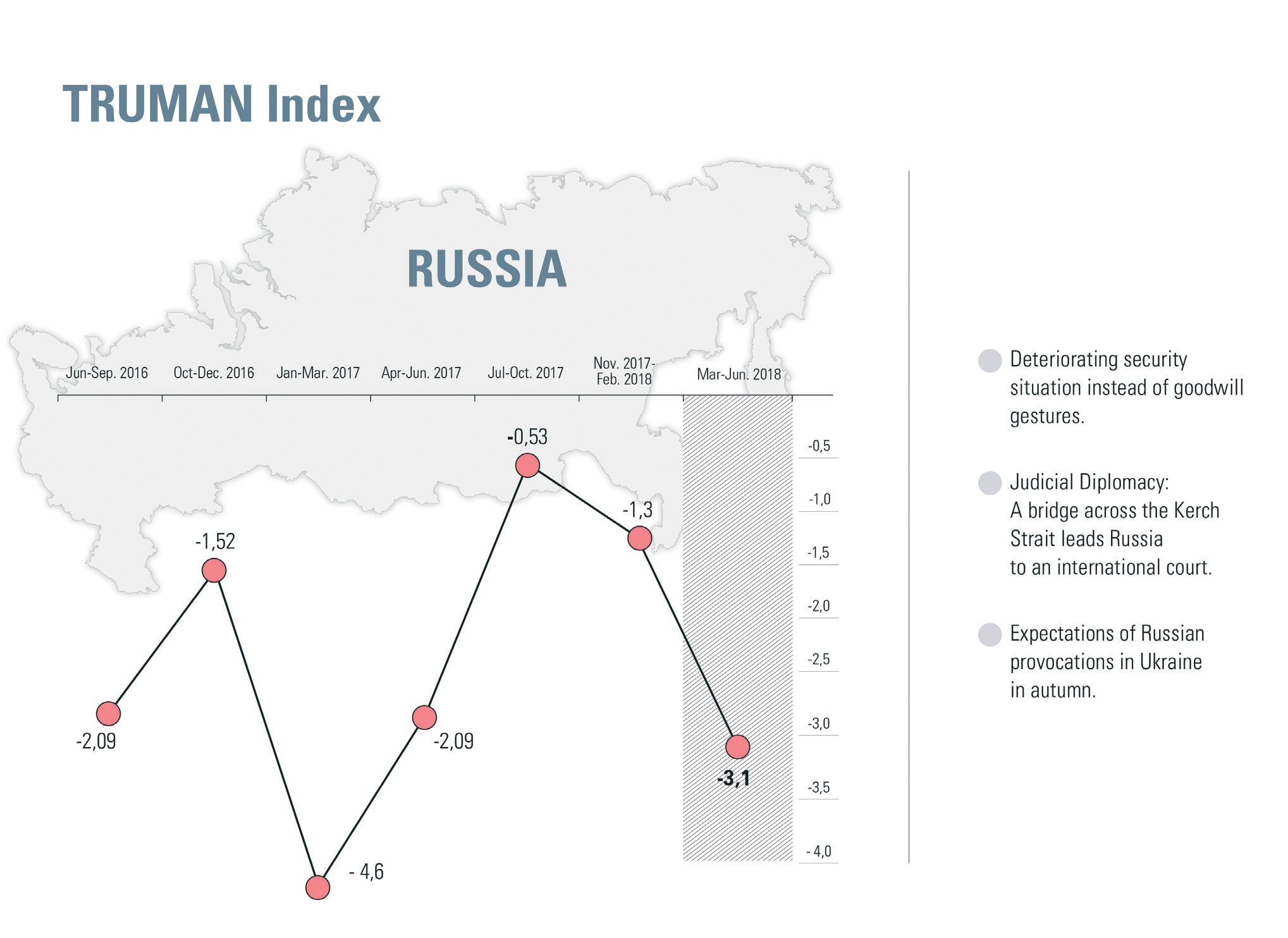

March – June 2018

Positive: +3

Negative: -68

Overall: -65

TRUMAN Index: -3.1

UPDATE

This quarter was saturated with mutual rebukes and an escalating security situation in the Donbas. Serious accusations were made about the involvement of Russian intelligence services in preparing large-scale acts of terror in Ukraine. One special operation in response to a supposed Russian plot—the faked assassination of a Russian journalist living in Ukraine—seems to have backfired and become more of a fiasco than a victory in terms of gaining international support. That could be one reason why foreign actors did not respond especially harshly to warnings from Ukraine’s leadership about Russia’s preparations for broad-scale provocations this coming fall. Still, in unofficial conversations, western diplomats often question how Russia is likely to behave during the election campaign in Ukraine. There are no doubts on any side that Moscow will interfere. The only questions are how, and what the impact will be. Both in Kyiv and in western capitals, there was some hope that Vladimir Putin might make some gestures of good will during the world football championship, but the miracle did not happen in this reporting period. Ukraine continued to hope to put pressure on Russia using two kinds of leverage: international sanctions and international lawsuits. Still, these instruments don’t always work, as certain bits of news in this quarter have demonstrated, such as the opening of the bridge across the Kerch Strait and Germany’s go-ahead to Nord Stream II.

TRUMAN Index of relations between Ukraine and Russia is -3.1 points, which is more than twice as bad as the previous index. This is because the previous period was filled with much-promised events, such as the release of hostages or the start of talks over a UN peacekeeping mission, which stirred a baseless hope that the war between the two countries might end. This latest quarter confirmed the pointless nature of the expectations that emerged half a year ago: the process of prisoner exchanges ground to a halt once more and the peacekeeping mission keeps being discussed but Russia has shown no willingness to compromise.

TIMELINE

OLD EXPECTATIONS OF NEW PROVOCATIONS

