Bilateral disputes have poisoned the EU accession process for a considerate amount of time. For candidate countries like Ukraine, Albania or North Macedonia, such bilateral issues became a bottleneck for active movement towards full membership status, halting the start of formal procedures. Those blockages weaken support for European integration in candidate countries and undermine confidence in the merit-based process. So, it is crucial to find new ways and instruments to limit the impact of such disputes on the process of European integration. That is why, New Europe Center asked the distinguished experts: How candidate countries could bypass bilateral disputes with the EU member states to unlock accession negotiations? The participants in our survey are renowned experts in foreign policy and European affairs from both member states and candidate countries. Many of the experts surveyed have been or are currently involved in promoting their countries’ path to EU membership. With this survey, the New Europe Centre continues its efforts to create an expert platform for the exchange of views between representatives of candidate countries and member states in the period between our annual EU Accession Exchange Forum.

Key takeaways

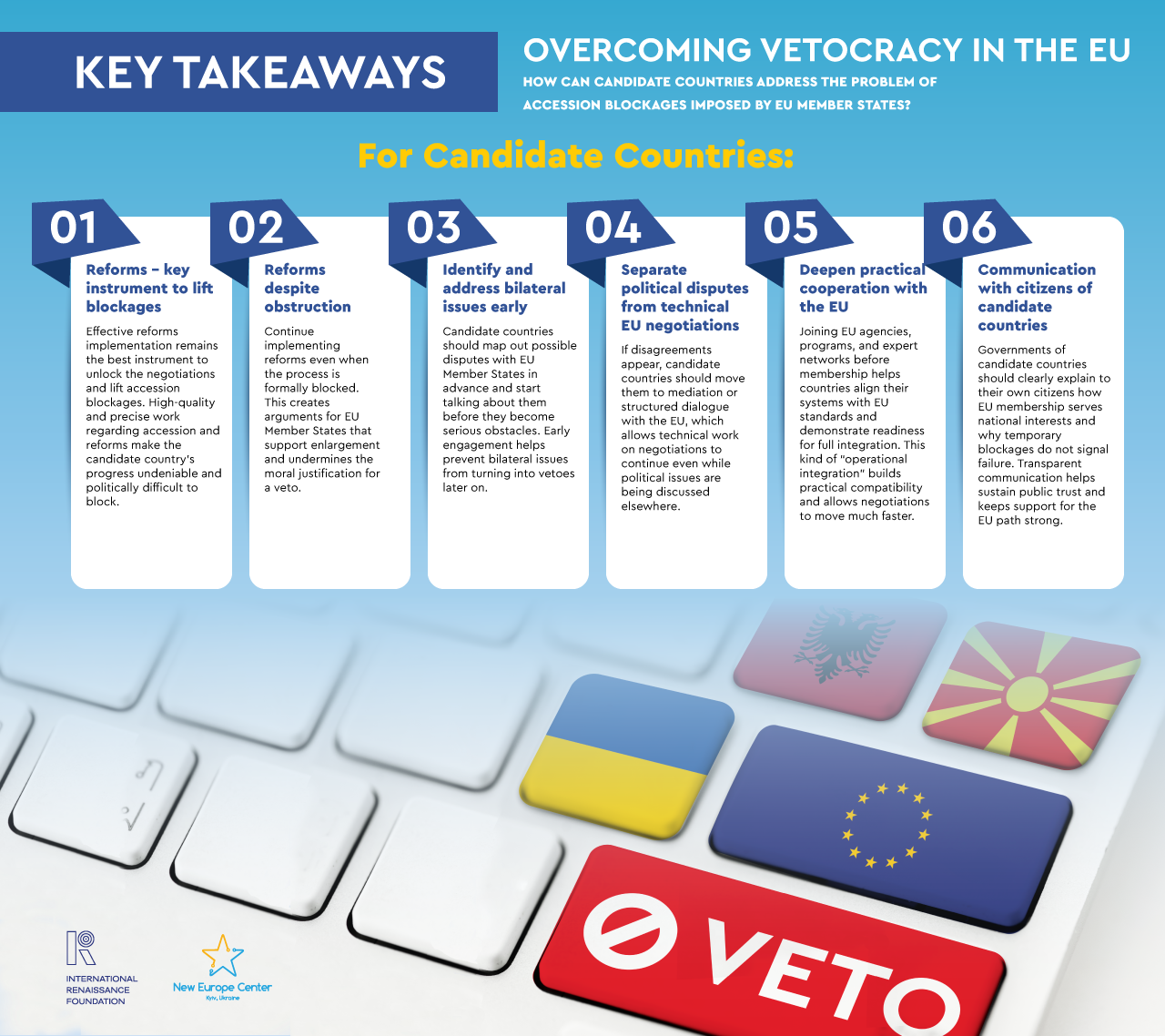

For Candidate Countries:

- Reforms – key instrument to lift blockages

Effective reforms implementation remains the best instrument to unlock the negotiations and lift accession blockages. High-quality and precise work regarding accession and reforms make the candidate country’s progress undeniable and politically difficult to block.

- Reforms despite obstruction

Continue implementing reforms even when the process is formally blocked. This creates arguments for EU Member States that support enlargement and undermines the moral justification for a veto.

- Identify and address bilateral issues early

Candidate countries should map out possible disputes with EU Member States in advance and start talking about them before they become serious obstacles. Early engagement helps prevent bilateral issues from turning into vetoes later on.

- Separate political disputes from technical EU negotiations

If disagreements appear, candidate countries should move them to mediation or structured dialogue with the EU, which allows technical work on negotiations to continue even while political issues are being discussed elsewhere.

- Deepen practical cooperation with the EU

Joining EU agencies, programs, and expert networks before membership helps countries align their systems with EU standards and demonstrate readiness for full integration. This kind of “operational integration” builds practical compatibility and allows negotiations to move much faster.

- Communication with citizens of candidate countries

Governments of candidate countries should clearly explain to their own citizens how EU membership serves national interests and why temporary blockages do not signal failure. Transparent communication helps sustain public trust and keeps support for the EU path strong.

