Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty

In season two of his sitcom about an accidental president, Volodymyr Zelensky’s character gets adoring cheers after winning travel concessions for his fellow Ukrainians without setting foot outside the country.

Those days, like his meteoric rise from TV comic to the presidency, are behind him.

Instead, with visa-free travel already secured by his predecessor, Europe’s newest head of state hopes to stay on script during a two-day trip to Brussels that marks his first official trip abroad.

Zelensky’s aim, analysts say, is to set the foreign policy tone for his five-year term and show wary Western partners that he and his countrymen are serious about European integration.

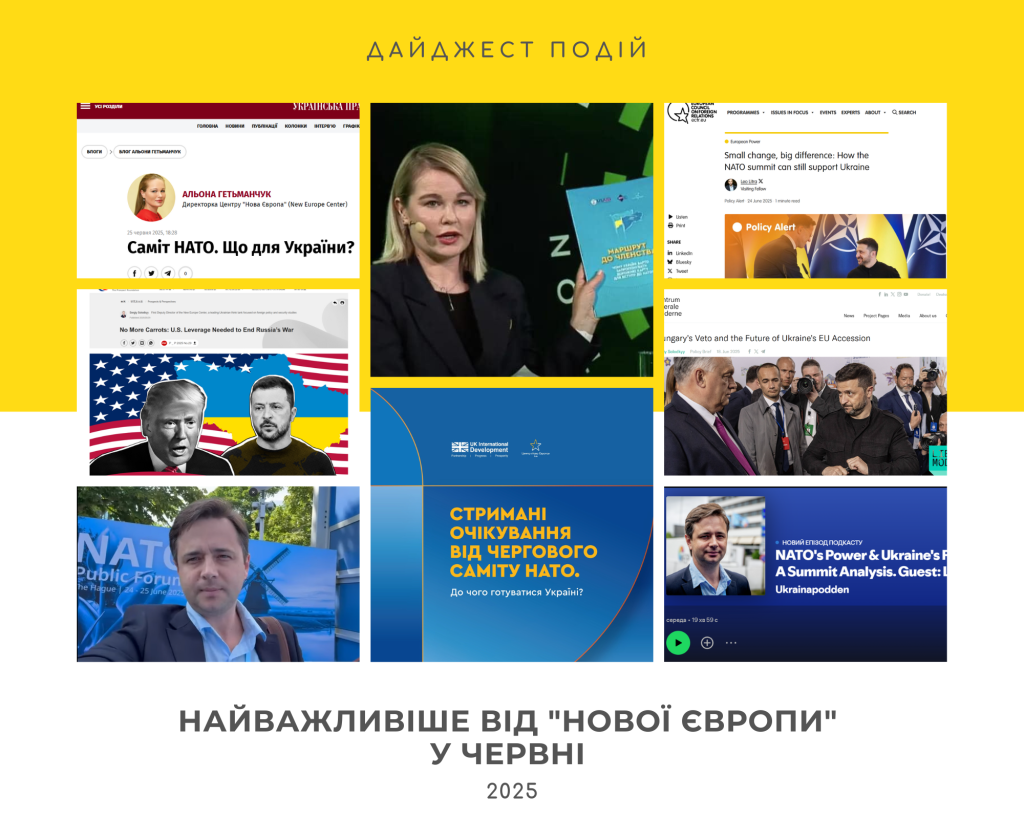

“The most important thing [for Zelensky to do] would be to reassure [EU officials] that there will be no cancellation of reforms promoted and supported by the EU but rather a continuation in reforms, not a totally new start,” says Alyona Getmanchuk, director of the New Europe Center in Kyiv, a foreign policy think tank that laid out recommendations for the president’s first visits abroad.

The verdict won’t come for some time, of course, particularly with the 28-member European Union mired in negotiations over Brexit and mutual frustrations showing in its partnership with Kyiv.

A comedian who ran a multimillion-dollar entertainment business but has no political experience, Zelensky was inaugurated on May 20 after a landslide victory over incumbent Petro Poroshenko.

Poroshenko, who spent his term courting diplomatic and military support for Ukraine’s ongoing war against Russia-backed separatists, enjoyed generally good relations with the same EU leaders who will be welcoming Zelensky on June 4 and 5.

The EU has invested heavily in Ukraine and its 44 million people, who in addition to the conflict and Russia’s occupation of Crimea face entrenched corruption and major economic hurdles. Yet Brussels has also signaled disappointment with Ukraine’s democratic failures and the slow pace of reforms.

For its part, Ukrainian discontent stems largely from the EU’s unwillingness to apply harsher sanctions against Russia. That made the new president’s choice of Brussels for his first working trip abroad popular among many political observers in Kyiv as a positive signal to key partners.