In this last quarter, expressions of concern that Russia was preparing for large-scale provocations, including military assaults, grew morefrequent in Ukraine. These came most often from the National Security Council and the Foreign Ministry, and most of them were connected to the fact that Ukraine has entered the active phase of the 2019 election campaigns, one for the presidency and the other for the Verkhovna Rada. Kyiv is pretty certain that Moscow will attempt to influence the results, including through its leverage over the dynamic of the conflict. Last year, Ukraine was also seriously concerned about Russia’s planned military exercises in Belarus. Key NATO members also issued statements calling on Moscow to avoid escalating tensions in the region. This time, though, there were few expressions of concern on the part of top western leaders that Russia might interfere on a large scale.

Ukraine’s intelligence agencies report that Russian intelligence agencies are also actively involved in organizing provocations involving ethnic minorities in Ukraine: in the last year 41 incidents of extremism were reported. Some of the special ops have been commissioned by the so-called Ukraine Salvation Committee, which was organized by political fugitives from Ukraine who are now living in Russia, including former PM Mykola Azarov. In this way, Moscow appears to be trying to discredit Ukraine in the world and to set the country at odds with its neighbors.

International actors have been more and more cautious in their responses to such pronouncements from the Ukrainian government. This distrust may have been spurred by overall fatigue with the subject of Ukraine, something that the scandalous special operation with the staged murder of Russian journalist Arkadiy Babchenko may have increased. Although the SBU insisted that it was working to prevent a series of terrorist acts that were being prepared for Ukraine by Russian intelligence services, western capitals found official Kyiv’s explanations less than convincing. On one hand, they are more than aware that Russia is quite capable of aggressive attacks, but on the other, they don’t understand why Ukraine chose to execute an unprecedented deception without ultimately producing persuasive evidence. In unofficial communications with western diplomats, there is often a sense of skepticism the minute they hear about the “mark of Russian intelligence services.”

At the same time, in these same informal discussions, members of the diplomatic corps of both the EU and US show continuing interest in the “Russian factor” in the election campaign period, including through engaging the military component. It seems clear that Russia will not risk any such actions at least until July 15, when the football championship is over.

