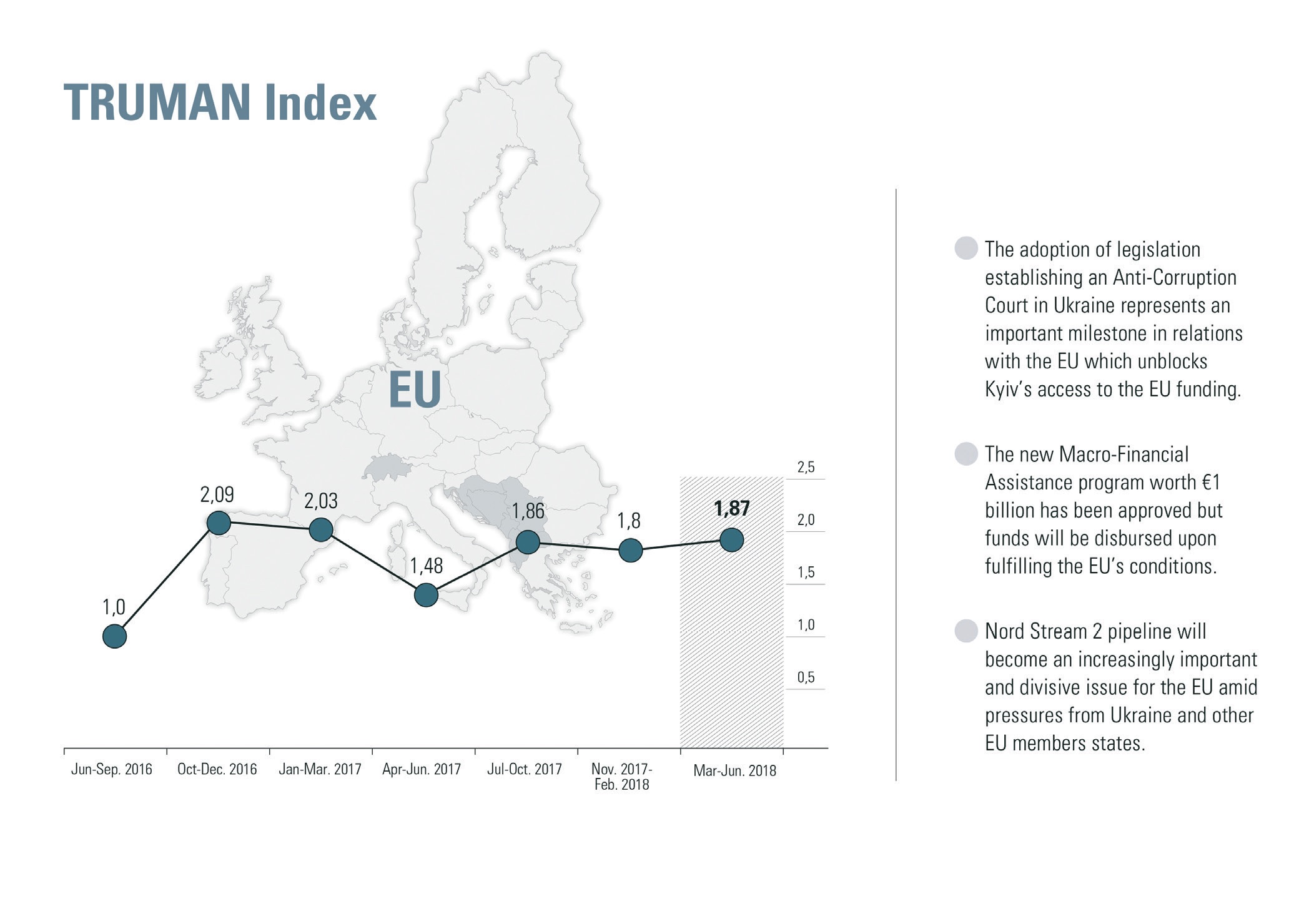

March – June 2018

Positive: +45

Negative: -2

Overall: +43

TRUMAN Index: +1.87

UPDATE

Ukraine-EU relations remained very intense during the monitored period. Unlike the previous quarter, however, this time cooperation has been very focused and many times even technical, with less politics and public statements, and more concentration on practical processes. This quarter mainly focused on two dimensions: preparations for the EU-Ukraine summit and the adoption of legislation establishing an Anti-Corruption Court.