Zelenskiy’s new spokeswoman, Iuliia Mendel, told reporters during a June 3 briefing in Kyiv that the president wants “to hear again that the European Union supports Ukraine in the further struggle against Russian aggression, and also that we can count on financial and technical assistance in implementing complex reforms.”

Brussels insiders with knowledge of preparations ahead of this week’s visit told RFE/RL that the EU capital was full of expectations and that officials were cautiously eager to meet Zelenskiy after members of his team impressed them during a trip there earlier this month.

Laying Out A Foreign Policy

Vadym Prystaiko, a deputy head of Zelenskiy’s administration who worked previously as a deputy foreign minister and headed Ukraine’s mission to NATO, is with Zelensky on the trip. He told reporters last week that the trip would “demonstrate what our foreign policy is, what it was, and what it remains.”

Zelensky was scheduled to meet at NATO headquarters on June 4 with NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg and attend a session of the NATO-Ukraine Commission — a crucial format for bilateral cooperation between Kyiv and the alliance.

He will also meet with European Council President Donald Tusk, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, and Polish President Andrzej Duda.

Little is known of Zelensky’s foreign policy priorities beyond his inaugural pledges to be pro-Western and keep Ukraine on a European path while also seeking peace in eastern Ukraine. Like his predecessor, he has expressed hope that Ukraine will someday join the EU and work toward NATO membership.

“For some reason, there is some public expectation that the new president should change the main vectors of our foreign policy…or reinforce them all,” Prystaiko said after Zelensky’s recent meetings with the French and German foreign ministers in Kyiv.

Volodymyr Fesenko, a political analyst and director of the Kyiv-based Penta Center for Political Studies, told RFE/RL he expects Zelensky to more or less stay the course laid out by Poroshenko.

“Differences from Poroshenko’s policy will be in tactics and, especially, in style,” Fesenko said.

My conversations with the leaders of Europe will begin today with the question, how shall we put pressure on the aggressor together? How shall we force it to peace?”

Zelensky has yet to appoint a prime minister or foreign minister.

Fesenko predicted that whoever takes on the Foreign Ministry portfolio — Prystaiko’s name is among the few so far floated publicly — would wield significant influence, “since Zelensky himself is not very competent in matters of international politics.”

Kateryna Zarembo, deputy director of the New Europe Center, told RFE/RL that “so far Zelensky is currently looking for his own [foreign] policy model.”

Patching Up Differences

Getmanchuk said “the main difference that [Zelensky] already declared is to pay more attention to [Ukraine’s] neighbors, like Poland and Hungary, with whom Poroshenko had very complicated relations.”

Those historically strong relations have been strained by laws backed by Poroshenko’s ruling party and its allies that endorse a controversial interpretation of World War II events and the use of Ukrainian over other languages.

Zelensky’s meeting with Duda could allow the two leaders to begin patching up their relationship, experts said.

But Balazs Jarabik, a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, argued that Zelensky instead should have met those leaders in their own countries, which might have gone a long way toward mending the relationships while also setting himself apart from Poroshenko.

“He’s playing it safe” by opting to visit Brussels first, Jarabik told RFE/RL.

Support Against Russia In The War

Another big item on the agenda are talks on the war between Ukraine and Russia-backed forces in the eastern Donbas region, which has dragged into a sixth year and taken more than 13,000 lives.

On his arrival in Brussels, Zelensky wrote via Facebook that “my conversations with the leaders of Europe will begin today with the question, how shall we put pressure on the aggressor together? How shall we force it to peace?”

Fesenko noted that in the last years of Poroshenko’s presidency, negotiations with Russia over the conflict were “completely deadlocked.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin appeared even before Zelensky’s inauguration to signal that the Kremlin was not ready to negotiate. In late April, Putin signed a decree simplifying the procedure for residents of separatist-held regions of eastern Ukraine to obtain Russian citizenship. Zelensky responded by telling Putin “not to waste time trying to lure Ukrainian citizens with Russian passports.” He suggested that acquiring Russian citizenship risked “basically forget[ting] all rights and freedoms.”

But Zelenskiy has called ending the war his top priority. He has called for rebooting the Minsk peace process and the so-called Normandy Format talks that include Ukraine, Russia, France, and Germany with more “creative” approaches. He has even suggested holding a Ukrainian referendum to decide how to negotiate an end to the fighting.

Zarembo predicted that EU and NATO leaders were certain to want to hear more about the idea, which has been met with skepticism by Ukrainians who fear serious concessions to an aggressor that has sliced off chunks of their territory and fueled a war that has cost them dearly.

“The West should definitely treat the idea seriously, even if it was something that Zelensky and his staff only toyed with,” she said. “The partners can take this chance to discuss all sides of it, including dangers to the settlement process it may carry.”

Christopher Miller

Christopher Miller is a correspondent based in Kyiv who covers the former Soviet republics.