North Korea has decided to provide extensive support for Russian aggression. Sending North Korean soldiers to the battlefield could change South Korea’s approach to helping Ukraine. The New Europe Center has decided to analyse what factors are holding back the South Korean president and his administration from strengthening their support for Ukrainians. Given that the authorities of the Republic of Korea (ROK) have announced a ‘phased steps approach’ to responding to the involvement of North Korean troops in the war, we will explore whether we can expect a change in Seoul’s policy on providing lethal weapons to Kyiv. In this regard, we will pay attention to how South Korean society and the opposition influence the president’s policy and why they oppose military support for Ukraine. Despite a number of security, geopolitical, and domestic factors that significantly limit South Korea’s response to the strengthening of Russian-North Korean cooperation, we will identify the main areas of interaction between Kyiv and Seoul in the context of confronting common security threats.

The Republic of Korea’s (ROK) response to the deployment of North Korean troops

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, South Korea has joined Western sanctions, imposed export restrictions on more than 1,400 types of goods, and actively supported Ukraine by providing financial, humanitarian, technical and non-lethal assistance (bulletproof vests, helmets, demining machines, pickup trucks, mini-excavators, etc.) However, it avoided supplying weapons directly, citing the Law on Foreign Trade, which allows exports of strategic goods only for peaceful purposes. Potential change in this policy has become a threat from the ROK leadership and a kind of deterrent to Russia’s deepening relations with North Korea, especially with regard to the provision of advanced nuclear and missile technologies, and vice versa, Vladimir Putin has repeatedly threatened Seoul with consequences if it starts supplying weapons to Ukraine.

Meanwhile, the DPRK has openly supported Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, has become the largest supplier of weapons to Russia, including shells and missiles, and has now sent units of the Korean People’s Army to directly participate in hostilities – an unprecedented step that the DPRK has taken for the first time in its history. The Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement signed between the DPRK and the Russian Federation on 19 June 2024 and ratified by both sides, which provides for mutual military assistance, laid a long-term foundation for military cooperation between Moscow and Pyongyang.

In response to the information about the deployment of North Korean troops, the Office of the President of ROK said that it will not ignore this issue and will mobilise “every possible asset” in cooperation with the international community. Firstly, a number of multilateral and bilateral consultations were conducted:

- The exchange of information with NATO, the EU and Ukraine on Russian-North Korean relations was accelerated. On 21 October, President Yoon Suk Yeol had a telephone conversation with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte and sent a delegation of representatives of the National Intelligence Service and defence agents to Brussels in order to intensify security cooperation and develop joint responses to Russian-North Korean cooperation through the ROK-Ukraine-NATO line. The parties agreed to quickly complete the process of the Republic of Korea’s accession to the BICES information system used by NATO and to jointly monitor Russia’s possible transfer of sensitive technologies to the DPRK.

- On 25 October, national security advisers from the ROK, the US and Japan – Shin Won-sik, Jake Sullivan and Takeo Akiba – held a trilateral meeting in Washington to discuss the recent deployment of DPRK troops in Russia. They expressed hope that China would play a constructive role in addressing the illegal actions of the DPRK and Russia.

- On 30 October, a UN meeting was held to discuss the deployment of North Korean troops at the initiative of Ukraine, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, South Korea, Slovenia and Malta.

- On 31 October, the deployment of North Korean troops became a main topic at “2+2” US-ROK Foreign and Defence Ministerial Meeting in Washington.

- The direct contacts between Ukraine and ROK became more active. On 29 October, the Presidents of ROK and Ukraine held a telephone conversation, which resulted in an agreement that ROK will send a special envoy to Ukraine to develop joint response measures. After the visit to NATO’s headquarters, a South Korean delegation, which consisted of high level military and intelligence officials, also visited Ukraine. On 27 November, a Ukrainian delegation headed by Defence Minister Rustem Umerov visited Seoul to meet with President Yoon Suk Yeol, Defence Minister Kim Yong-hyun and other senior officials to share intelligence on North Korean troop deployments and seek support for Ukraine’s military efforts. The visit to NATO headquarters was followed by a visit to Ukraine by a South Korean delegation of senior intelligence and military officials.

