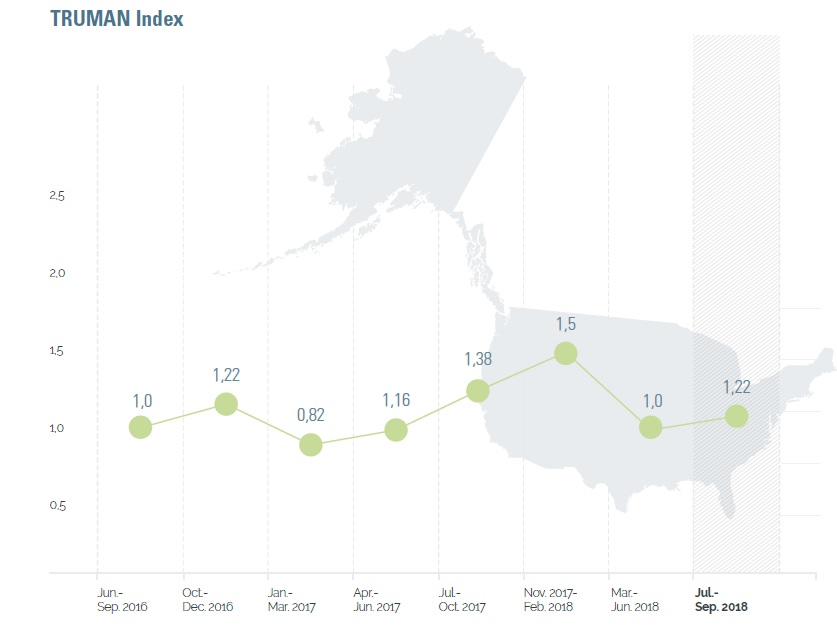

Report by Alyona Getmanchuk, Director of the NEC, on assessment of Ukraine-US relations for the quarterly magazine ТRUMAN Index. The full version of TRUMAN Index No. 4 (8) is available on the TRUMAN Agency website

July–September 2018

Positive points: +33

Negative points: -5

Total: 28

TRUMAN Index: 1.22

Update

During this past quarter, Ukrainian-American relations involved a series of mixed signals, mainly on the US side. On one hand, Presidents Poroshenko and Trump did meet, and National Security Advisor John Bolton came to Kyiv to celebrate Ukraine’s Independence Day. On the other, Trump met with Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, where the US president never once mentioned Ukraine or support for its territorial integrity publicly. The same was true of his speech before the UN General Assembly. On one hand, there were the Crimean Declaration by the Department of State and a harsh critical statement regarding Nord Stream II from Washington. On the other, there were no sanctions against European companies involved in building the pipeline and the US supported the Russian position in suits before the World Trade Organization.

Some of the mixed signals ended up playing in Ukraine’s favor. Trump’s unambiguous statements regarding Crimea made it possible for Kyiv’s friends in Washington to once again actively promote Ukraine in its habitual role of victim. However, whereas in previous years, Ukraine was presented as a victim of Vladimir Putin’s aggressive policies, after Helsinki many American stakeholders offered their sympathy and support to the country—as a victim of Trump’s unpredictable policies.

If the Helsinki meeting between Trump and Putin provided a mostly positive background for relations in other areas, the start of hearings in the Paul Manafort case proved more negative—at least for perceptions of Ukraine in the US. The high-profile court case once again drew attention to large-scale political corruption in Ukraine and US media failed to point out that this was all under Viktor Yanukovych, before the 2014 Revolution of Dignity.

This period also brought the death of Ukraine’s most consistent and reliable ally in the US Congress, Senator John McCain. Despite advice from some corners not to annoy Donald Trump by going, President Poroshenko did attend the senator’s funeral and honored this great American.

TIMELINE

Brussels overshadowed by Helsinki

Political dialog between Kyiv and Washington during this past quarter was mainly noted by a very brief meeting between Presidents Poroshenko and Trump during the NATO summit in Brussels, and a visit to Kyiv by National Security Advisor John Bolton in honor of Ukraine’s Independence Day August 24. Both events required substantial diplomatic effort on the Ukrainian side and a meeting was not given in Brussels.

