Article by Leo Litra, New Europe Center Senior Research Fellow, for Romanian Veridica. The article is available in English and Romanian only.

The NATO Summit in Brussels, to be held on June 14, has rekindled talks regarding Ukraine’s accession to the North-Atlantic Treaty Alliance. While the accession is being discussed overtly in Kiev, many states remain adamant.

Integration without accession

Paradoxically, Ukraine has never been closer and, at the same time, farther from NATO. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the start of the war in Donbass in 2014, NATO and its member states boosted their cooperation and support for Ukraine and for the reforms it needed. The cooperation brought Ukraine very close to NATO. At the same time, Russia’s war against Kiev made NATO members reluctant towards Ukraine’s accession. The odds of Ukraine joining NATO now are even lower than before 2014.

In the current context, “integration without accession” seems to be the best option. Many NATO members were hoping that Zelensky’s election would take accession off the table, a topic which is toxic for the “old” Europe. During the first year of his mandate, the topic was indeed largely avoided. But as efforts to find a resolution to the conflict in Eastern Ukraine hit hurdle after hurdle, Zelensky has been focusing on NATO accession.

In 2016, Ukraine called on NATO to grant the country the “Enhanced Opportunity Partner” status, which Georgia had been enjoying for a few years. Former president Poroshenko had been desperately trying to prove Ukraine is capable of developing relations with NATO, despite his prior hesitation. Poroshenko avoided topics that irritate Russia, in order to keep chances of reaching a deal with Putin alive. The moment he saw an end to the conflict is very unlikely, Poroshenko chose to turn to NATO and the EU, leaving no room for interpretation.

The Zelenski era: from hesitations to taking on the accession project

Although they are strikingly different characters, Zelensky’s evolution has been very similar to Poroshenko’s. During the second year of his term in office, Zelensky started advocating for Ukraine’s NATO accession. The document that made it official is the National Security Strategy, adopted in 2020. Unlike Poroshenko’s official policy, the document leaves no room for interpretation regarding Ukraine’s future within NATO. Also in 2020, Ukraine was granted the “Enhanced Opportunity Partner” status, which further boosted relations with NATO. By the end of 2020, Zelensky spoke publicly about NATO’s accession as Ukraine’s right to ensure its national security. There are three reasons that determined Volodymyr Zelensky’s shift towards NATO:

- Once he became president, he reviewed his approach to national security and concluded that NATO accession is the best model guaranteeing medium- and long-term security.

- President Zelensky was under the same illusion as Poroshenko when he thought he could reason with Vladimir Putin. Ever since the start of his mandate, Zelensky refrained from bringing up NATO in order not to antagonize Putin. But since Zelensky’s concessions yielded little positive impact on the negotiation process, the Kiev leader preferred not to trade NATO accession for an unknown solution “offered” by Putin.

- EU and NATO accession was strongly used by Poroshenko and his party in their official rhetoric, making it their own. Zelensky wanted to be different from Poroshenko, trying to dissociate himself from his predecessor, including by avoiding this topic. He was subsequently persuaded by his associates that he had much more to lose by letting Poroshenko take the limelight in this matter.

Relaunching the accession campaign

At first glance, relations with NATO were more dynamic than with the EU. In 2020, the Government in Kiev expected to sign the Agreement on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance of industrial products (ACAA) with the EU, and to be granted the “Enhanced Opportunity Partner” status in relations with NATO. The latter happened without much public acclaim, discretely and even ahead of schedule. The EU deal never happened, and not necessarily for reasons that have to do with Ukraine.

Starting 2020, Ukraine once again raised the issue of the Membership Action Plan (MAP), after information surfaced that Georgia could be signed up for the Plan, whereas Ukraine would be left out. In the last decade there have been at least two instances when Georgia made progress in its relations with NATO, getting out of sync with Ukraine. The experience taught Ukraine to step up its efforts in order not to miss out on the accession opportunity. But neither Tbilisi or Kiev has any clear prospects of joining in the near future. The second reason behind relaunching the NATO accession campaign was the 2030 NATO Reflection Process. Every ten years, NATO launches a wide reflection process whereby it establishes its strategy and priorities for the coming decade with the help of member states. Kiev wanted its aspirations and its bid to join NATO to be firmly recognized, as well as to identify Russia as NATO’s biggest threat over the next ten years. It was partly successful with respect to Russia, but in terms of accession, the topic was left out of the NATO strategy.

Finally, the third argument in favor of making NATO accession a priority was the change of administration in Washington, which generated new expectations in Kiev with respect to US support. The expectations were largely unwarranted, as neither president Biden nor his staff have ever made clear that the USA would push Ukraine towards NATO. On the contrary, right now the USA and the EU are trying to rehash their trans-Atlantic partnership, which means avoiding toxic topics on the bilateral agenda – and Ukraine’s NATO accession is a highly toxic topic for the old Europe.