Preparations for the summit were a relatively difficult process because a wide range of issues needs to be discussed. Among the most important are the new Macro-Financial Assistance program worth €1 billion and EU conditionalities in order to release these funds. Also, the four unions proposed by President Poroshenko at the EU-Eastern Partnership Summit in November 2017—energy, customs, digital and Schengen—have been undergoing detailed work, although the future of these projects is mixed. A separate matter of concern is Nord Stream II, which is high on Ukraine’s agenda but, so far, Kyiv has had little success in stopping the project.

The adoption of legislation establishing an Anti-Corruption Court (ACC) represents an important milestone in relations with the EU and international partners. The Anti-Corruption Court offers new impetus to relations with both the EU and the IMF and other international partners of Ukraine who are in a position to provide much-needed support for Kyiv’s reform agenda and addressing the challenges that Ukraine still faces. Still, the process of adoption has been difficult and while the outcome is positive, improvements are still required. In short, relations between Kyiv and Brussels have advanced despite a mismatch on certain issues between the two.

TIMELINE

POLITICAL DIALOG AND THE ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

The political dialog between Ukraine and the EU has been very intense and covered a wide range of issues during the monitored period. Notably, a lot of attention has been paid to the course of Ukrainian reforms and the impression that the reform process has left the international community and the EU with. “Ukraine fatigue” is once again being mentioned more often in Brussels, although one high-ranked official said that “fatigue” was the past and has turned into a “Ukraine allergy”. The problem is that, unlike one year ago, when critical remarks towards Ukraine were addressed by certain EU officials, this year even Ukraine’s best friends in the EU are more skeptical. Negative commentaries from friends of Ukraine are not meant to offend Ukraine, but to warn Ukrainians to be more attentive and less self-absorbed in bilateral relations. Moreover, there is growing opinion that many actions of certain Ukrainian officials are intended more to preserve personal wealth rather than to promote national interests. On the other hand, growing concern over Ukraine has not yet had an impact on official relations between the two.

Tensions in relations between Ukraine and the EU are being felt at all levels, including at the higher level. For instance, insiders say that the meeting between EU High Representative Federica Mogherini and President Petro Poroshenko in Kyiv was tense and continued the series of “difficult” meetings that President Poroshenko has had with Mogherini. The commissioner had not been to Ukraine for almost three years and many on the Ukrainian side were resentful that Ukraine was not a priority for her, while other seemingly less important countries were. In fact, President Poroshenko openly admitted to Mogherini that he had long been waiting for her visit. Incidentally, the EU High Representative came to Ukraine without a special occasion. Some Ukrainian officials expressed dissatisfaction that Mogherini did not opt to visit eastern Ukraine, interpreting it as a sign of her disinterest towards Russia’s aggression.

However, with the adoption of legislation establishing the Anti-Corruption Court, Ukraine has a good opportunity to improve its dialog with the EU, as this represents an important milestone for Ukraine-EU relations. President Poroshenko presented it as a major victory at the EU-Ukraine summit that took place on July 9 in Brussels. In addition to the adoption of the legislative framework, the president was supposed to deliver on a promise to cancel mandatory declarations for anti-corruption activists. However, the Verkhovna Rada failed to amend the necessary legislation early April and now the issue is likely to be a liability rather than a source of leverage in negotiations.

Another issues on the agenda are the next EU Macro-Financial Assistance program, analyzed below, and the four unions proposed by Ukraine at the EU-Eastern Partnership Summit in Brussels last November: Digital, Energy, and Customs Unions, and association with the Schengen zone.

One interlocutor in Brussels noted that the EU position on Ukraine’s proposals is clear now. The Digital Union, whose feasibility study was positive, has the best chance and there is also positive feedback on the Energy Union. However, the Customs Union and Association with the Schengen have so far been given a more negative assessment.