It’s equally obvious that the pro-Russian wing in Ukrainian politics will become more active as the campaign rolls out. For instance, Viktor Medvedchuk, whose youngest daughter is Vladimir Putin’s godchild, intends to run for the Rada. After 2004, he focused on behind-thescenes politicking, preferring to operate in the shadows. The fact that he is returning to open politics indicates just how important

the upcoming elections are for the Kremlin and Medvedchuk’s decision was clearly not made in isolation. However, Medvedchuk’s participation also suggests that Putin no longer trusts any of the politicians representing the pro-Russian wing in Ukraine, primarily represented by such political parties as Yuriy Boyko’s Opposition Bloc and Vadim Rabinovych’s Za Zhyttia—even if Medvedchuk makes a point of speaking positively of them. That Medvedchuk plans to run in the election is evident in his recent purchase of two new television channels in Ukraine, although neither he nor the two channels confirmed this at the time of press.

Meanwhile, Kyiv can see that the threat this time comes not just from the east but also from the south, primarily the Azov Sea region. According to Ukrainian data, Russia has deployed additional forces there and is in a position to land its troops on the Ukrainian shore. Kyiv is very worried that, the completion of the bridge across the Kerch Strait allows Russia not only to block Ukrainian vessels but also to march troops into Crimea, from which it could attack the mainland. However, the Presidential Administration notes that Crimea has already been turned into a heavily armed fortress. The NSC reports that the MLRS deployed on the peninsula are already capable of attacking deeply into the heart of Ukraine. The Presidential Administration decided to specifically draw the attention of European leaders to security in the Black and Azov Seas during the Ukraine-EU summit on July 9. Kyiv was hoping that there will at least be a severe verbal response and decisive steps up to and including the institution of new sanctions. The hopes for sanctions were, of course, groundless, but in the joint final statement, Ukraine and the EU sentenced militarization of the Azov and Black Seas.

Ukraine is also worried about changes in the eastern part of the country. For instance, its military has shared information about the fact that Russia has been preparing special units on the occupied territory of Donbas to prevent the retreat of its proxies from the first line of defense. Supposedly because of this representatives of the Russian army have been beefing up rearguard units.

OSCE observers have officially noted a significant worsening in the security situation in Donbas. At the end of May, there were even reports that it was the worst fighting since the beginning of the year. Not only was it the largest number of attacks on Ukrainian military positions in the previous six months, but also on civilian targets. The National Security Council reported that there was a growing concentration of RF forces near the Ukrainian-Russian border.

All efforts to establish a ceasefire proved useless: the proxies resumed shooting pretty much the next day after the announcement of a cessation in hostilities. The efforts of Ukraine’s negotiators in the Trilateral Contact Group were focused on two main aspects: a ceasefire and the release of the hostages on the occupied territories. The Ukrainian side returned for the umpteenth time to the question of having the OSCE SMM observers present at the international border between Ukraine and Russia, but the Russians refuse to even discuss this. Kyiv insists that this is intended to prevent Russia from supplying weapons. Moscow argues that it refuses because it has nothing to do with the conflict.

Ukraine was hoping to see a ceasefire agreed at least for the two summer months, July and August. Ukraine’s diplomats noted that it has become much harder to negotiate with the Russian side lately. Their refusal to compromise is supported by the ambiguous behavior of western partners: Donald Trump’s statements about how desirable it is to return Russia to the G7, the weakening of the European Union due to various crises, such as Brexit, the growing presence of radical pro-Russian politicians, and so on.

PSYCHOLOGICAL MANIPULATION, NOT GOOD WILL

The conflict in eastern Ukraine began to escalate just as considerable diplomatic efforts were being made. For instance, in May, President Poroshenko met with French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel just as the situation on the front turned for the worse. Later, Macron and Merkel raised the Ukraine question in talks with Putin. They expected Moscow to offer some gesture of good will in view of the approaching football championship.

Kyiv presented its meeting with the French and German leaders as a kind of diplomatic victory, calling it “Normandy without Putin.” However, the actual meeting was not especially long. There was an impression that it was largely a formality, as it took place in Aachen, where the French president was being awarded the Charlemagne Prize. Moscow understood that the meeting of the trio was no special threat and that they would all have to work things out with Putin. There was no fundamental change on the issue of a UN peacekeeping mission in eastern Ukraine. Putin continues to insist on three main conditions: firstly, it will not be a proper peacekeeping mission but a security detail to protect OSCE observers; secondly, Kyiv has to agree the mandate of the ‘mission’ with the leaders of Russia’s proxy states; and thirdly, the ‘peacekeepers’ will not have access to the state border.

