betting on the wrong horse. The story of François Fillon is a good lesson. While campaigning, Fillon was accused of mismanaging funds by paying his wife for a job she never did. The fact is, that most politicians on whom Russian bets have issues with their reputations: Le Pen, for instance, claimed €300,000 for a parliamentary assistant. Clearly, potential financial “benefits” have guided the pro-Russian feelings of some French politicians—and not only. This is a weak spot for Russia. Decent politicians who are true patriots of their country have far less chances of being Russia’s favorites. Since Russia’s preferred candidates often have issues with the law, and with ethics in general, this should be kept in mind.

While in Italy Moscow hit the nail on the head with Matteo Salvini, in France it was always bidding on the “wrong” person

Moreover, French elections tend not to really focus on international issues, but more on local issues, where the protest vote is very strong. Russians themselves did not want Le Pen to win the elections since they understood that her presidency would be impossible to navigate. However, she did a good job of weakening France. Russians tried to promote François Fillon as the main “Russian” candidate.

5. Lack of public support. Nearly 60% of Germans do not consider Russia a reliable partner, which is a decent of hedge against Russian provocations.[35] The same poll conducted in May 2018 shows that most Germans favor sanctions against Russia, with 45% favoring the current level of sanctions and 14% wanting them stronger. Only 36% want to see the sanctions softened. However, there were 10% fewer of those who advocated for stronger sanctions: in 2016 24% did and last may only 14% did.

Hungarian society is also very cautious towards Russia, mainly for historical reasons. Nearly half of the Hungarians, 48%, disagree with Vladimir Putin’s policies, while 33% agree.[36] What’s more, 76% of Hungarians would vote in a referendum for NATO membership, and 75% for EU membership.[37]

A 2017 Gallup poll show the approval rates of Putin across the researched countries. In Poland, only 9% approve his policies and 85% are against, making Poland the country where Putin has the lowest approval. In Germany, 20% approve him and 74% are against. France is close to Germany, with 18% in favor and 64% against. Italy offers more approval for Putin, with 35% in favor, but a majority, 52%, nevertheless against. Of the six researched countries, the only one positive on Putin is Greece, which has 72% in favor and 25% against. However, scholars in Greece suggest that these proportions may have changed, especially after Russia’s unfriendly actions in summer 2018.

6. Little influence with key political figures. Russia’s influence on key political figures is either limited or absent. A story from Germany is quite telling: pro-Russian Matthias Platzeck, chair of the German-Russian Forum, spoke recently in a conciliatory tone about Moscow, calling on Berlin to start a new partnership with Russia, without any preconditions.[38] In one forum, Platzeck actually apologized to Russia for the way the West was ignoring it as a regional power. The Russians, instead of admitting their mistakes, began to insist that there had been no annexation of Crimea and no aggression against Ukraine. German observers note that this actually frustrates those who favor dialogue with Russia—because Russia is not ready for it.[39] German politicians who are sympathetic to Russia are not able to advocate for Putin, especially on issues like democracy and human rights, which is a major weakness of Russian influence in Germany.

Italy might be the exception, given Matteo Salvini’s open support for Russia and his fascination with Putin. However, even if Lega Nord is overtly pro-Russian, their coalition partner, the 5-Star Movement, is more ambivalent and, despite a certain propensity towards Russia, has not yet formed its foreign policy agenda. Among others, the members of this party lack political and foreign policy experience, not to mention knowledge of the region. On one hand, this makes them an easy target for the Russian narrative, but on the other, they are still open to alternative positions.

In Poland, there are certain groups of Polish politicians with clearly anti-Ukrainian sentiments, but this has not made them pro-Russian. In Polish political circles, there is a consensus on Russia, and today no serious Polish politician speaks about rapprochement with Moscow. Evidence of Warsaw’s solidarity with Kyiv was demonstrated in a 410 out of 460 vote in the Polish Sejm in favor of a declaration calling for the release of Ukrainian filmmaker Oleh Sentsov and other political prisoners in the summer of 2018.