As to the Bolton visit, some sources say that the Ukrainian side, and President Poroshenko personally, negotiated this visit on Independence Day directly with State Secretary Mike Pompeo. After last year’s visit to the military parade by US Defense Secretary Gen. Jim Mattis, a higher-level US presence seemed reasonable, especially as Pompeo had not yet visited Ukraine. However, Pompeo had other commitments during this time, but he promised that the Trump Administration would send a suitable representative to the event—in this case Bolton. At a press briefing in Kyiv, Bolton admitted that it was simply convenient for him to fly to Kyiv from Geneva, where he had had a five-hour meeting the previous day with his Russian counterpart, Nikolai Patrushev. One way or the other, this visit was yet another key element in establishing dialog with Bolton. At this point in 2017, he had already visited Kyiv, but as a paid speaker to a conference organized by tycoon Viktor Pinchuk. In February, several months before his appointment as NS advisor, Bolton again participated at a Ukraine event organized by Pinchuk during the Munich Security Conference.

The most significant indicator of the state of Ukrainian-American relations in this quarter could prove to be not a US-Ukraine summit but the US-Russian one between Trump and Putin in Helsinki. Despite the fact that far more attention was given to this meeting in Ukraine than to the Ukraine-EU summit or the NATO summit, both of which took place at the same time in Brussels, official Kyiv, including the president himself, made a point of publicly reacting coolly to the Helsinki meeting, its outcome and possible consequences. When questioned by journalists the day before, President Poroshenko replied that he had no expectations, good or bad, from the Helsinki meeting. During a television interview on a Ukrainian channel afterwards, he stated confidently that President Trump had held to the Ukrainian position in Helsinki. US Special Representative Kurt Volker later also reassured Kyiv that the American side did not concede any positions that might concern Ukraine in Helsinki. In an interview with Voice of America, Volker said, “There were no moves to recognize Russia’s annexation of Crimea, support a referendum, or support Russia’s position regarding the formation of an armed group to protect the monitoring mission, which could split the country.”

However, it’s understandable that Ukraine’s president and the special representative could only make these statements based on their interpretations of Trump’s talks with Putin, as only the two presidents and their interpreters really know what was said. One interpretation was voiced by SecState Pompeo at Senate hearings summing up the Trump-Putin meeting in Helsinki: No results were attained with regard to Ukraine and the two simply agreed to disagree. Obviously this concerns not just Crimea but also the situation in Donbas, where Putin suggested to his US counterpart that a referendum be held among the residents of the occupied territory No one knows how Trump reacted to this at the actual meeting, but later the White House publicly cut the idea down.

After her meeting with the Russian president, German Chancellor Angela Merkel phoned the Ukrainian president to brief him on their conversation, but this approach does not work in Ukraine-US relations. The main thing is that the Ukrainian and American presidents met before the Helsinki summit with Putin, but it would be better to have a direct channel of communication after such key meetings to avoid Kyiv having to make official requests to Washington about the content of Trump’s talks with Putin regarding the situation in the Donbas.

If the Helsinki meeting between Trump and Putin provided a mostly positive background for Ukraine-US relations in other areas, the start of hearings in the Paul Manafort case proved more negative—at least for perceptions of Ukraine in the US. The high-profile court case once again drew attention to large-scale political corruption in Ukraine, causing the US Embassy in Ukraine to request the American press to be clearer in its coverage about what period was being described—the Yanukovych Administration, prior to the 2014 Revolution of Dignity. Testimony from Rick Gates, Manafort’s former business partner, risked hitting the reputation of President Poroshenko, whom Manafort’s firm supposedly helped in 2014. Poroshenko’s office acknowledged that proposals for cooperation had come but his administration had rejected them.

Insiders in the Ukrainian government list a number of priorities in political dialog with the US today that need more attention from the Trump Administration:

- reviving the strategic Ukraine-US commission, which American partners support but seem in no rush to reinstate;

- instituting sanctions against European companies that are involved in the building of Nord Stream II;

- taking a decisive position regarding the release of Ukrainian political prisoners currently held in Russia;

- applying maximum efforts to help fight off Russian interference in Ukraine’s upcoming elections, with a special focus on cyber security and the dissemination of disinformation in social networks.

All these issues are being discussed with various US partners. Some, like Nord Stream II, have been getting specific attention at the highest level, such as during Trump’s meeting with Poroshenko in Brussels. In contrast to the American president, who can get away with publicly saying what he wants when it comes to the pipeline and Germany, Poroshenko’s rhetoric is restrained and he cannot openly call for sanctions against European companies, given the established trust in relations with Chancellor Merkel.