- On 4 November, Josep Borrell, High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy visited Seoul. Before that, President of the ROK Yoon Suk Yeol held a telephone conversation with the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen.

Secondly, President of South Korea Yoon Suk Yeol declared a ‘phased steps’ approach of responding to cooperation between Russia and North Korea, depending on the DPRK military’s involvement in the war. He assumed the possibility of direct deliveries of weapons and military equipment, especially defence ones, ‘depending on the steps of North Korean soldiers’.

Elements of deterrence

Despite the fact that South Korea signalled about the potential shift in Ukraine’s support policy after the deployment of North Korean troops, Yoon Suk Yeol faces serious resistance inside the South Korean society and from opposition that are afraid of involvement into a proxy-war against DPRK and deterioration of relations with Moscow, which can lead to escalation of the situation on Korean peninsula.

Moreover, on the eve of Defence Minister Rustem Umerov’s visit to Seoul on 27 November, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Rudenko once again threatened the ROK with a break in relations and ‘consequences’ for security if ‘South Korean weapons are used to kill Russian citizens’.

Right now, President Yoon Is forced to focus not only on internal concerns, but also on changes in US policy with Donald Trump coming to power.

Main elements of deterrence that influence on South Korean government position are:

- The policy of the newly elected US President Donald Trump, which is aimed at ending the Russian-Ukrainian war, as well as his previous statements on the topic of stopping sending military aid to Ukraine. This calls into question the appropriateness of providing lethal weapons to Ukraine and creating risks for its relations with Russia if the key security ally will implement other policy. The ROK also draws attention to the situation with the possible reduction of assistance to Ukraine in European countries;

- The prevailing opinion in South Korean political and expert circles is that direct supply of lethal weapons to Ukraine, without going through third countries, including the United States, will dramatically change the security dynamics on the Korean peninsula. There are fears that in this case, Moscow will have no restrictions on the provision of critical nuclear and missile technologies to the DPRK;

- The position of the main opposition democratic party, Toburo, which has a majority in parliament and opposes the provision of lethal weapons to Ukraine and also threatens President with impeachment, in case this decision will be adopted bypassing parliament;

- The country’s internal political crisis, as a result of which opposition forces resist the president’s foreign and domestic policy initiatives;

- Public sentiment. According to a public opinion poll conducted in late October 2024 by Gallup Korea on behalf of JoongAng Ilbo, 64% of the ROK’s residents oppose the supply of weapons to Ukraine, while 28% are in favour and 8% do not know or refused to answer. The survey was conducted after the country’s president said that South Korea may reconsider its position on providing lethal assistance.

According to the survey, security is not a priority among citizens’ requests for the President’s activities for the second half of his term. The issues of greatest concern to respondents are as follows: economic recovery – 21%, improvement of citizens’ welfare and stabilisation of inflation – 16%, strengthening national defence and security – 5%, and resolving issues around the first lady – 5%. [1] As we can see, national security is on the same level as the scandals surrounding the president’s wife (she is accused of manipulating stock prices, receiving a luxury handbag as a gift from a Korean-American pastor, and influencing appointments to high positions. The Toburo Democratic Party initiated the appointment of a special prosecutor to investigate these facts, but the president vetoed the opposition bill).

In regard to such factors, the South Korean authorities continue to have a cautious position and promised to determine a level of support to Ukraine, including sending lethal weapons, depending on ‘the scale of military cooperation between Russia and North Korea’. Such definition lacks specifics, thus it gives possibilities to manoeuvre.

Meanwhile, an analysis of statements by representatives of the South Korean government suggests that South Korea continues to focus on the previously drawn ‘red lines’: Moscow’s transfer of advanced military nuclear and missile technologies to North Korea, including atmospheric reentry technologies, a re-entry vehicle technology, multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), reconnaissance satellites, and nuclear submarines.