All the experts surveyed in this study unanimously stated that Russia had no serious ties with their ruling party. This is not so much because of Law & Justice’s (PiS) anti-Russian position, as because of the toxicity of showing support for Russia: ties to Russia are considered a major disadvantage for Polish politicians and only marginal politicians and public figures show any support for Moscow. For the same reason, there are no popular opinion leaders in Poland who advocate a pro-Russian position.

7. Religious influence. With Russia’s influence through religious ties, the first country that comes up—and the only one of the six studied—is Greece. Russia’s attempts to use the religious factor to influence domestic and foreign policy in Greece failed, among others, due to the very different nature of relations between church and state in Greece and in Russia, despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of the population in both countries is affiliated to the same, orthodox, church. Both in Greece and Russia, the church is close to the state. However, in Greece this proximity is enshrined in the Constitution—even though the Archbishop of Athens tends to follow the decisions of the Ecumenical Patriarch, rather than the interests of official Athens—, and the overwhelming majority of the population is sincerely religious. In Russia the situation is completely different: the church is officially separated from the state and the ordinary Russians are not especially religious and do not particularly appeal to religious orders. In fact, however, the Russian church is very closely connected to the state, and has been so for much of its history. And so, there is no particular religious affinity between the Greeks and the Russians.

Russia’s attempts to use the religious aspect in its influence on Greek domestic politics failed, among others, due to the distinctive nature of the relations between the church and the state in Greece and in Russia

In addition, Archbishop Ieronymos II of Athens subordinates himself entirely to the policies of Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, a fact that is especially relevant in light of the current confrontation between Istanbul and Moscow. In December 2017, a summit was held in Moscow to commemorate the centenary of the restoration of the Russian Patriarchate after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. About 380 Orthodox bishops from all over the world came to Moscow, including leaders of the Churches of Alexandria, Jerusalem, Cyprus and Albania—a total of 12 delegations. In this way, Kirill, with the support of Putin, implicitly but unambiguously demonstrated to Bartholomew, that he could be an alternative to the “first among equals” of the Orthodox world. Only two church leaders were absent among the canonical Orthodox churches in Moscow: the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and the Archbishop of Athens Ieronymos II. The absence of Bartholomew in Moscow was interpreted as a response to Kirill’s failure to visit the All-Orthodox summit on Crete in 2016. Ieronymos II was also absent, unwilling to break the allied relationship between their Churches and act contrary to Constantinople. Despite the fact that the Church in Greece is a state structure, it still falls under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch, so the foreign policy actions of Ieronymos are in line with Constantinople, rather than in line with Athens.

8. Strong allies, institutions and values. Transatlantic unity, including through NATO, is one of the key instruments in rolling back Russia’s malign influence, despite the fact that relations have suffered some shakeups lately, due to differences in visions between leaders in Europe and Washington. There are several examples that could illustrate weaknesses available to Russian manipulation in influencing EU leaders.

Even if the Nord Stream II pipeline looks like a political victory for Russia, there is another side of the medal that merits additional attention. The influence of the United States in deterring Russia’s subversive actions cannot be underestimated. Given that the construction of the Nord Stream II is seen as an essential security factor for future needs, including political purposes, America’s role looks like a “sort of” success story—“sort of” because of a possible ambiguous impact.

Germany is aware of the high probability of the United States imposing sanctions against companies participating in the Nord Stream II project. On the one hand, Berlin points out that the Trump Administration will rescue German politicians from the discrediting effect associated with the Russian pipeline. Angela Merkel apparently did not dare to criticize Nord Stream II previously in order not to jeopardize her coalition with the Social Democrats during the election campaign. For the German establishment, however, it is becoming increasingly difficult to justify the pipeline, to the press and other allies in the West, as a purely commercial project. This means that American sanctions would deprive the German political class of the headache given to them by Vladimir Putin. On the other hand, Germans, both the government and the non-government sectors, emphasize the extremely negative consequences of possible sanctions by the United States. This could well strengthen anti-American sentiment in Germany, potentially affecting cooperation between Berlin and Washington in supporting Ukraine. German observers criticized the possible placing of sanctions against the companies taking part in the construction of Nord Stream II, noting that such sanctions would be unhelpful, both for the transatlantic partnership in general and for western support of Ukraine in particular.