A fairly new accent in bilateral relations was US assistance in countering Russian interference in Ukraine’s presidential election campaign, which Poroshenko himself has raised in conversations with American collocutors over the last half-year, including Assistant SecState for European and Eurasian Affairs Wess Mitchell and Bolton. This is no surprise, given that Poroshenko is personally interested in minimizing Russian influence during the election campaign, especially in social nets, or at least making it overt. Ukraine’s incumbent president is not Putin’s candidate, and so the strongest attacks are likely to be against his candidacy. Kyiv has been positively impressed by how US agencies were able to uncover widespread Russian interference through a troll army managed by Moscow. Significantly, the US has decided to double its financial support for Ukraine to strengthen cyber security, from US $5mn to US $10mn.

Crimea and the Azov leave Donbas in the shade

One issue that strikingly moved to the back burner was a resolution of the situation in the Donbas, where the Americans and Russians are on different tracks altogether. Instead, Crimea once again moved to the fore after President Trump began issuing ambiguous messages to Russia over Crimea, starting with the G7 leadership meeting in Canada, where he refused to respond on questions as to what his further strategy will be regarding the occupied peninsula. The assumption is that this was his tactic in the run-up to the Helsinki summit. Or perhaps European Council President Donald Tusk got it right when he said, after several meetings with Trump and discussions about Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine initiated during these meetings—some at the request of Ukrainian officials—, that the overall impression was not reassuring: Trump demonstrated “less enthusiasm towards Ukraine and more understanding towards what Russia had done to Ukraine.”

The elements of Trump’s strategy of justifying Putin’s policies can also be read between the lines of his statements and, obviously, his reluctance to publicly condemn Russia’s action. That was evident at Helsinki and during his speech at the UNGA, when he blamed his predecessor for the annexation of Crimea, Germany for the construction of Nord Stream II, and Special Prosecutor Mueller for the investigation into Russian interference. Anyone was fair game—anyone but Vladimir Putin.

As contradictory as it may sound, but one positive bit of news about Crimea came in what was said at the Helsinki press briefing… not by Trump but by Putin. The Russian leader noted that his American counterpart maintained a different position than the Kremlin on Crimea during negotiations and condemned the annexation. The question is why the American president couldn’t say so himself, especially as later that month, he told Reuters that he always remembers Crimea when the subject is about Ukraine. Of course, Ukraine was one of the four items on the agenda at Helsinki.

This ambiguous behavior on Trump’s part has somehow played in Ukraine’s favor. It allowed friends of Ukraine in Washington to once again position Ukraine in its historical role of victim. However, whereas in previous years, Ukraine was presented as a victim of Putin’s aggressive policies, after Helsinki, many American stakeholders offered their sympathy and support to the country—this time as a victim of Trump’s unpredictable policies. One obvious sign of support that became possible thanks to Trump’s mixed signals was the Crimean Declaration issued by the Department of State. This was worded similarly to the famous 1940 Welles declaration regarding the soviet annexation of the Baltic countries, with which the United States refused to recognize Stalin’s annexation. “As the Welles Declaration of 1940 did, the United States confirms that its state policy is to refuse to recognize Moscow’s clams to extend its sovereignty to territory that it has taken by force and in violation of international law.” The State Department’s statement was greeted positively as this is a statement in which the US not only harshly condemned Russia’s annexation of Crimea again, but also committed itself to a policy similar to its Baltic policy until Ukraine’s territorial integrity is once more stored.

Why is this important? One of the key elements to restraining further Russian aggression is for the West to maintain an unambiguous policy not recognizing and condemning the annexation of Crimea. If the US president continues to make incomprehensible nods towards a possible recognition of Crimea as Russian, this will place the entire policy of containment, including the sanctions mechanism, under question. At the same time, it’s clear that when talking about the annexation of Crimea by the Putin regime, it’s important to talk not just about a blind repeat of the Welles declaration but of an upgrade to the US Baltics policy after 1941. Non-recognition is a good first step, but the US needs to continue to pay attention to the situation in Crimea, starting with human rights violations and ending with the growing militarization of the peninsula. It makes sense for Washington to be involved in negotiations that could foster to Crimea’s reintegration into Ukraine. In short, the US approach has to be one that the Kremlin cannot possibly read as a signal that “Crimea is off the table now, so let’s agree about the rest.”