Opposition resistance

One of the important steps in Seoul’s response to Russia-North Korea cooperation was an announcement of the intention to send a monitoring group to Ukraine to analyse North Korea’s military activities on the battlefield, consult with the Ukrainian side, and participate in the interrogation of captured North Korean military personnel. The ROK Defence Minister noted that the monitoring group is not a military unit and will consist of a small number of military and intelligence personnel who will be in Ukraine for a short-term visit. The deployment of such a group will be based on Seoul’s need to obtain information related to the country’s security, not at the request of the UN or Ukraine. At the same time, according to official information, the possibility of sending units of the ROK army to Ukraine is not being considered.

It should be noted that the deployment of the monitoring group also met with serious opposition from the leading opposition democratic party Toburo, which threatened to pass a motion of no confidence to the Minister of Defence. Officially, the opposition refers to Article 60 of the Constitution, according to which the National Assembly has the right to give consent to the deployment of armed forces to foreign countries. However, the Minister of Defence states that according to the current directives of the Ministry on the deployment of the armed forces abroad, he has the right to send a small group of uniformed personnel to collect and obtain information.

The opposition is attempting to limit the government’s actions in two ways with regard to sending the monitoring team: it is preparing a submission to the Constitutional Court to overturn the Defence Ministry’s directives, and it is seeking to amend three laws to close loopholes in the legislation that allow the executive to make military supplies abroad without parliamentary approval, fearing that the president will use them to provide weapons to Ukraine.

The Law on Military Supply Management allows the Minister of Defence to transfer supplies to foreign governments for free or for profit without parliamentary approval, provided that the exports do not harm the ROK’s own military needs. Similarly, the Law on Defence Acquisitions and Programmes contains no restrictions on sending defence exports to conflict zones. However, the opposition party insists that lethal aid to Ukraine is contrary to ‘peaceful purposes’ and poses a risk to the ROK’s national security, and that sending military supplies through third countries is contrary to its own military needs, given the technical state of the war with the DPRK. This position of the Democratic Party is a reflection of the deep general disagreements between the ruling and opposition parties – mutual accusations and political struggle slow down the process of solving domestic problems and seriously affect the development of a common position on foreign policy. While Yoon Suk Yeol is trying to expand the country’s foreign policy profile beyond the Korean Peninsula and position the ROK as a ‘global pivotal state’, the opposition party insists on continuing the traditional foreign policy line of seeking a peaceful dialogue with North Korea and balanced relations with Russia. The opposition believes that supporting Ukraine, in particular with weapons, threatens the security of the Republic of Korea, damages relations with Moscow (including economic relations), and creates a risk of being involved in a foreign conflict. So, despite that there are loopholes[2] in the ROK’s legislation that may allow sending Ukraine lethal weapons, under the pressure of geopolitical, security and internal issues, the President rejected Ukraine’s military support requests, who have asked numerous times since the beginning of full-scale invasion.

What weapons can South Korea send to Ukraine?

Following the deployment of North Korean troops, the Ukrainian side again requested arms support from the South Korean government, sending an official letter to the Ministry of Defence and requesting it at a recent meeting at NATO headquarters. In an interview with the South Korean newspaper The Dong-A Ilbo, Ukraine’s Ambassador to the Republic of Korea, Dmytro Ponomarenko, said that the Ukrainian side had submitted its priority arms needs to the Korean government. Firstly, we are talking about defence systems: air defence systems, radars, electronic warfare systems, and drone defence systems. [3]

Ukraine has also provided a list of urgent needs for the defence of its territory, including 155 mm shells, MRLS systems, artillery systems, armoured vehicles and tanks. Given its internal reservations, the Ukrainian government is proposing that Seoul consider the provision of defence equipment on a humanitarian basis, stressing that sending defensive munitions is not an aid to war, but an action aimed at achieving peace.

ROK’s military industry complex manufactures almost every piece of weaponry and military equipment, using new Western technologies, which in turn makes it compatible with NATO weapons. In recent times, old foreign weapons and licensed military equipment are being actively replaced by new pieces of their own production. So, ROK could have provided a number of useful equipment for Ukraine:

- It has 3.4 million 105-mm shells in its warehouses, which were once transferred under the US WRSA-R programme. Plans to gradually decommission 200 K105 artillery systems into reserve status are creating a large surplus of 105-mm shells[4];

- stockpiles of Hawk, Mistral, and Igla air defence missiles, which have been replaced by domestic models;

- Soviet equipment – T80U tanks, BMP-3, BTR-80, Igla-1 MANPADS, Metis MANPADS in good condition, which were received from Russia as part of the repayment of the debt inherited from the USSR;

- US weapons that were once provided to the Republic of Korea under military cooperation programmes – air defence systems and missiles, US armoured vehicles, M113, 155-mm and 105-mm self-propelled artillery, tanks, etc [5].