The Euro-Atlantic community and the US are also an anchor for Italian politics. Traditionally, Italy’s foreign policy was based on three pillars: European integration, Euro-Atlantic integration and the Mediterranean region. Accordingly, Russia was important to Italy, but not a priority partner, and European unity, despite some inconvenience to Italy, was a priority over Russia’s wishes. In the previous legislature, the removal of sanctions against Russia was put to the vote 11 times and never once passed.

With Italy, the role of the Italian justice and law enforcement systems also means a lot. One example is the shocking court ruling that requires Salvini’s party to return €49mn to the state budget—money the party received from the state and misused over 2008-2010. The Genoa Public Prosecutor’s Office has obliged Lega Nord to pay €600,000 to the state budget every year until the embezzled amount is fully reimbursed.

There are other vulnerabilities that are not structural, but still offer occasional opportunities for Ukraine.

Russia has made an enormous effort in uniting its diaspora and it has been partly successful. Still, Moscow has not been able to co-opt those who consider themselves victims of the Soviet Union or Putin’s regime. The political hardening of the Kremlin has helped to structure opposition movements within the Russian diaspora, as well.[40] For instance in France, the Russian diaspora is divided. Most of them are supportive of the Russian regime, but some 10-15% are against Moscow and are very active in getting their message out.[41] The existence of an opposition within the Russian diaspora is even more precious since the message passed by Russian immigrants is more credible than the messages of other actors who oppose Russia. The same can be seen in other countries where Russian immigrants mostly support the regime, but there are those who vociferously do not.

6. POTENTIAL VULNERABILITIES IN EU COUNTRIES

The main vulnerability facing countries in the European Union, when Russia can take advantage of its anti-Ukrainian policies, is the lack of unity among members regarding a response to actions by Russia that are in violation of international law. What’s more, Moscow uses not only any differences at the EU level or at the transatlantic level, meaning disputes between the Europeans and Americans, but also political competition within individual countries. There has been some success in countering this interference to at least partly neutralize vulnerabilities, but sometimes it’s hard to say exactly why Russia’s provocation in a given country failed: was it because the country resisted sufficiently or because Russia simply didn’t do a “good” job.

Russia will, most likely, continue to use five main vulnerabilities in EU countries for its anti-Ukrainian activities:

- political squabbles among political elites within EU countries and debates among EU member countries;

- the idea that sanctions damage EU economies;

- three main narratives to discredit Ukraine:

- Ukraine is not living up to EU expectations because it has failed to overcome corruption;

- Ukraine poses a threat to liberal values because it is promoting a nationalist line;

- Ukraine keeps violating the Minsk Accords and undermining continental stability.

- cyber security;

- Russian-speaking communities.

With the upcoming electoral season in 2019, it should be expected that Russia will increase its efforts to undermine Ukraine in all of these ways. The more the electoral process can be discredited in Ukraine, the weaker EU support will be for Ukraine’s political establishment after the presidential and Verkhovna Rada elections, and the greater the leverage Russia will gain.