In addition to the question of Crimea, the situation on the Azov Sea joined the Ukrainian-American dialog in the last few months. Starting in April, Russia arrested more than 100 merchant vessels sailing to Ukrainian ports. Over the summer, many American experts criticize Ukraine for its overly passive response, as they saw it, to the situation. One respected US expert went so far as to call Ukraine’s attitude “a strategy of indifference.” To judge for himself what was going on in the Azov Sea, Benjamin Schmitt, a State Department official, quietly visited to Genichesk. Afterwards, State issued a very harsh statement calling on Russia to stop putting pressure on vessels in the Azov Sea and interfering in international shipping.

The Azov situation made the need for more active cooperation with the US in rebuilding Ukraine’s Navy and Marine fleets even more urgent. Discussions about how America can support this have been ongoing since 2014, but so far results have been very modest. Illustrative of the problems is the cases of the transfer of two Island-class coast guard vessels, where agreement in principle was reached four years ago. Yet the boats remained in Baltimore all this time, supposedly because of delays in procedures on the part of the Ukrainians—even though such boats would have been very useful on the Azov Sea. Only after a high-profile investigation by Radio Liberty that revealed that the tangle of red tape in Kyiv holding up the transfer of the two cutters was also in part due to mercantile interests within President Poroshenko’s circles did government officials begin to chorus that negotiations were in their final stage. At last, during Poroshenko’s visit to the US for the UNGA, the formal ceremony transferring the two vessels to Ukraine took place in Baltimore in late September.

As to regulating the situation in the Donbas, work continues on drafting a possible mandate for a peacekeeping mission and agreeing this with German partners, but both Kyiv and Washington have long ago resigned themselves to the fact that there will be little or no progress before Ukraine’s elections. “Why should Putin make Poroshenko a gift like that,” say some Ukrainian and American diplomats. “He’s better off waiting in case a politician more loyal to him gets elected and then Putin can help that person gain political capital at the beginning their term.”

Security above all else

Sources in diplomatic circles say that President Trump started his meeting with President Poroshenko in Brussels with a question along the lines of “Have you tried our Javelins yet?” In fact, as is known, Ukraine can only use them on parade if the situation on the front doe not change and Russia does not attack openly. The Javelins were not given to Ukraine to be used as desired, but came with many strings attached. This means that, either Trump was ill informed about the terms on which the Javelins were provided to Ukraine. Or maybe he was simply hinting that it was time to add some purchases to what Kyiv had received for free.

All the more so that American collocutors say that one of the arguments that persuaded Trump to allow these weapons to go was that Kyiv would later on start buying them. This is what left some very puzzled and confused in Washington when they found out about an agreement signed just one month after the delivery of the Javelins—only not with the US but with France, where Ukraine decided to buy Airbus Helicopters worth €555mn.

Ukraine’s Ambassador to the US, in Kyiv for a session among ambassadors, did not restrain himself and publicly criticized the lack of coordination in such sensitive issues in Ukraine’s government agencies and the way that procurements were being prioritized. So far, 90% of the assistance being provided to the General Staff has been from the US, adding up to nearly US $1 billion to shore up security since 2014.

Obviously, the French deal is reflective of internal competition factor: the contract on helicopters was put together by Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, burnishing his own reputation in the French capital. Not surprisingly, the Poroshenko Administration, which is directly in communication with its American counterparts, came down on the American side, criticizing the French deal, which was, among others, not transparent.

Clearly, too, after the deal with France, it will be harder for Ukraine to argue the lack of such contracts, lack of funding, or other problems, with its main security partner, the United States. In order not to lose the dynamics of buying the support of the US president, earned earlier by buying Pennsylvania coal and a billion-dollar contract with General Electric, the Ukrainian side inquired with Trump about buying more anti-aircraft systems. One such unit is worth US $750mn and the UA army needs at least three. During his meeting with Trump in Brussels and his later meeting with Bolton, Poroshenko mentioned other needs: for drones, for counter-battery radar systems and for counter-sniper systems. This is not a US $4.7bn deal, like Poland’s purchase of Patriot systems from the US, but nevertheless a desirable step. Given Trump’s tendency, according to different sources, to continue to form his attitude towards different countries based to a large extent on two indicators—how many weapons they will buy from the US and to whose benefit is the trade deficit with the US—, this makes eminent sense.

It’s no surprise, then that propositions for procuring US weapons systems and equipment, rather than freebies, are more and more part of the rhetoric of American partners. Kyiv gets that, and the Americans are providing incentives within the framework of the Pentagon’s Foreign Military Sales program. This allows Ukraine’s Defense Ministry to sign intergovernmental contracts with the US and buy weapons and military technology without intermediaries—provided some legislation is changed.