Ukraine had also hoped that the gesture of good will on Putin’s side would be the release of the country’s citizens who are being held in Russian prisons. This issue was the topic of two telephone conversations between Petro Poroshenko and Vladimir Putin in June after a four-month break since the last high-level call. Negotiations were initiated by the Ukrainian side, which the Kremlin particularly insisted on.

After a large-scale release of Ukrainians held hostage on the occupied territories of Donbas in December 2017, Kyiv expected that, this year, those Ukrainian citizens held in Russian prisons would also be released. However, so far, no one has been released. In fact, the hostage exchange with the Russian proxies that was expected to

happen at the beginning of the year never took place, either.

When filmmaker Oleh Sentsov announced May 14 that he was going on a hunger strike until 64 of his fellow incarcerated Ukrainians were released by Russia forced both Kyiv and its international partners to act more decisively. For the first time in four years, the subject of political prisoners was discussed during a ministerial meeting in the Normandy format on June 11. A few days later, Ukrainian Ombudswoman Liudmyla Denysova travelled to Russia to carry out the agreement arranged between the Ukrainian and Russianpresidents. She was supposed to meet with Ukrainian prisoners, starting with Oleh Sentsov, Mykola Karpiuk and Roman Sushchenko. But when she arrived at the penal colonies, she was not allowed in. Moscow claimed that there was no legal basis for her to have access and that supposedly there first should have been an agreed schedule for these visits.

Kyiv saw this as a stalling maneuver because Moscow had no real intention of making any concessions. The assumption in Kyiv was that this was payback for Ukraine supposedly trying to spoil Putin’s moment in the sun during the football championships. The Russian leader may have been particularly angry over Ukraine’s appeal to the international community and the ensuing sharp statements issued by the US State Department and the European Union. Most likely he was not too happy about the fact that Ukrainian officials were overly confident in conjecturing that Putin would agree to release prisoners during the championships as a PR move. Instead, Russia went for psychological manipulation, neither refusing directly nor agreeing.

A diplomatic scandal took place that Kyiv feared could also turn into a major irritant in talks between Ukraine and Russia regarding the release of Ukrainian prisoners and give Putin more ammunition in settling accounts. In March, a chemical attack on British soil intended to kill a former Russian military intelligence officer and his daughter turned into the diplomatic scandal in relations between Russia and the West, and resulted in the expulsion of 153 diplomats from 28 countries. Ukraine joined the UK’s initiative and expelled 13 Russian diplomats from Kyiv.

Immediately a major debate began in Kyiv about why Ukraine had taken so long to expel Russians accused of spying. In diplomatic circles it was pointed out that these expulsions were largely symbolic: Ukraine simply showed solidarity with Great Britain. Some argue that Russia has no reason to send out spies under diplomatic cover, as this would be too obvious. Much better to expand the spying network within Ukrainian government agencies. For instance, in December 2017, the SBU exposed a Russian spy who was working as a translator for Premier Groisman.

THE BRIDGE THAT TAKES RUSSIA STRAIGHT TO COURT

For a long time, Ukraine consoled itself that Russia would not succeed in building the bridge across the Kerch Strait. The arguments were many: lack of money, especially under pressure from sanctions; construction was too complicated; Russia would not dare because it would lead to a strong international protest. None of it proved true. For Russia, the bridge across the Kerch Strait was more than just a symbol but also a strategic link to Crimea, so Moscow threw all the resources it could at the project. Indeed, the construction of the bridge even involved companies from countries that had placed sanctions against Russia.

Kyiv had to admit that the options for responding to such actions were pretty limited. The international pressure that Ukraine called for did not work. What’s more, western governments often looked the other way when their companies cooperated with Russia until a number of major public scandals erupted, such as the one involving Siemens’ sale of turbines for a power station in Crimea.

All that was left was to turn to international courts. But even here, there are many questions: Russia can simply not recognize the jurisdiction of a court and often ignores any rulings. This happened, for instance with temporary precautionary measures issued by the UN’s International Court on April 19, 2017. The court required Russia to restore the Crimean Tatar Medjlis and stop persecuting ethnic minorities.