VULNERABILITY #1. Helping elect politicians who threaten the cohesion of the EU

Next year brings elections to the European Parliament. This is a key battlefield for Russia in the upcoming months. If rightwing populists strengthen their positions, this will mean they will get stronger at the national level as well. Western democracies in general and EU countries in particular are especially vulnerable to information campaigns whose aim is to disrupt the political order in those countries by supporting radical movements and parties. Thus, in Germany Russia was not shy about its sympathy towards Alternative for Germany (AfD), which is a strictly right-radical party that is harshly critical of the current government’s immigration policies. In France, Moscow openly supported the radical right wing politician Marine Le Pen in the 2017 presidential election. A deepening crisis within the EU—Brexit and the migration cataclysm—provides fertile ground for the widespread narratives threatening liberal political forces that are widely disseminated by Russia’s international broadcasters as well. Moreover, the Russian Federation’s undermining impact in supporting radical populism is not always obvious. The problems within EU member countries themselves have fostered growing xenophobia and nationalism, where the interests of their own country override the interests of the Union as a whole. The election of politicians of this type threatens the continuing solidarity of the EU. Earlier, Greece worried the Union with the coming to power of Alexis Tsipras. In 2018, the baton passed on to Italy.

For now, there is a certain immunity among most EU countries against the coming to power of politicians who want to reconsider sanctions policies. The exception is Italy, whose calls to reconsider the automatic prolongation of restrictions against Russia could lead to a domino effect.