On August 13, President Trump signed the National Defense Authorization Act for 2019, in which US $250mn is allocated for Ukraine. This is US $100mn more than in the current defense budget. In accordance with the related 2017 law, Ukraine will be able to access half of this sum unconditionally while the rest has some well-defined strings attached. One key condition is that Ukroboronprom, the state-owned weapons manufacturer, has to be reformed, and in this respect a US advisor is scheduled to visit in October. American assistance to Ukraine is clearly providing incentive to reform the security and defense sectors.

Earlier, on July 1=20, the Pentagon announced that US $200mn was being allocated to Ukraine for 2018 in its budget as well. The main condition here was that Ukraine pass the law on national security. In September, the US Congress approved the Pentagon budget for 2019, in which US $250mn is allocated to Ukraine, US $50mn more than this year.

The death of a great friend

Despite positive signals from the Trump Administration, the State Department, the Pentagon, and the House of Representatives, Ukraine’s biggest friend at the official level was the US Senate. In the last few months, the Senate constantly demonstrated that it had tight control over the Ukraine question. It was clearly no mere coincidence the Congress’s Crimean Declaration appeared just before hearings in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. SecState Pompeo was invited to attend in order to report on the results of the Helsinki meeting. At these hearings, the Committee also approved a bipartisan Senate resolution condemning the annexation of Crimea and confirmed America’s absolute commitment to Ukraine’s territorial integrity and to continue to support Ukraine in the face of Russia’s aggression. Within a few days, senators also submitted a bill to Congress on strengthening economic, political and diplomatic pressure on Russia in response to “the Russian Federation’s continuing attempts to interfere in US elections, Russia’s malicious influence in Syria, its aggression in Crimea, and other actions.” The authors of the bill included Lindsay Graham (R), John McCain (R), Bob Menendez (D), Ben Cardin (D), Jeanne Shaheen (D), and Cory Gardner (R).

For this reason, Kyiv will carefully monitor how the Senate changes after November’s mid-term elections to the Congress. There are some fears that the Foreign Relations chair, Bob Corker (R) will be replaced.

This period was also distinguished with the loss of Ukraine’s most consistent and uncompromising ally in the US Congress, Senator John McCain. McCain empathized with Ukrainians during both Maidan revolutions. Like many both in Ukraine and in the West, he was deeply disappointed in the outcome of the Orange Revolution and he did not hide this in conversations over 2009-2010. At both meetings then, he recalled his trip to Crimea, a trip that seemed to stick in his memory more than any other during the Yushchenko Administration. In contrast to many western politicians whose disenchantment with the Orange Revolution made them turn away from Ukraine altogether, McCain was one of those whom the Revolution of Dignity stoked up again and spurred to invest new efforts into Ukraine. Russia’s aggression, in turn, almost made this a moral imperative for him.

Despite McCain’s role in relation to Ukraine in US politics, President Poroshenko’s decision to fly to the senator’s funeral was apparently not automatically approved in all corners in Kyiv. Some officials, knowing Trump’s hostility towards the late senator, worried that the US president might take it as a personal affront if Poroshenko were there and this might eventually affect their relationship. Still, the conviction that Poroshenko was now morally obligated to honor Ukraine’s great friend won the day. The decision proved to be the right one and the fears appear to have been unfounded, as the funeral was attended by other members of the Trump Administration and even members of his family.

Events in Ukraine-US relations (July – September 2018). Point-based evaluation

| Date | Event | Points |

| July 2 | White House spokesperson Sarah Sanders announces that the US does not recognize the annexation of Crimea of Russia and will not weaken sanctions against the RF. | +1 |

| July 9 | The opening ceremony for Sea Breeze 2018 takes place in Odesa, a military exercise involving 19 countries and more than 2,000 service personnel. | +1 |

| July 12 | Presidents Poroshenko and Trump meet at the NATO summit in Brussels for about 20 minutes according to Ukrainian sources, with Nord Stream II one of the priority topics. | +4 |

| July 20 | The White House announces that it will not consider supporting Russian President Putin’s proposal for a new referendum in occupied Eastern Ukraine. US Security Council spokesperson Garrett Marquis notes that agreements between Kyiv and Moscow to resolve the conflict in Donbas do not offer any option of a referendum and any attempts to organize such a referendum will entirely lack legitimacy. | +1 |