A compromise to circumvent the blockage in Brussels

The NATO resolution of 2008 in Bucharest clearly states that NATO maintains its open-door policy for Ukraine and Georgia. Moreover, the resolution says Ukraine can become a NATO member and the Membership Action Plan is the next step in relations with NATO. Still, several NATO member states have argued against close relations with Ukraine.

The fact that Ukraine is a de facto NATO candidate is recognizable in the Bucharest Summit resolution. Yet the upcoming summit in Brussels will most likely make little mention about it. For this reason, Kiev is looking for ways to move forward. To rise to the challenge, the Government is examining the possibility of adopting a Roadmap for the NATO Membership Action Plan, strange as this may sound. Kiev might actually demand less than it already has. Yet the country’s leadership prefers to make small steps forward right now than a bigger one much later. The direction Kiev should be focusing on should be the following: the end target (accession) has been set, all we need now is to determine the course of action. Instead, Kiev contents itself with another useless resolution.

If we look at Ukraine’s Annual Action Plans since 2008, Kiev already has an accession plan – it just needs to be approved. Moreover, it is high time NATO made good on its open-door policy promises. It would need to provide a clear explanation or strategy for implementing its open-door policy, otherwise it’s just a term carrying no weight.

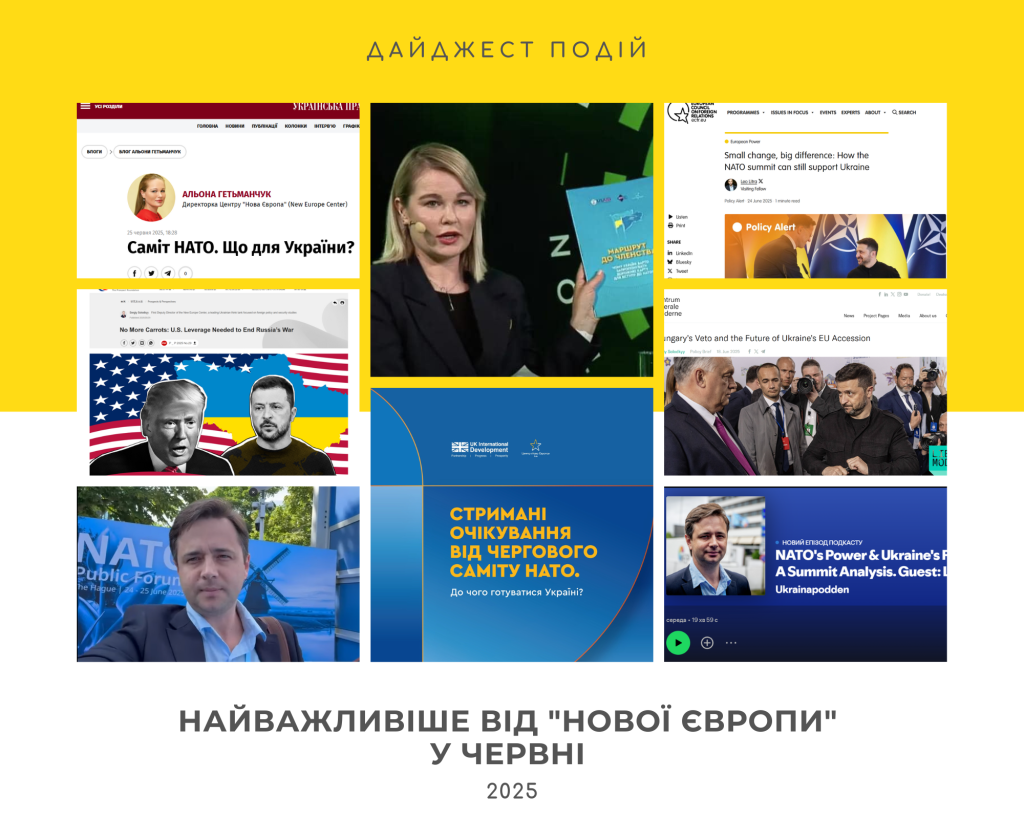

A recently published article of the Kiev-based New Europe Center shows that some Ukrainian experts believe that, to overcome the deadlock, NATO should further its existing documents – such as the Annual National Plan – by adopting a political resolution recognizing that Ukraine already has all the necessary instruments to join NATO. A similar resolution on Georgia was adopted in 2016.

Were this to happen, everyone would be happy – at least until the next summit. Otherwise, unless headway is made, Moscow’s veto right over NATO decisions would (yet again) be recognized.