Ukraine also has issues it wants on the agenda. For one thing, Kyiv is unhappy with the EU with regard to the Energy Union. According to a Ukrainian source, Kyiv has delivered on 80% of its commitments to the EU with reforms in the energy sector. The major outstanding issue is unbundling Naftogaz, the state oil and gas conglomerate. However, EU apparently does not want Ukraine to become part of the Energy Union because Brussels will then have to defend Ukraine’s interests in the energy sector. This would be a big burden for the EU and would potentially require challenging Russia on energy issues.

A novelty at this EU-Ukraine summit is that both Kyiv and Brussels discussed the results on the implementation of their commitments under the Association Agreement. Ukraine insisted on this because the AA is a document that has to be implemented by both parties and both parties, at least legally, are equal.

Major attention was paid to the joint declaration after the summit. The last summit in 2017 ended without a joint declaration: although the draft was very detailed and forward-looking, the parties failed to adopt it because of reference to the recognition of Ukraine’s European aspirations. This year both parties appeared to be more flexible and a joint declaration was adopted. This is particularly important since this summit is the last one before the presidential elections and the incumbent wanted to get a positive document to strengthen his position in domestic politics and burnish his image as the only really pro-European and pro-reform politician – and did. There have been some signals that Ukraine is willing to include the recognition of Russia by the EU as the aggressor country in the declaration and convince the EU to assume the leading role in contributing to and developing a UN peacekeeping mission in eastern Ukraine. Apparently, Ukraine was also willing to have these issues discussed at the EU Council on March 19, 2018. Security issues were also going to be discussed in light of the implementation of the Minsk Agreements—or, more precisely, the lack of such implementation. Although not all of these issues were included in the final joint statement, the fact that Russia is named an aggressor is a major success for Ukraine.

The Nord Stream II project has a substantial political dimension that also came up at the summit. The EU position is that a minimum amount of gas must be shipped through Ukraine. The formula would work with GTS management by an international consortium involving Germany as a guarantee that Russia will stick to its commitments. Unofficially, sources in Brussels admit that the Nord Stream II will happen and Ukraine will lose its main transit. Some EU members may try to delay the project and make it costlier, especially Denmark and Poland. In theory, there are two ways to stop the project. One is to place Nord Stream II under EU legislation where it will be governed by EU regulations and will give EU members more leverage. The other, more realistic option would be getting the US involved in the project by sanctioning participating companies, as the Congress already adopted the necessary legislation last year. This would greatly increase the risks around Nord Stream II and the financial burden, potentially making the project unprofitable. So far, EU officials don’t seem very open to either scenario, insist, instead, that Naftogaz is unbundled and that Ukraine’s energy regulator is fully independent.

One particular issue that captured public attention was the president’s instruction to draft a bill amending the Constitution to include Ukraine’s aspirations to membership in the EU and NATO. Experts in Ukraine mentioned that, normally, such changes would have to be written into the first section of the Basic Law. But this would require 300 votes in the Verkhovna Rada and a referendum, which could not take place because there is currently no law on referenda. Besides, it will be hard to mobilize Ukraine’s voters to participate in a referendum on such an issue. An easier approach would be to include European and Euroatlantic aspirations in the preamble to the Constitution, which still requires 300 votes in the Rada, but no referendum. Still, the president did not propose changing the Constitution, because he does not have enough votes, according to one MP.

In June 2018, Ukraine celebrated one year of its visa-free regime with the EU. According to the State Border Guard Service, nearly 20.3 mn Ukrainians visited EU, almost 4.8 mn of them on biometric passports, and over 555,000 Ukrainian citizens took advantage of all the benefits of visa-free during the first 12 months. Over this year, EU border guards refused entry to 44,000 Ukrainians.

In trade, relations between Ukraine and the EU have continued to strengthen. Ukraine is already filling all its quotas on honey, malt, wheat, corn, processed tomatoes, grape and apple juices. Other quotas, such as cereals and flour, are also almost met. Among big achievements is the fact that Ukraine is now the biggest exporter of eggs to the EU, providing 38% of total supplies. Overall, the EU remained Ukraine’s biggest trade partner, taking in 42.9% of Ukrainian products in the first four months of 2018.