| July 20 | For the first time, Ukraine starts up an AES power unit running entirely on American fuel: the third unit of the Southern Ukraine AES now uses fuel rods from Westinghouse rather than Russian rods. By 2020, the second power unit at the Southern Ukraine AES is expected to switch completely to American fuel, as is the fourth unit at the Zaporizhzhia AES. | +1 |

| July 21 | The Pentagon announces that it will allocate US $200mn to Ukraine for defense purposes in its 2018 budget, a decision that was made possible with the passage of Ukraine’s Law on National Security. The money is intended for military equipment and training for military personnel. | +1 |

| July 25 | US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo presents an outline of official American policy regarding the restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. In the “Crimean Declaration,” the State Department confirms US commitment to the policy of not recognizing Crimea’s annexation. This document is the first time that the US has linked its policy of non-recognition and its non-recognition of the soviet annexation of the Baltic countries in the 1940 Welles Declaration. | +2 |

| July 31 | As the Paul Manafort case goes to court, it is revealed that Manafort opened 30 bank accounts in three countries to hide the profits from his work in Ukraine. Altogether, he earned about US $60mn during his years working for Yanukovych. Manafort’s former business partner says that in 2014 they helped Petro Poroshenko, a claim that the Presidential Administration denies. | -1 |

| August 1 | Three trade disputes with Russia being considered at the WTO go against Ukraine. The WTO panel sides with Russia against Ukraine’s protective duty on imports of Russian ammonia. Ukraine also loses its suit against Russia’s refusal to certify Ukrainian railway equipment. The US sides with Russia in this dispute. | -1 |

| August 2 | A group of US senators submits a bill to Congress on strengthening economic, political and diplomatic pressure on Russia in response to “the RF’s continuing attempts to interfere in US elections, Russia’s malicious influence in Syria, its aggression in Crimea, and other actions.” | +1 |

| August 8 | President Poroshenko speaks to SecState Pompeo over the phone. | +2 |

| August 13 | President Trump signs the National Defense Authorization Act for 2019, which includes an allocation of US $250mn for Ukraine, US $100mn more than in the 2018 budget. | +3 |

| August 21 | President Trump tells Reuters, a new agency, that he is not considering withdrawing sanctions against Russia and would begin to consider this possibility only if Russia took some steps in the right direction. | +1 |

| August 24 | US National Security Advisor John Bolton visits Kyiv, where he announces, among others, that the crisis around Ukraine needs to be resolved “asap,” because it’s dangerous to leave the situation in Crimea and Donbas as it currently stands. | +3 |

| August 25 | Senator John McCain, possibly one of Ukraine’s most visible and most consistent supporters in Washington, dies after a long struggle with cancer. | -3 |

| August 29 | Ukraine’s Ambassador to the US Valeriy Chaliy tells Radio NV that Ukraine has applied to the US to purchase at least three anti-aircraft defense systems worth US $750mn each for its Armed Forces. | +2 |

| August 30 | The US State Department posts a notice on its site calling on Russia to stop harassing ships in the Azov Sea and not interfere in international shipping lanes. | +1 |

| September 3 | Rapid Trident 2018 is launched at the Yavoriv base with more than 2,000 service personnel from 14 countries participating in the military exercises. | +1 |

| September 5 | The US and EU issue a joint statement expressing concern that a Ukrainian court has granted the Prosecutor General access to information from the cell phones of TV journalist Nataliya Sedletska: “The Ukrainian government needs to support independent journalism.” | +1 |

| September 11 | US Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom Samuel Brownback arrives in Kyiv, where he meets with President Poroshenko. This visit is particularly important in the context of establishing an autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church and the position of the country’s international partners, including the US, on this issue. | +1 |

| September 11 | The first General Electric locomotive is delivered to Ukraine at the Port of Chornomorsk. GE has already shipped a second locomotive called “Trident,” due to arrive on September 24. | +1 |

| September 27 | President Poroshenko arrives in Baltimore to participate in a ceremonial transfer of two Island-class coast guard vessels to Ukraine. The decision to donate these boats was approved back in 2014 under the Obama Administration. | +2 |

| September 28 | President Trump signs the 2019 Pentagon budget, with US $250mn allocated for Ukraine, which is US $50mn more than in the 2018 budget. The budget was passed in the House of Representatives and Senate earlier in the month. | +3 |