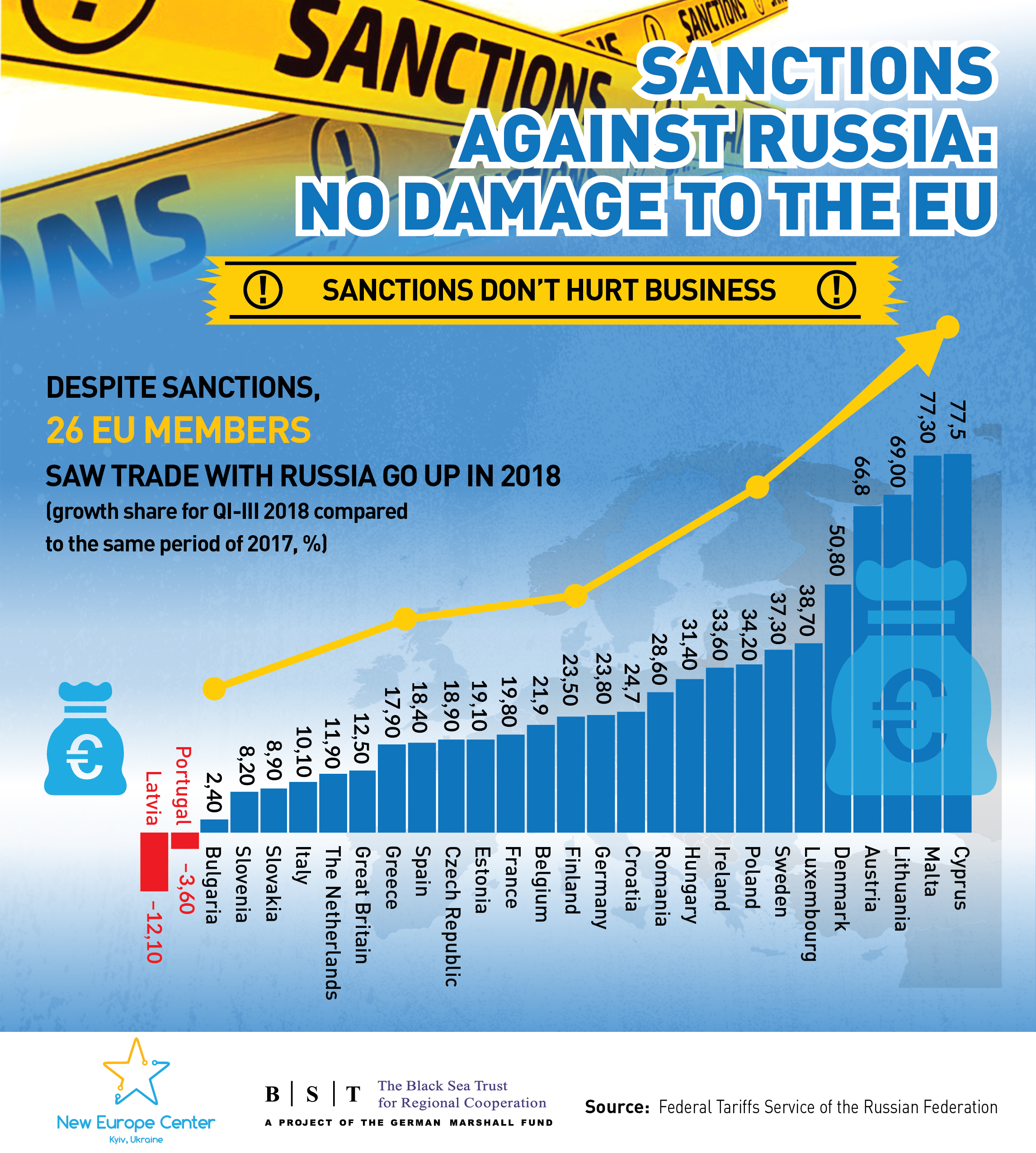

VULNERABILITY #2. Using businesses to pressure EU governments to change sanctions policy

Business is one sphere through which Russia will continue to win European hearts and minds. Those who are against sanctions think that the shortest path to European hearts lies through their pockets, so their main bet will be on the financial logic of various governments of EU countries and their voters. Trade turnover with Russia has been growing in majority of EU countries. Volumes are still far from their pre-war levels, but the positive trend is unmistakable (see Infographics 1). For instance, Russian exports to France returned to pre-war levels already in 2017, almost €6 billion. Russians have been using a very powerful argument in their dialog with EU business: “You could make more if the sanctions were dropped.” Evidence that companies in some EU countries have managed to reorient themselves on other markets don’t always sound convincing to audiences in other countries. Arguments that their companies could make even more profit if the Russian market weren’t closed are very effective. It’s not always easy to find understanding even when people point out that Russia’s market has been in crisis even without the sanctions.

The mercantile logic of those who oppose sanctions seems quite persuasive to many ordinary voters in the European Union. Ordinary Germans especially those living in provinces whose enterprises were linked to Russian ones, see the lack of jobs and declining incomes as the result of Berlin’s severe policy towards Moscow. This is especially true in the energy sector. And so Germany is not inclined to see a security threat in the building of the costly and large Nord Stream II pipeline: a German company is one of the investors in this Russian enterprise. Ex-Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who went straight to a high-level position at GazProm after leaving office, is the highest-profile representative of business and has been doing everything in his power to get Berlin to reconsider its position on sanctions. To a large extent the Hungarian government is also quite dependent on Russia, especially since it was helped in getting a €10bn loan to build a new reactor at its Paks AES. The Hungarian government has made the obligatory statements that EU sanctions against Russia should not be automatically prolonged. In both the German and Hungarian governments, officials are highly offended when they are accused of being pro-Russian in their policy positions. Berlin insists that its government cannot meddle in commercial affairs. Budapest also insists that its policies are not pro-Russian but pro-Hungarian, and that the convergence of Hungarian interests with Russian ones is mere coincidence. This confirms that government officials in most EU countries are fairly sensitive about any accusations of cooperating with Moscow, and tend to disavow similar information the minute it appears in the press. Moreover, German analysts point out that Germany is an example of how business, despite dissatisfaction, has been forced to adapt to national policy. Italy’s business lobby is a key player in a campaign in Italy to soften or withdraw sanctions altogether.

From time to time, the notion that Ukraine might become a new market for EU businesses is raised by Ukrainians, but this idea so far has not met with broad support in the business circles of other countries. By contrast, some 5,000 German companies operate in Russia today, employing over 270,000 and boasting a total turnover of more than €50bn. And these numbers are down since Russia attacked Ukraine: in 2013, there were over 6,000 German companies operating there. Clearly the decline is anything but catastrophic, as mostly it was SMEs that left the market because they couldn’t protect their capital investments. The presence of Big Business allows Moscow to have serious lobbyists at its disposal, who are able to put pressure to get sanction policy reconsidered.