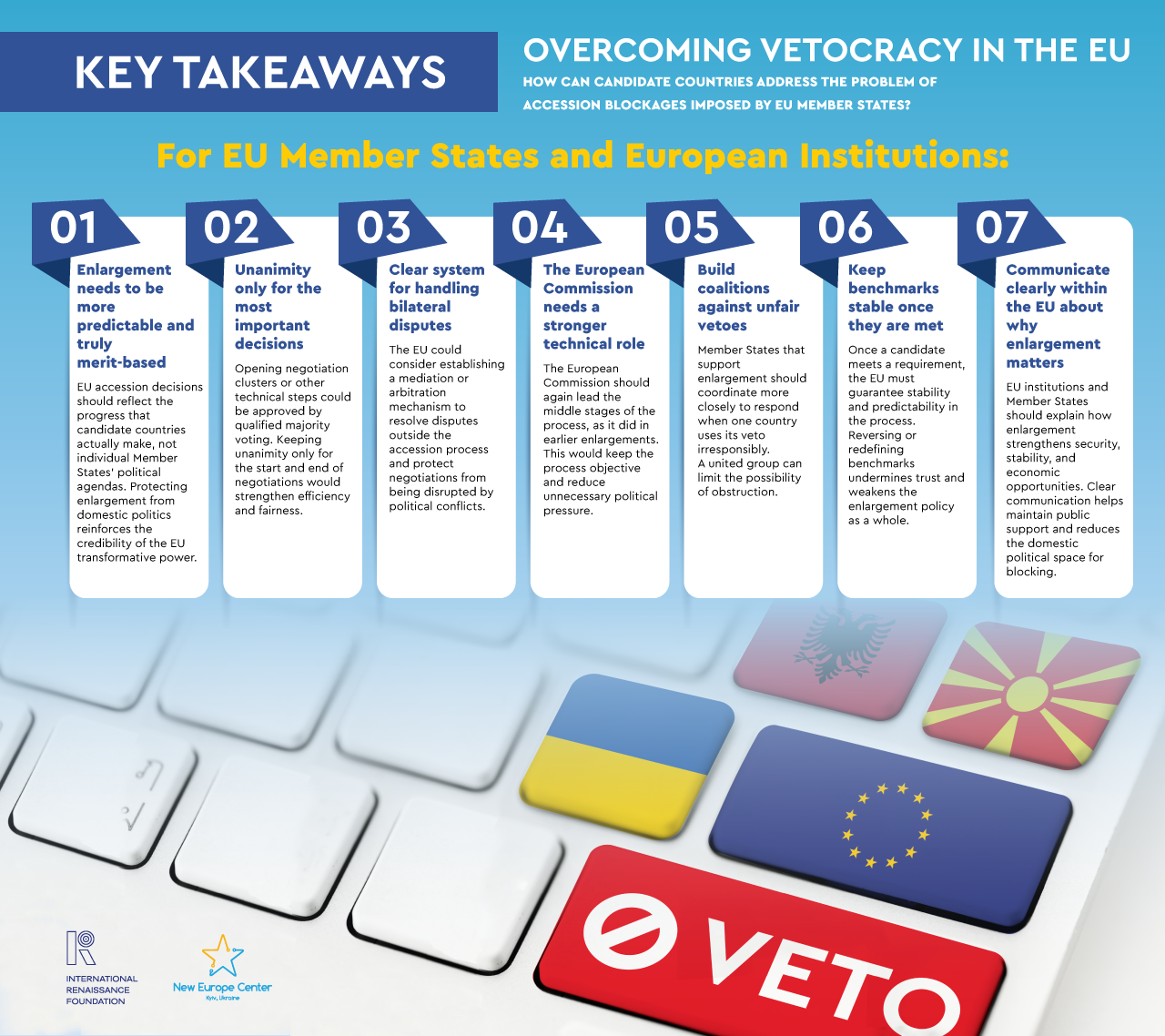

For EU Member States and European Institutions:

- Enlargement needs to be more predictable and truly merit-based

EU accession decisions should reflect the progress that candidate countries actually make, not individual Member States’ political agendas. Protecting enlargement from domestic politics reinforces the credibility of the EU transformative power.

- Unanimity only for the most important decisions

Opening negotiation clusters or other technical steps could be approved by qualified majority voting. Keeping unanimity only for the start and end of negotiations would strengthen efficiency and fairness.

- Clear system for handling bilateral disputes

The EU could consider establishing a mediation or arbitration mechanism to resolve disputes outside the accession process and protect negotiations from being disrupted by political conflicts.

- The European Commission needs a stronger technical role

The European Commission should again lead the middle stages of the process, as it did in earlier enlargements. This would keep the process objective and reduce unnecessary political pressure.

- Build coalitions against unfair vetoes

Member States that support enlargement should coordinate more closely to respond when one country uses its veto irresponsibly. A united group can limit the possibility of obstruction.

- Keep benchmarks stable once they are met

Once a candidate meets a requirement, the EU must guarantee stability and predictability in the process. Reversing or redefining benchmarks undermines trust and weakens the enlargement policy as a whole.

- Communicate clearly within the EU about why enlargement matters

EU institutions and Member States should explain how enlargement strengthens security, stability, and economic opportunities. Clear communication helps maintain public support and reduces the domestic political space for blocking.