Korea’s defence industry has succeeded thanks to active arms exports, flexible terms and co-production, as well as consistent government support. The President of the Republic of Korea has an ambitious plan to make the country the fourth largest arms exporter in the world by 2027. It should be noted that the growth in arms exports by more than 70% from 2018 to 2022 was due to contracts with European countries, including Poland ($22 billion) and Romania ($920 million), which filled their military warehouses with new South Korean models after the transfer of their weapons to Ukraine.

Ukraine’s army needs Korean countermeasures to counter the weapons coming from the DPRK to Russia, especially as the range of weapons tends to expand. For example, South Korea’s K239 Chunmoo missile systems would help the Ukrainian army counter the 170-mm M-1989 Koksan[6] self-propelled artillery systems that North Korea has begun supplying to Russia, and the laser weapons that Hanwha Aerospace, which is the first in the world to mass-produce, would be an inexpensive and effective means of fighting UAVs. For South Korea, this would provide an opportunity to increase the potential of its weapons, given that Pyongyang is conducting practical testing and improving its weapons in a war situation.

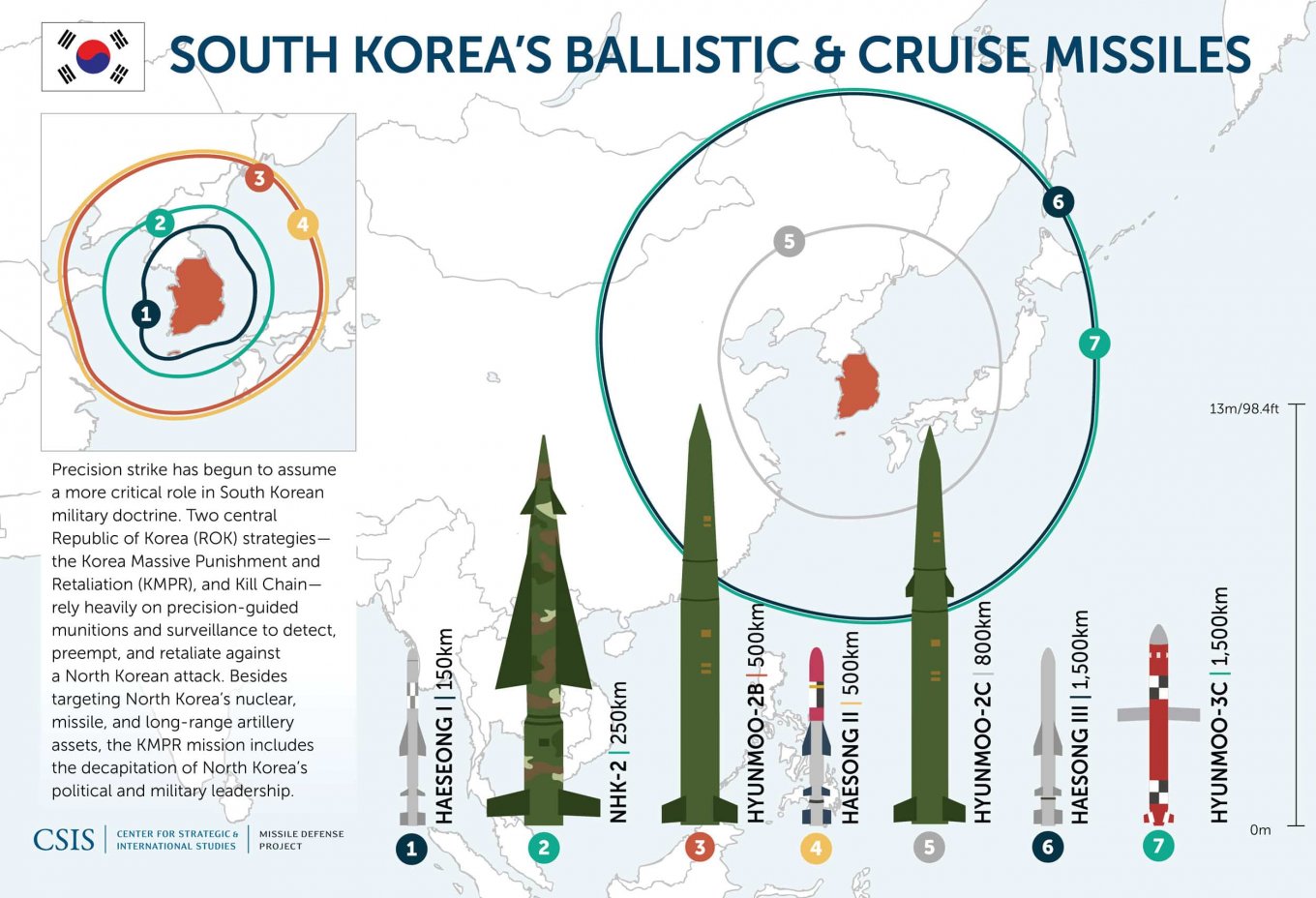

South Korea also manufactures missiles that can strengthen Ukrainian armed forces on the battlefield.

Defence Express identifies three types of South Korean tactical missiles that could help destroy ground targets [7]:

The first option is the KTSSM-II, essentially the South Korean equivalent of the ATACMS, which is to be launched from the K239 Chunmoo missile system.

The second option is the Hyunmoo-2 family of tactical ballistic missiles, which visually resemble the Russian Iskander.

The third option is the Hyunmoo-3 land-launched cruise missile, which is similar in function to the Russian Iskander-K.

Under pressure from the United States and other Western countries, South Korea supplied Ukraine with weapons indirectly through third countries, including the United States. For example, it transferred 550,000 155-mm shells to the US to replace the ammunition it had sent to Ukraine. Thanks to this scheme, the ROK’s indirect contribution to the supply of artillery ammunition was greater than that of all European countries combined. In addition, South Korea allowed the export of its weapon components to Ukraine, which were part of the Polish Krab howitzers. In this way, ways were found to avoid negative consequences for both South Korea and President Yoon Suk Yeol personally. However, Ukraine’s attempts to obtain other types of South Korean weapons through contracting and transfers through third countries were blocked because they became known to Russia and stopped under its pressure.

