Analytical Report Based on the Online Discussion Organized by the New Europe Center on 6 November 2025.

Prepared by Dmytro Babushko, Junior Analyst, New Europe Center.

Robust security does not boil down to a single “magic guarantee” or formula – it has to be built on a combination of one’s own military capability, stable long-term funding, and a broad network of partnerships. Against the backdrop of an increasingly active negotiation process, the issue of real – rather than declarative – security guarantees for Ukraine is coming to the forefront. The experience of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan shows that real guarantees are the result of sustained political work, institutional decisions, and investments in one’s own defence, rather than ambitious wording in agreements. This is one of the key conclusions of the online discussion “Asian Security Models: Insights for Ukraine’s Defense Future,” organized by the New Europe Center on 6 November 2025. Leading experts from Ukraine, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan took part in the event. The New Europe Center has prepared a short analytical report based on this discussion.

Over the past few years, the New Europe Center has been consistently studying the experience of East Asian countries to understand which models can be useful for defence and deterrence in complex security environments, and how Ukraine can apply this experience. In 2023, the Center published the discussion paper Security Formula “NATO Plus”, which, among other countries’ experiences, analyzed the approaches of South Korea and Taiwan to long-term threat deterrence. In April 2025, the Center’s team prepared a series of infographics on international military missions, including the historical examples of Japan and South Korea, in order to identify key preconditions for a successful military mission for Ukraine. In the same year, the New Europe Center organized a cycle of discussions with leading experts from Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, focused on how Asian countries shape and maintain defence resilience in complex security conditions. These discussions made it possible to compare different approaches – from allied security guarantees to models based on national defence capabilities.

“The Armed Forces of Ukraine are the core of our defence”

Individual components of security guarantees must be provided to Ukraine already now; Ukraine’s security cannot be built on waiting for a ceasefire. Security guarantees must have a practical dimension: financial resources, weapons supplies, joint production, and military exercises. This was one of the key points made by Leonid Litra, Senior Research Fellow at the New Europe Center, who outlined the Ukrainian vision of the topic. After the end of the war, these components must become long-term mechanisms that would make renewed aggression impossible.

A crucial pillar of security for Ukraine is permanent financial support. Financial stability during the war makes it possible to sustain the Armed Forces, supply ammunition, ensure effective air defence, and develop production. Ukraine should receive guarantees of stable funding for at least the next two to three years. The use of frozen Russian assets to create a multi-year fund for supporting Ukraine can demonstrate that Ukraine’s partners are determined to continue backing the fight against the aggressor. This would be a compelling argument for Putin to reconsider his war plans.

Another key aspect of security is people. The Armed Forces of Ukraine are a living security guarantee. Stable support from partners makes it possible to provide proper training and equipment for Ukraine’s million-strong army.

The third pillar is an extensive system of partnerships. Kyiv has already concluded more than 30 security agreements that enable flexible cooperation, taking into account the potential of each partner country. Security agreements must be transformed into real operational mechanisms: joint training, participation of instructors, logistics, repair of damaged equipment, and more. The effectiveness of Ukraine’s future security model largely depends on the United States. Even if the US plays only a partial role and does not deploy troops, its contribution to the supply (or sale) of weapons, intelligence, and logistical support will remain crucial.

“East Asia should learn from Ukraine, not the other way around”

Atsuko Higashino, Professor at the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Tsukuba, questions the very concept of “security guarantees” and how they work in practice. She stresses that what Europe calls guarantees is in fact a set of individual actions – assistance, weapons supplies, political support – that states undertake within the limits of their own capacities. Therefore, such “guarantees” do not always translate into real deterrence of an aggressor. As for the lessons Ukraine can draw from the experience of Asian countries, the professor believes that it is East Asia that should learn from Ukraine what a real stress-test of security guarantees looks like when a state faces full-scale aggression.

In the foreign policy of Japan’s new government, the position on Russia and support for Ukraine will likely remain unchanged. At the same time, this policy will continue to contain internal contradictions. On the one hand, Japan is actively involved in meetings of the “coalition of the willing” and maintains a high level of dialogue with Kyiv. On the other hand, Tokyo remains involved in controversial Russian energy projects (especially Sakhalin-2), effectively placing energy security above resolute foreign-policy decisions. Additionally, in Japanese society, security guarantees for Ukraine are not a priority and have limited public support, even though NATO is trying to bring Japan more deeply into its own security initiatives. Atsuko Higashino emphasized that Japan wants to do more, but its commitments are constrained by constitutional limits and energy dependence.