Nathalie Tocci, Director, Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), Italy

For too long, enlargement has been hijacked by the whims of existing members seeking to promote their national interests. Be this Cyprus and Greece over Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria over North Macedonia, France (in the past) and Greece over Albania, or Hungary over Ukraine, the exploitation of the accession policy by different members to further their (legitimate or otherwise) interests has dramatically hampered its credibility by constantly moving the goalposts for applicant countries. The main route through which this poison spreads is by giving EU governments an opportunity to block the process at every stage. Viktor Orbán’s Hungary doesn’t even try to hide this intention. Yet there is nothing in EU law that requires such interference by member states, which are only requested to greenlight the beginning and the end of the process. In previous enlargement rounds, the intermediary steps were correctly treated as technical matters in the hands of the Commission. It is possible politically and legally to revert to this method. What this requires is a first mover to trigger a critical mass. Germany and Slovenia have already proposed ways to unburden the process. Other member states supportive of enlargement should follow suit. There will be outliers such as Hungary, and perhaps Bulgaria, Greece and Cyprus. But as the history of European integration proves time and again, when a critical mass builds in favour of a decision, it is very difficult for recalcitrant members to resist for long.

Iulian Groza, Executive Director, Institute for European Policies and Reforms (IPRE), Moldova

Bilateral disputes should not be allowed to hijack the strategic logic of enlargement. Candidate countries can reduce this risk through proactive diplomacy, transparency, and alignment with EU standards that make obstruction politically costly and morally unjustifiable. Early engagement with member states, confidence-building measures, and trilateral mediation by the European Commission can help depoliticize bilateral issues and anchor them within a rule-based framework.

At the same time, the EU should draw lessons from past experiences and establish clearer procedures to prevent national vetoes from derailing enlargement. Building political coalitions among like-minded member states, communicating tangible progress, and maintaining public support for enlargement across Europe are essential.

Ultimately, enlargement must remain a merit-based and strategic process, not hostage to bilateral grievances. Only by combining reform credibility with principled European unity can we ensure that the accession path remains open and transformative.

Leonid Litra, Senior Research Fellow, New Europe Center, Visiting Fellow, European Council on Foreign Relations, Ukraine

The current blocking of the accession process by EU member states for certain candidate states has become a significant issue, primarily due to some EU members leveraging their rights to obstruct unrelated processes. In the case of Ukraine, the bilateralisation of its EU accession by Hungary has reached an unprecedented level. Despite EU institutions confirming Ukraine’s fulfilment of conditions for opening several clusters, Budapest continues to veto the process.

While Hungary may be exploiting its rights within the EU framework, this issue necessitates a large-scale reform rather than mere targeted actions aimed at convincing Budapest to lift its veto. For nearly two decades, the EU clearly signalled a reduced appetite for further enlargement. Despite a number of candidate countries being in the pipeline, the EU adjusted its policies, including the enlargement methodology, effectively signalling a halt to the enlargement process. Today, the geopolitical imperative calls for the advancement of enlargement, provided candidate countries meet the required criteria. However, current EU policies continue to reflect this earlier objective – that of impeding enlargement.

Persuading Hungary to lift a single veto will not resolve the underlying issue, as numerous other opportunities exist to obstruct the process. The EU must therefore review its enlargement methodology to prevent member states acting in bad faith from undermining the merit-based approach to accession, reserving unanimity exclusively for pivotal moments such as formal accession or the closure of negotiations. It is inconceivable to envision a functional future EU while retaining unanimity for numerous secondary, often bureaucratic or administrative, processes.

Drita Abdiu-Halili, Former State Secretary at the Secretariat for European Affairs and Former Deputy Chief Negotiator of North Macedonia

The EU accession process is designed to be merit-based, yet in practice it remains as political as it is technical. North Macedonia’s experience illustrates this reality. After resolving the long-standing name dispute with Greece through the Prespa Agreement signed on 17 June 2018, the country joined NATO in 2020 and cleared all technical benchmarks for opening EU accession talks. Still, the process stalled when Bulgaria vetoed the opening over historical and language issues. The 2022 so-called French proposal, developed under the French EU Presidency as a broader EU compromise framework, enabled negotiations to begin, conditional on Skopje amending its Constitution to include Bulgarians as a minority and implementing the 2017 Treaty of Good Neighbourliness, Friendship and Cooperation. Yet progress remains delicate, as constitutional change requires broad consensus and credible assurances that new vetoes will not again block the path — an assurance hard to guarantee under the EU’s unanimity rule.