EU FUNDING AND MACRO FINANCIALASSISTANCE

The EU has been an important source of funding for reforms and projects in Ukraine. These days, funding for the next budgetary framework is being discussed in the EU. There are two aspects: 1) horizontal funding, defended by Mogherini, for which everyone competes, there are no clear rules and it is difficult to understand how this works, and 2) vertical funding, which is allocated for each country or group of countries and is disbursed when the countries meet the requirements. In both cases, it seems that the EU will attempt to make its funding complementary and not instrumental.

But before Ukraine can access the funding from the next budgetary framework, Kyiv will benefit from other EU funds, albeit not much. EU officials have mentioned quite often, even publicly, that the EU’s ability to provide financial assistance for Ukraine exceeds the country’s ability to absorb these funds. According to some sources, since 2014 Ukraine was unable to absorb some €5bn that foreign donors were prepared to provide. The Ukrainian side says that the overall sum is lower but admits that the problem exists. This represents a serious barrier in mobilizing the international community for a “European Investment Plan for Ukraine,” also dubbed a Marshall Plan.

Nevertheless, Ukraine has been successful in securing a new Macro- Financial Assistance (MFA) program from the EU, which has already been voted on by the relevant EU institutions and was presented at the EU-Ukraine summit. As of today, Ukraine has received loans worth €2.81bn, of which €1.61bn were allocated under the two previous MFA programs and €1.2bn under the third MFA program. The third program was debated hotly in Ukraine because Kyiv missed a third installment worth €600mn for not fulfilling all the conditions agreed. In fact, Ukraine has had a high rate of implementation – 17 of 21 conditions were met, but the remaining four conditions were more important. Among the most serious were the moratorium on the export of unprocessed timber and the automated verification of e-declarations.

The new MFA program is worth €1bn and, unlike what President Poroshenko stated in late 2017, the program will not be the same as the previous one, worth €1.8bn. The new MFA was adopted based on several factors, including the status of Ukraine’s program with the IMF. The conditions that will become part of the MFA memorandum between Ukraine and the EU are not yet known, but it is likely that the EU will continue to require conditions that were not implemented in the previous program, with the exception of the moratorium on the export of unprocessed timber. Ukraine hopes to get the first installment by September 2018, but this is not certain since, unlike in the previous program, the first tranche will likely be transferred only after fulfilling the conditions. Still, Kyiv has enough time to implement the conditions, since the MFA extends for 30 months. Despite the fact that the MFA program is a loan, Kyiv is effectively using this money free of charge for the next 15 years because the interest rate is so marginal.

Lifting the moratorium on exports of unprocessed timber will likely not be one of the conditions for the new MFA program. There are not enough votes in the Verkhovna Rada to remove it and it is unlikely that there will be enough prior to the elections. The EU has decided that there is no merit to such a condition for MFA since it will not be implemented and then Ukraine would have little incentive to implement the other conditions if no money would be forthcoming regardless.

The export of the unprocessed timber has partly continued despite the moratorium. Official statistics show that Ukraine exported only 2 t of unprocessed timber in 2017, while EU statistics show that the EU imported 447 t of unprocessed timber from Ukraine, a difference of 445 t. That suggests about that Ukraine keeps exporting but is classifying it as firewood and its Customs Service has a special approach on the issue.

To solve the problem, the EU will apply the arbitration procedure prescribed by the Association Agreement and mandatory after the first time, which is a recommendation. The arbitration procedure is launched once a group of 15 arbiters is assembled: 5 from Ukraine, 5 from the EU and 5 neutral individuals not related to either party, but on which both parties will agree. The group has been assembled by the EU and the neutral arbiters have been appointed, while Ukraine has appointed 4 out of 5. Since the appointment of the last Ukrainian arbiter has been delayed for almost one year by President Poroshenko, the EU suggested starting the arbitration procedure without the full complement of arbiters and once Ukraine appointed the fifth arbiter, that person would join an already ongoing process. According to sources, if Ukraine disagrees with arbitration based on an incomplete panel, then the EU might open a panel within the WTO instead, which might have dire consequences for Ukraine if it should lose. At any rate, the option of getting the WTO involved in the dispute was apparently mentioned in a letter from EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom. A dispute at the WTO could seriously damage Ukraine’s image. Moreover, other countries could join the challenge and would be entitled to compensation, even if they had not suffered from Ukraine’s moratorium. Finally, Ukraine might have a hard time getting zero tariff quotas and other potential improvements to the Association Agreement.