The professor offered several proposals for East Asian states. First, Japan should consider sending its Self-Defense Forces to conduct demining operations in Ukraine. Second, Japan and South Korea, as participants in the IP4 format (Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand), should make fuller use of their status as NATO partners and launch an intensive dialogue both among themselves and with all IP4 countries together. These states must determine how exactly they can effectively cooperate with the Alliance. Third, it is necessary to strengthen security and strategic dialogue between Europe and East Asia and build a solid US–Europe–East Asia triangle, in which the Europe–East Asia line becomes a priority in order to reduce dependence on a single ally amid doubts about the reliability of American support.

For Ukraine, its partnership with Japan demonstrates that even under constitutional constraints and domestic political challenges, a partner can still play a substantial role in deterring an aggressor. However, energy and economic interests of partners often limit their readiness to take more decisive steps.

The New Europe Center’s analysis of international military missions shows that allied models such as the US-Japan one work when long-term security guarantees are combined with a clearly defined scope of military presence. For Japan, partnership with the US did not remain a temporary mission but evolved into a deterrence system supported by political agreements and a clear mandate. For Ukraine, a useful lesson is that any potential international mission (for example, within a “coalition of the willing”) should not be a temporary episode but must be embedded into the overall security architecture.

“Ukraine needs stronger national defence capabilities”

Kim Youngjun, Professor and Dean of Academic Affairs at the National Security College, Korea National Defense University, and Advisor to the Ministry of National Defense of the Republic of Korea on arms control and verification, suggests looking at the Korean experience through the prism of the instability and fluidity of alliances, as well as through the strengthening of national defence capabilities. He recalled that the conclusion of the bilateral security treaty between the Republic of Korea and the United States was the result of a difficult political and diplomatic process. The determination of President Syngman Rhee made it possible to lay the foundation for today’s strong alliance.

The experience of South Korea confirms the conclusions of the discussion paper Security Formula “NATO Plus”, particularly the analysis of the Korean model prepared by Nataliya Butyrska, an Associate Senior Analyst at the New Europe Center. Initially, the United States offered Seoul not hard security guarantees but political statements and promises of possible assistance. Only after persistent and at times confrontational pressure from Syngman Rhee did the US agree to sign a full-fledged Mutual Defense Treaty. This means that even in South Korea’s case, strong security guarantees were not a gift, but the result of purposeful and difficult diplomatic work with the American side.

After Donald Trump’s return to power in the United States, concerns have grown in the Republic of Korea about a reduction or even a complete withdrawal of the US military contingent from South Korea. Against this backdrop, public demand for a national nuclear capability has increased; around 70% of respondents support the idea of developing nuclear weapons in the ROK. All this shapes South Korea’s current security approach. The Korean strategy now is to preserve and strengthen the security alliance with the US while simultaneously developing new partnerships with NATO countries, Japan, Australia, Ukraine, and others. Moreover, according to the South Korean expert, Seoul must continue to develop its own defence capabilities in order to reduce dependence on the US or any other partners.

The professor from Seoul offered several recommendations for Ukraine: invest in national defence and consider different protection models, including allied nuclear deterrence in Europe and beyond. He also proposed conducting joint naval exercises in the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans together with NATO, Australia, Japan, and South Korea to test different military scenarios and strengthen each other’s presence in security ecosystems. In addition, Professor Kim stresses the importance of long-term friendship and exchange of experience in various dimensions – human, security, cultural, and economic. This would allow Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Ukraine, and European countries to build strong partnerships that do not depend on a single presidential term in Washington.

Foreign observers sometimes refer to the history of the Korean settlement as a model that could allegedly be applied to Ukraine as well. Similar statements about a Korean-style solution are also heard from Russian politicians. However, such commentators usually refer only to one part of the Korean experience (force separation, “freezing”), while ignoring another crucial component: Seoul received – and continues to receive – substantial military assistance from the United States. This is explicitly noted in the Security Formula “NATO Plus” discussion paper, which points out that Ukraine is mostly offered simplified versions of existing systems. Ukraine must understand that references to the Korean model do not automatically mean an equivalent Korean-level security system. It will have to fight separately for what exactly will be written into the text of the arrangements so that guarantees are real rather than declarative.