Ukraine’s trajectory reflects similar challenges. In the enlargement process, unanimity is a binding principle — not an exception — and any member state may block progress for political, bilateral, or procedural reasons, including incomplete fulfilment of accession criteria. Recognizing this reality, Ukraine’s strongest path lies in deep and sustained reforms combined with diplomatic engagement, acknowledging that the rules of unanimity cannot be bypassed but must be managed through trust and consistency. At the same time, the EU must work to safeguard the integrity of the process — ensuring that unanimity serves as a tool for accountability, not as an instrument of obstruction.

Jovana Marovic, Former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of European Affairs of Montenegro

Opening accession talks carries significant symbolic and political weight. Once a candidate country fulfills the conditions set by the European Commission, withholding the opening of negotiations becomes indefensible in terms of credibility, consistency, and the EU’s transformative leverage. Moreover, failing to open talks despite fulfilled benchmarks can have profoundly negative consequences for democratic stability, public trust, and reform momentum. North Macedonia remains the clearest example of how prolonged political blockage — unrelated to merit — erodes confidence in the process and strengthens anti-EU narratives.

It is equally important to underline that opening negotiations is largely a technical step; it does not predetermine the pace, substance, or eventual outcome of accession. Politicizing this stage by linking it to bilateral disputes is therefore both unproductive and damaging. Bilateral disputes should be addressed through dialogue, or the new structured bilateral dialogue instrument, rather than being allowed to obstruct accession steps. This model should form a part of the internal reform document that the European Commission intended to publish alongside the November Enlargement Package — a document that should not have been delayed again.

To move beyond blockages, the EU needs to restore a consistent merit-based approach, establish a predictable and credible framework for handling bilateral disputes outside the accession process, and ensure that once benchmarks are met they are not retroactively reopened. Only such a separation can rebuild trust, protect the EU’s credibility, and keep the reform process on track.

Ramadan Ilazi, Head of Research, Kosovar Center for Security Studies, Former Deputy Minister for European integration in Kosovo

Bilateral disputes between candidate countries and individual EU member states can become a major obstacle to the accession process, such as the case of North Macedonia. These disputes are becoming also a headache not only for candidate countries but also for the European Commission. This is because they usually fall outside the acquis and are rooted in political interests and can be weaponized as vetoes. This “vetocracy” risks turning enlargement from a merit-based process into a hostage of national agendas of individual EU Member States. While the EU’s unanimity requirement cannot be easily undone due to existing treaties, both the EU and the candidate countries have some options to prevent blockade. European Council President António Costa has proposed allowing negotiation clusters to open by qualified majority voting, rather than unanimity, which is an acknowledgement that the current system is too vulnerable to obstruction.

For Ukraine, four potential steps are important from my perspective. First, be ready and anticipate, by conducting a comprehensive study of any potential bilateral dispute that you have or may arise with EU member states, and think of innovative ideas to engage those member states, even preemptively. Second, work with the EU to decouple bilateral disputes from the accession process. Ukraine can offer arbitration or mediation to any member state with grievances or issues, shifting disputes to a parallel track. Third, propose mechanisms/forums that seek to reconcile differences and engage constructively. For example, the Berlin Process in the Western Balkans helps defuse tensions, and foster understanding between the region and the EU member states. This would also mean that Ukraine is not acting dismissively towards EU member states issues, but treating them with respect. Fourth, pursue what I would call “operational integration” in parallel to accession, joining EU agencies and mechanisms as an associated partner, such as European Union Cybersecurity Agency (ENISA). Considering rule of law is important for Ukraine, it can seek greater integration in foreign direct investment screening mechanisms, like EU Expert Group and Contact Points network. Ukraine should avoid the North Macedonian scenario, and risk stalemate, but engage proactively with all.