Infographics 1. Trade dynamics between EU member states and Russia in January-September, 2018 (compared to the same period of 2017)

VULNERABILITY #3. Discrediting Ukraine over reforms, right-wing radicals, and the peace process

Russia is not always able to engage in a narrative that directly discredits Ukraine in other countries, since Russians generally do not enjoy much trust among Europeans. Still, there are plenty of networks, coalitions and partnerships at all levels in Russia, both at the political and the non-government levels, which make it possible for Moscow to get out its messages, which are then picked up by local players—politicians, journalists and analysts. Most often, Russia has emphasized and will continue to emphasize three main ideas: nothing in Ukraine has changed for the better since the Revolution of Dignity; Ukraine’s leadership supports and spurs radical rightwing attitudes in Ukrainian society; the Ukrainian government is not interested in peace. Obviously, Russia has also tried plenty of other messages that might find fertile ground in one country or another.

Where are the reforms?

One of the narratives that is used in France, for instance is that Ukraine and Russia are equally corrupt, both of them at almost the same level in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. And so, sometimes discussions in Paris raise the argument: why should we support Ukraine and introduce sanctions against Russia? Where in 2014 this kind of comparison did not work, it looks a lot more convincing today, meaning that Ukraine has had plenty of time to reform. In Greece, an equally popular narrative, particularly among leftish forces, is that Ukraine never had a real revolution and the oligarchs have remained in power.

Where are the liberal values?

It’s also possible that Russia will suggest in key capitals that they should jointly fight far-right radical populism and its extremist manifestations in Ukraine. This is the case with Italy, Germany and Greece, where Russia is actively drawing such parallels with Ukraine. Moreover, the “nazi Ukraine” narrative could work in dialogue not just with leftist politicians.

Tensions in relations between Kyiv and Budapest around the issue of ethnic minorities has allowed Russia’s media and pro-Russian opinion leaders in other EU countries to spread the message that Ukraine is harassing minorities, that the radical right is resurgent, and that Ukrainians are growing more xenophobic.

In Poland, too, Ukraine has become a convenient theme for the ruling Justice and Law (PiS) party to use in competing for votes with radical rightwing political forces in Poland. Attitudes towards Ukrainians in Poland have never been overly positive, but the ruling party has also become hostage to its own politics: having decided that historical policy is a foreign policy priority and having issued many statements to the effect that Ukraine was being “banderized,” PiS simply cannot allow itself to publicly support Ukraine when right radicals in Poland are building their careers on anti-Ukrainian activities. And so, Ukraine cannot count on public events and declarations that might be interpreted as a thaw in relations, despite Poland’s support in matters that are of strategic importance to it. Russia will continue to be able to exploit this anti-Ukrainian current in Poland.

Where’s peace?

Russia keeps disseminating propaganda about Ukraine being the one guilty of the war in the Donbas, and accusing Kyiv in lacking the political will to reintegrate. In some EU countries, this idea is partly supported even among diplomats. “The law on reintegration mentions everything in the world, except for provisions about reintegration,” has come from the lips of some of the most powerful politicians in the EU.[42]

Moscow is happy to promote the idea that Ukraine has no desire to carry out the Minsk Accords, that it’s stirring violence in the east in order to avoid implementing the political phase to resolve the conflict. In Italy, politicians in power also appear to be of the opinion that Ukraine is not carrying out the Minsk Accords and some have even insisted that Ukraine should federalize.

VULNERABILITY #4. Engaging in cyber attacks

The European Union is aware of the serious threat that Russia poses to European countries in cyber security. This kind of challenge could become a particularly sensitive issue in the upcoming election campaign for the European Parliament. Germany’s government has been the target of cyber attacks, as was Emmanuel Macron’s election campaign headquarters. At least eight EU countries are insisting on a forceful response, up to and including sanctions, regarding Russia: the Netherlands, Great Britain, Finland, Denmark, Romania, and the Baltics. So far, the EU has avoided the sanctions scenario in response to cyber attacks from Russia: Italy and France, among others, have been negative about such a scenario even though France itself has suffered from such attacks.[43]