“Our protection rests on mechanisms, not on formal treaties”

Cathy Fang, Policy Analyst at the National Security and Economic Security Research Program, Research Institute for Democracy, Society, and Emerging Technology, invites us to look at Taiwan’s experience as a model without a formal alliance treaty but with a well-developed system of security mechanisms. She compares the experiences of Ukraine and Taiwan as two countries that are not part of formal military alliances and do not have official “security guarantees” from the United States.

For Taiwan, the basis of its security relationship with the US is the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA), the “Six Assurances,” and a number of annual decisions by Congress (including the Taiwan Enhanced Resilience Act), which provide for multi-year assistance, joint training, and transfers of weaponry. This contrasts with the Ukrainian model, where US support is provided through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative and the ten-year bilateral security agreement between Ukraine and the US signed in 2024. The TRA is US domestic law, while the agreement with Ukraine is an executive-branch document. But in both cases, this is not about a formal defence treaty – rather, a set of legal and political instruments.

Comparing the texts, the expert identifies common elements: the formula of “grave concern” regarding any attempts to change Taiwan’s status or to launch new aggression against Ukraine, and the emphasis on “credible defense and deterrence” – that is, the obligation of the US to provide Taiwan with defence capabilities and to facilitate the maintenance of reliable defence capacity in Ukraine. She also notes that the “Six Assurances” (no end date for arms sales, no prior consultations with Beijing, no US mediation role, no pressure on Taiwan to negotiate with the PRC, etc.) together with the TRA and Congressional decisions provide continuous support to Taiwan without formal recognition of its sovereignty and without the deployment of a US military contingent. The analyst underscores that mechanisms are more important than formal treaties. If a mechanism – comprising legislation, annual funding, regular consultations – works, then a formal agreement is no longer a necessity.

At the same time, as shown by the analysis of the Taiwanese model in the Security Formula “NATO Plus” discussion paper, even detailed mechanisms can contain an element of strategic ambiguity. The US undertakes obligations to supply military assistance but leaves open the question of deploying a military contingent in case of an armed attack by China. For Ukraine, this is a positive lesson: strategic ambiguity can strengthen deterrence by forcing the aggressor to factor in a wider range of potential partner actions.

In addition, Cathy Fang describes another element of Taiwan’s security model – the “silicon shield.” The idea is that Taiwan has become so important in global trade (primarily in semiconductor production) that any military aggression against it would create serious economic problems for most countries on the planet. The analyst also highlights areas of cooperation that Taiwan is developing, taking into account Ukraine’s experience. These are primarily cybersecurity, the protection of telecommunications and undersea cables, as well as drone production, which enables Taiwan to strengthen its role in international supply chains.