The years-long epic at The Hague between Ukraine and Russia has also entered a new phase. Official Kyiv submitted a Memorandum in a case involving the application of the International Convention on the Prohibition of Financing Terrorism and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. This was, in fact, a submission of evidence of Russia’s responsibility. Most of the focus was on the part that involved violations of the Convention on financing terrorism. Last year, The Hague’s judges refused to institute temporary precautionary measures related to this document, so Ukraine’s diplomats and lawyers needed to prove the deliberate intentions of the other side. The Memorandum accuses Russia of supplying arms and coordinating a series of terrorist acts by illegal armed formations on Ukrainian territory: the shooting down of MH17; the shelling of civilians in Mariupol, Kramatorsk, Avdiyivka and Volnovakha; and terrorist acts in Kharkiv, Odesa and Kyiv. Ukraine’s diplomats point out that there is a vast body of evidence: 29 volumes with more than 17,500 pages of testimony. This kind of volume is necessary to support what is written in the lawsuit as Ukraine is worried that Russia will once again distort every argument in its favor. The submitted documents will now be studied by the court for about 18 months.

Ukraine will have to exercise considerable patience regarding another issue: the now-built bridge across the Kerch Strait. Kyiv launched an arbitration case against Russia back in September 2016 accusing Russia of causing Ukraine considerable damage by its actions. Among others, this concerns the mining of minerals and the environmental, infrastructural and transportational impact of building the bridge without permission from Ukraine. As part of this case, official Kyiv has already submitted a memorandum and Russia has until November 19 to issue a counter-memorandum, after which Ukraine gets to respond, and then Russia has time to repeat its denials by September 19, 2019. The construction of the bridge across the Kerch Strait represents two extremely important challenges. The first is security. Ukraine is worried that it will foster the further militarization of Crimea by making it easy for Russia to rapidly deploy military equipment there. This, in turn, raises fears of a growing military threat along Ukraine’s southern mainland. The SBU has reported that Putin’s inner circle is planning provocations under the guise of “defending Russianspeaking citizens of Ukraine” this coming fall.

The second challenge is transportation. The central arc of the bridge places restrictions on shipping vessels. According to the Port of Mariupol, at least 144 vessels don’t meet the new requirements as to size, which constitutes a quarter of all of Ukraine’s ships in the region. This has already cost billions of hryvnia in losses. Ukraine’s diplomats promise to do their best to get sanctions placed against companies that took part in the construction of the bridge. Right now, what can be said is that international response to the opening of the bridge was limp. Both the EU and the US criticized the project sharply as in violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty. However, none of the international actors said anything about increasing sanctions.

During this past quarter, the gas conflict between Ukraine and Russia took on a new shape. Kyiv barely managed to celebrate its victory in the Stockholm Arbitration regarding the contract for deliveries of natural gas in 2009 when the positive ruling was suspended by a different Swedish court. Russia had turned to the Svea Court of Appeal against Naftogaz Ukrainy’s suit and so refused to pay the US $2.5bn fine that the Stockholm Arbitration had charged. On one hand, the Stockholm ruling was expected to be a kind of impetus for other court challenges against Russia’s actions. On the other, it reminds Ukraine that Russia will take advantage of the smallest legal loophole to block court rulings and ensure their further non-enforcement. Still, in Ukraine’s government offices the conviction is that no appeal will ultimately change the ruling of the arbitration panel.

The last four months were also marked by the usual extremes of approaches to Russia. The first came as growing pressure, both political and sanction-wise. The second came as dialog and reconciliation, especially with Germany giving the green light to a second pipeline bypassing Ukraine, Nord Stream II. This issue was given priority during bilateral talks between Poroshenko and Merkel. It was given particular attention during talks between Merkel and Putin. Ukraine’s government has been trying every way possible to block the bypass pipeline, but Germany has been very open about the chances of this being marginal. At least, official Berlin has not gone for it. There the project is seen as strictly commercial, so the state has no basis for interfering in it, although Germans are well aware of the political implications. Kyiv has been hoping for one of two successful outcomes: either construction will be halted by EU supranational agencies, or it will be stopped under threat of sanctions by the United States.