Another funding mechanism has been proposed by EU Commissioner Johannes Hahn, who offered Kyiv €50mn in exchange for reforms. Hahn called the program a contract of “reforms in exchange for investments,” which could take place as part of the new EU External Investment Plan. As it was presented by Commissioner Hahn, the grant is meant to improve the work of Ukraine’s financial market and the grant can be used as seed funding to leverage loans from IFIs and provide guarantees.

But this can only happen if Kyiv meets three conditions: full independence for the National Commission for the Regulation of Energy and Public Utilities; permanent and independent business ombudsmen; and the dropping of declarations for civil society activists dealing with corruption. All three conditions are aimed to build confidence towards Ukraine.

Commissioner Hahn’s proposal was not quite understood in Ukraine, especially because he was asking so much for such a relatively small amount of money. Some EU diplomats in Kyiv do not support Hahn’s view.

Overall, there is a wider issue with Commissioner Hahn, who has apparently “checked out” of Ukraine and is focused on the Western Balkans, since, as noted in Brussels, his advisers recommended that he focus on the Balkans if he failed to achieve a breakthrough in Ukraine. By contrast, there is a chance for him to leave behind a certain legacy in the Balkans.

REFORM AGENDA

Reforms continued to be the main priority in the Ukraine’s relations with the EU. As before, EU officials noted that there was considerable resistance to reforms in the Verkhovna Rada and partly in the Government itself. There is considerable frustration that, in four years’ time, no “big fish” has been put in jail, so anti-corruption reform remains high on the priority list. Even with elections looming, the EU continues to bring up anti-corruption efforts, although it understands that it must do it in such a way that does not offer a platform to populist forces, especially those are making hay on anticorruption issues.

The key reform in the European integration process during the monitored period was establishing the Anti-Corruption Court. The law got 317 votes, although the process was very difficult. First, MPs proposed a massive 1,927 amendments to the law, all of which had to be debated, and 4 alternative bills on top of the one proposed by the president. When the presidential bill was submitted, a wave of criticism was unleashed by the EU, G7 and other international partners who argued that the bill did not comply with the recommendations of the Venice Commission.

Second, there was a long negotiation process between Verkhovna Rada and the Venice Commission aimed at agreeing the provisions and wording of the law. Initially, most of the recommendations of the Venice Commission were agreed. The main disagreement was over the powers of the public council of international experts, which was mainly about the veto power of the international experts over the selection of individual judges for the Anti-Corruption Court. More difficult negotiations took place with the IMF. Sources say that President Poroshenko discussed various compromises with IMF Director Christine Lagarde over the phone several times.

Third, the agreed formula is that if at least 3 out of 6 members of the Council of Foreign Experts are against a given candidate proposed by the High Qualification Commission of Judges, then they can veto the decision. After that, the candidates are discussed at a special meeting between the Council and the Commission. If the majority of the joint meeting or at least half the members of the Council do not support the candidate, the latter is withdrawn from the competition. Also, the Council is allowed to hold interviews with candidates. Finally, the Court has to be completed within 12 months and will become operational as soon as at least 35 judges have been selected.

Before the vote, President Poroshenko came to the Rada to support the bill and encourage MPs to vote in favor, noting that the bill was in full compliance with Venice Commission recommendations. Most countries and institutions welcomed the successful vote on the same day—except the EU, which took note of the voting but mentioned that it would issue and opinion once the signed bill had been reviewed, because there were many amendments to the bill and the “devil is in the details.”

The EU was right to wait for the official published law because the final version contained a controversial provision that concerned criminal cases already being heard in lower courts. These were not subject to review by the Anti-Corruption Court and appeals in these cases were supposed to be considered by regular courts, even if the ACC is already operational. Interestingly, this rule was introduced in the transitional provisions.