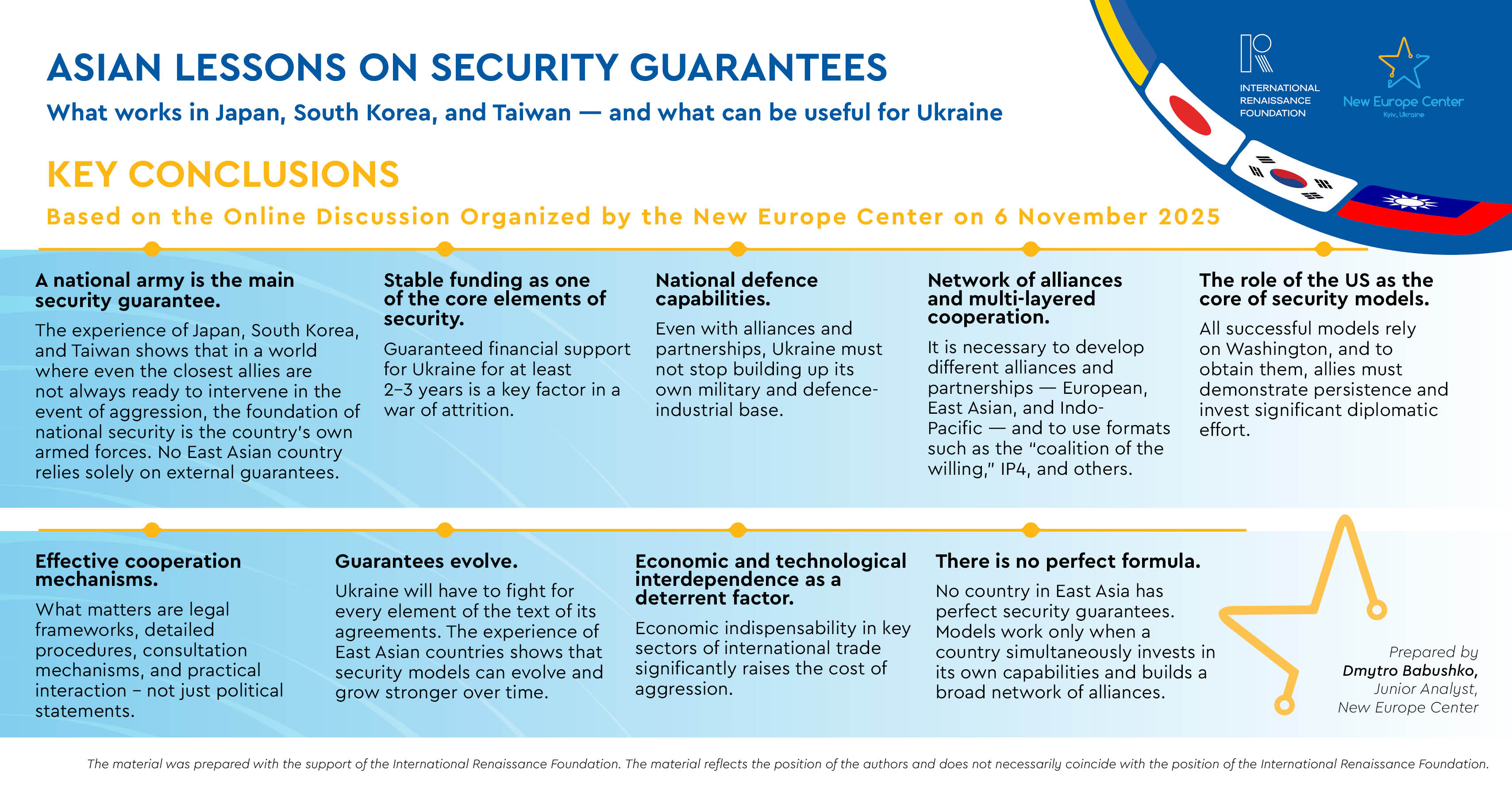

Key Conclusions

A national army is the main security guarantee. The experience of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan shows that in a world where even the closest allies are not always ready to intervene in the event of aggression, the foundation of national security is the country’s own armed forces. No East Asian country relies solely on external guarantees.

Stable funding as one of the core elements of security. Guaranteed financial support for Ukraine for at least 2–3 years is a key factor in a war of attrition.

National defence capabilities. Even with alliances and partnerships, Ukraine must not stop building up its own military and defence-industrial base.

Network of alliances and multi-layered cooperation. It is necessary to develop different alliances and partnerships – European, East Asian, and Indo-Pacific – and to use formats such as the “coalition of the willing,” IP4, and others.

The role of the US as the core of security models. All successful models rely on Washington, and to obtain them, allies must demonstrate persistence and invest significant diplomatic effort.

Effective cooperation mechanisms. What matters are legal frameworks, detailed procedures, consultation mechanisms, and practical interaction – not just political statements.

Guarantees evolve. Ukraine will have to fight for every element of the text of its agreements. The experience of East Asian countries shows that security models can evolve and grow stronger over time.

Economic and technological interdependence as a deterrent factor. Economic indispensability in key sectors of international trade significantly raises the cost of aggression.

There is no perfect formula. No country in East Asia has perfect security guarantees. Models work only when a country simultaneously invests in its own capabilities and builds a broad network of alliances.

Media version was kindly published by Ukrinform.

The material was prepared with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. The material reflects the position of the authors and does not necessarily coincide with the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.