Berlin is also aware of the possibility of sanctions. Some German analysts have supposed that American sanctions might save the Merkel Government from political disaster, as the chancellor herself does not have the courage to block Nord Stream II. On the other hand, they also understand that such a conflict could hit Ukraine badly, primarily because a conflict between the EU and US could reach a peak and the transatlantic allies would have a hard time, if it remained at all possible, to carry on a dialog on other issues, such as support for Ukraine. Indeed, in German political circles, Kyiv is unofficially being warned to “restrain excessive glee” over possible US sanctions against German companies. Ukraine’s diplomats understand these warnings: decisions by an American leader who has been calling for Russia to be reinstated in the G7 could prove just as harmful to the country’s interests as Germany’s decision to support Nord Stream II.

Events in Ukraine-Russia relations (March-June 2018). Point-based evaluation

| Date | Event | Score |

| March 1 | Gazprom refuses to deliver gas to Ukraine for domestic consumption. | -3 |

| March 9 | The SBU announces that “handlers in Moscow” are involved in preparing terrorist acts in Ukraine with the participation of Volodymyr Ruban, director of the Officer Corps Center for Released Prisoners NGO. | -7 |

| March 22 | The SBU detains MP Nadia Savchenko. The Prosecutor General says that Russia supported plans by

Savchenko and her accomplices to commit terrorist attacks against the country’s leadership. |

-7 |

| March 23 | After two days of the latest cease-fire, Russian proxies begin shelling Avdiyivka. | -7 |

| March 25 | Ukrainian border guards on the Azov Sea arrest a fishing vessel sailing under the Russian flag. Russia’s

Foreign Ministry issues a note of protest to its Ukrainian counterparts. |

-4 |

| March 26 | Ukraine decides to expel 13 Russian diplomats in response to the chemical attack in Salisbury (UK). Moscow expels a similar number of Ukrainian diplomats. | -6 |

| March 29 | The leaders of the Normandy quartet declare their support for a “Pascal ceasefire” starting March 30. | +1 |

| March 31 | The latest ceasefire is violated. | -7 |

| April 5 | The Verkhovna Rada calls on the legislatures and governments of other countries to take steps to completely prohibit the building of the Nord Stream II pipeline. | -2 |

| April 10 | During a visit with Angela Merkel, President Poroshenko criticizes the Russian view of a UN peacekeeping mission in the Donbas. | -2 |

| April 13 | NSC Secretary Oleksandr Turchynov announces that Russia is preparing for an expanded war against

Ukraine. |

-2 |

| April 13 | The SBU reports that Putin’s circle is preparing to invade Ukraine in the fall. | -2 |

| April 22 | The NSC renews its sanctions and institutes sanctions against 1,759 individuals and 786 legal entities from

Russia. |

-4 |

| April 24 | The Foreign Ministry turns to the UN’s International Court in The Hague because of Russia’s failure to comply with the court’s order from a year earlier. | -3 |

| May 10 | President Poroshenko holds talks with Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel in a meeting dubbed “the

Normandy format without Putin.” The main topics are sanctions against Russia and a peacekeeping mission to the Donbas. |

-2 |

| May 15 | President Poroshenko accuses Russia of violating international law with the opening of the bridge across the Kerch Strait. | -3 |

| May 15 | The SBU arrests the director of RIA Novosti Ukraine Kirill Vishnevskiy and Russia “harshly condemns” the move. | -2 |

| June 9 | President Poroshenko and Vladimir Putin discuss the release of Ukrainian citizens in Russian jails over the phone. | +1 |

| June 11 | The FMs of Ukraine, France, Germany and Russia meet in Berlin to discuss how to set up a peacekeeping mission in the Donbas. | +1 |

| June 12 | Ukraine submits evidence on Russia’s violations of international law to the International Court in The Hague in a case that was first heard a year ago. | -3 |

| June 21 | In a telephone conversation with President Putin, President Poroshenko states that it is completely unacceptable that Ombudswoman Liudmyla Denysova was not allowed to visit Oleh Sentsov | -2 |

Full version of the TRUMAN Index №7 (March – June 2018) read on the TRUMAN Agency website