Along with the IMF and Venice Commission, the EU immediately demanded a swift change to the controversial provision and the negotiations were taking place when this report went to press.

The other traditional anti-corruption reform discussed by the EU and Ukraine is the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption (NAPC). Some have criticized the EU for not pushing enough to have the NAPC function properly. However, the EU cannot have too many priorities and so it focused on the Anti-corruption Court, noted a member of the EU Delegation to Ukraine. The NAPC is mentioned but is not a primary focus. For the EU, the priority is rightly to have the entire legal framework in place and only then to focus on implementation. NAPC without an Anti-Corruption Court would be useless, as are e-declarations without a properly functioning NAPC.

This is bad, because NAPC will likely be used for political reasons warn experts in the field. They expect that NAPC will eventually verify the declarations of those people who are “inconvenient.” So far, the EU is worried that the NAPC will be used in the upcoming elections as a political tool to disqualify or disdain certain politicians and, says one source, there are signs that this is already taking place. From the EU perspective, “NAPC is a disaster.” Bills reforming NAPC were submitted to the Rada more than a year ago, but the process is still being delayed. The EU also expects an independent assessment of the verification system.

The EU’s main frustration is over the fact that e-declarations have not been dropped for civil society activists dealing with anti-corruption matters. Certain experts mentioned that this amendment could be annulled by decision of the Court, which would significantly simplify the task.

Events in Ukraine-EU relations (March – June 2018). Point-based evaluation

| Date | Event | Score |

| March 9 | The European Commission proposes €1bn in new Macro-Financial Assistance. | +1 |

| March 11-12 | HRVP Federica Mogherini visits Kyiv. | +3 |

| March 12 | The EU extends sanctions against 150 officials and 38 Russian companies for another six months. | +4 |

| March 16 | High Representative Federica Mogherini issues a declaration on behalf of the EU on the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol. | +1 |

| March 19 | The Foreign Affairs Council of the EU discusses Ukraine. | +2 |

| March 20 | The Verkhovna Rada adopts the European integration law on environmental assessment. | +1 |

| March 22 | MEPs urge Ukraine to maintain its anti-corruption focus and to avoid pitfalls. | -1 |

| March 28 | Commissioner Hahn issues a statement on the extension of mandatory e-declaration to civil society activists. | -1 |

| March 28 | Ukraine and the EU sign a roadmap for the integration of industry. | +2 |

| April 17 | 46 MEPs sign a letter urging a diplomatic boycott of the World Cup 2018 in Russia. | +1 |

| April 18-19 | The EU-Ukraine Parliamentary Association Committee meets in Strasbourg. | +2 |

| April 19 | The Ukrainian government signs an agreement with Germany worth €9mn for IDPs housing. | +4 |

| April 25 | The Ukrainian Government approves the Communication Strategy for European Integration. | +2 |

| May 11 | The permanent representatives committee adopts restrictive measures against actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine. | +2 |

| May 15 | The EEAS issues a statement on the partial opening of the Kerch Bridge. | +1 |

| May 22-23 | Commissioner Johannes Hahn visits Ukraine. | +2 |

| May 29 | Ukraine and the EU sign an agreement on cooperation in space under the Copernicus program. | +1 |

| May 29 | The EU Council approves macro financial assistance to Ukraine. | +1 |

| June 7 | The Verkhovna Rada passed a bill on the Anti-Corruption Court. | +3 |

| June 13 | The European Parliament approves macro-financial assistance to Ukraine worth €1bn. | +1 |

| June 14 | The European Parliament issues a resolution on Russia, notably the imprisonment of Ukrainian filmmaker Oleh Sentsov. | +2 |

| June 18 | The EU extends sanctions for one year over the illegal annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol. | +4 |

| June 26 | The Council of the European Union approves the allocation of €1bn in macro-financial assistance to Ukraine. | +5 |

Full version of the TRUMAN Index №7 (March – June 2018) read on the TRUMAN Agency website