Bojan Maricik, Former Deputy Prime Minister for European Affairs of the Republic of North Macedonia

The bilateral issues between EU Member States and the candidate countries are the greatest obstacles for a strict, fair and effective EU accession process. North Macedonia has paid an extremely high price for the bilateral disputes with the neighbors. After the historic Prespa Agreement with Greece, a new blockade came from Bulgaria that postponed the process, diminished the EU credibility and opened the door for domination of the Eurosceptic political narrative that drowned the EU popular support by 20%. The best answer of a candidate country to a bilateral blockade is to speed-up the reforms, build up the relations with the partner EU Member States and open an-equal footing dialogue with the disputing EU Member state. That is not enough, the EU should also take action and try to build up a parallel mechanism for bilateral dispute settlement within the EU accession negotiations, so the reforms can move unhindered and it will be rewarded by the EU. The bilateral disputes of this kind have to be resolved on a basis of European values, in a fair and credible compromise that preserves the national but not less the European interest. Each other approach only weakens the EU and strengthens its adversaries and their agendas.

Tinatin Akhvlediani, Research Fellow, Center for European Policy Studies, Belgium

Candidate countries cannot bypass member-state vetoes directly, but they can prevent the process from fully stalling by focusing on the reforms required for accelerated EU integration. By implementing these reforms — from rule-of-law and anti-corruption measures to EU acquis alignment and institutional capacity building — candidate countries could make the case for their readiness undeniable. This creates a stronger basis for the EU to build consensus among member states and ultimately secure the unanimous green light needed for the next steps.

This way, even if formal negotiations are temporarily blocked, real progress will continue: reforms will benefit the candidate countries directly, strengthening governance, economic resilience, and institutional capacity. These achievements advance European integration by default, ensuring that when vetoes are eventually lifted, candidate countries can move rapidly toward accession treaties with minimal delays. In this sense, persistent reform and tangible progress are both a safeguard against political deadlock and a demonstration of the candidate countries’ commitment to the European path.

Susan Stewart, Senior Fellow, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), Germany

There is no way to bypass such disputes completely. In fact, the present blockade of Ukraine’s accession process by Hungary has demonstrated that the EU does not currently have the instruments to deal with such a situation, even when the reasons for the blockade are unjustified. Therefore, it is necessary for candidate countries to try to foresee such difficulties and attempt to resolve them on the bilateral level at an early stage. If this is not an option, they should attempt to persuade as many EU member states as possible that they have done all they can to address the dispute, and encourage those member states to join forces in tackling the situation. However, too much attention to such a case gives the offending member state more significance and status than it deserves. Thus at some point it is better to focus on other challenges and return to the blockade once a window of opportunity opens to have it resolved. Candidate countries also need to prepare for the likelihood that certain limitations will be imposed on them in the process of their accession, since the EU will want to avoid new members being able to replicate the behaviour of problematic member states once they have joined the club.

Fjoralba Caka, Former Deputy Minister of Justice of Albania

Bilateral disputes with an EU Member State can block the accession negotiations. The EU Member State may use the negotiation process as leverage to solve bilateral disputes, testing the candidate country’s preparedness and strategic approach. In addressing the dispute, the candidate country should clearly define its strategic national interests, by engaging national experts and stakeholders of different backgrounds, in order to have a well-supported position. Where direct solutions prove difficult, the European Commission can act as a mediator or arbitrator. Alternatively, the candidate country can seek resolution through arbitration mechanisms or international courts, providing legal solutions to historical problems. Communication with citizens is important to signal that EU accession does not undermine domestic interests, or that the current government will not prioritize the first over the second. At the technical level, the candidate country should try to decouple the bilateral disputes from benchmarks, consider phased or parallel solutions, and have a pro-active engagement with the EU Member State. In the midst of turmoil of domestic debates and external pressure, the candidate country should not lose reform momentum in other areas and should engage with the Commission and Member States to ensure that accession negotiations are anchored within the principles of enlargement and merit-based progress.

PDF-version is here.

The material was prepared with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. The material reflects the position of the authors and does not necessarily coincide with the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.