VULNERABILITY #5. Influencing Russian-speaking EU citizens

Some EU countries are aware that their Russian-speaking citizens who emigrated from the FSU are one of the key audiences being targeted by Russia’s propaganda campaigns. This affects the Baltics most of all, because of their substantial Russian diasporas. In Germany, various estimates put the number of citizens for whom Russian is their first language at as much as 3 million and more.[44] The Heidelberger Institute ran a survey 10 years ago that showed that the Russian diaspora was one of the biggest in Germany, representing 21% of all immigrants, while the Turkish diaspora had fallen to second place with 19%.[45] Obviously, after the last wave of migrants from the war in Syria, the proportions have changed somewhat, but regardless, the Russian diaspora will continue to be one of the biggest. Observers insist that it would be completely wrong to consider all these people agents of Russian influence in the country, but it’s very obvious that some members of the Russian-speaking community are starting to play a growing role in promoting Russia’s undermining activities. For instance, Russian media has been openly promoting AfD and it’s clear that the main backer of this commercial was the Russian community in Germany. In some cases, it became obvious that this party gained more votes in those areas where there were more Russian speakers.[46]

7. RECOMMENDATIONS

Maintaining EU sanctions policy is key to preventing future subversive activities on the part of Russia in Europe. Restrictive measures are the only meaningful means to demonstrate the European Union’s resolve to fight destructive outside influence. Ukraine needs to uphold these recommendations, which will help keep sanctions in place and prevent any new undermining operations by Russia.

1. Mutual benefit. Most EU countries are pragmatic and business-oriented. Ukraine can become significant for the political classes of these countries if it can show the benefits of cooperation. This could be business proposals, solidarity in resolving the migration crisis, reforming the energy sector, and so on. The logic of mutual benefit provides arguments in favor of supporting Ukraine.

2. Cyber cooperation. EU countries recognize their vulnerability to cyber threats emanating, among others, from Russia. Ukraine should initiate and support a more active partnership with the EU in this sphere. The basic platform for this could be the NATO-Ukraine Trust Fund on Cyber Defense managed by Romania.

3. Messages tailored to audiences. Ukraine’s communication efforts in other countries should be timely and targeted: messages that work in Poland won’t work in Italy. In Poland, an article by a Ukrainian government official printed in a publication that opposes the government is likely to have undesirable consequences. In some countries, like Greece and Italy, it’s more important to focus on Ukraine’s successes and not on exposing Russia. At the same time, in communicating with leftists and social democrats, it’s better to focus on human rights violations, the harassment of the press and discrimination against minorities in Russia.

4. Exchange of experience. Ukraine should exchange its own experiences with EU countries regarding best practice in dealing with Russia’s subversive activities. This needs to happen at a variety of levels, both in the governments and in the NGO sector. Regular study visits from EU countries to Ukraine should be organized for opinion leaders, especially members of the press. Any such groups should include representatives of different countries and not just limit themselves to Western Europe.

5. Ongoing high-level dialog. The key to effective cooperation to counter hybrid threats is trusting, preferably friendly relations between the top leadership of countries and between senior officials working in specific government agencies. Many EU countries are worried over post-election uncertainty in 2019, so official Kyiv must do everything it can to ensure a predictable, democratic process, at least within those areas that that depend on the government.

6. Decentralized communications. Ukraine’s communications campaigns in EU countries should not be limited to their capitals. In many countries, the regions play just as big a role in shaping political discourse. This means that Kyiv should consider the regional dimension in developing dialog with a given country. In Germany, for instance, particular attention should be paid to its eastern lands, while in Italy, Milan is worth focusing on, as many people from northern Italy currently hold key positions in the government.

7. The American factor. In talking with EU representatives, it’s a good idea not to compare the EU and the US or to make public references to Washington’s intermediating role in resolving disputes with Europeans. This doesn’t at all mean that Ukraine should stop key negotiations to reach its goals with the United States.