At the same time, Seoul’s cautious approach has significantly limited South Korea’s military support for Ukraine, and allowed Putin, on the one hand, to skilfully put pressure on the weaknesses of the South Korean authorities, and on the other hand, to gradually change the status quo on the Korean Peninsula, drawing Pyongyang into his military adventure.

Conclusions and recommendations

Deployment of North Korean troops in the European continent requires a more active involvement of Seoul to support Ukraine, as it has serious repercussions to South Korea itself. Such action would have demonstrated South Korea as an even stronger partner for the EU and NATO in Asia, which could have, from its side, counted on the same support from European countries in case of a conflict on the Korean peninsula.

Seoul understands this, but the election of Donald Trump only reinforces precautions even from conservative part of South Korea’s politics on the topic of increasing support to Ukraine, especially providing lethal weapons. South Korea traditionally relies on the United States when it comes to foreign affairs. Accordingly, the government carefully thinks about the steps that could go against the politics of its main ally and create risks for national security of ROK. Apart from that, because of the fragmentation of South Korean political elites and society in general, South Korea lacks a common vision of a strategy to counter geopolitical and security challenges that have increased due to the DPRK’s involvement in the war on the side of Russia, which makes it impossible to act proactively or at least counter them in response.

ROK authorities are trying to involve the international community in a joint countering of Russia-North Korea security cooperation, however, the strategy chosen by the West and South Korea separately to avoid escalation in their response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine stimulated the dynamics of deepening relations between Russia and the DPRK. Thus, repeated threats to provide lethal weapons to Ukraine, which were never implemented, only reinforced Putin and Kim Jong-un’s belief that their actions would go unpunished. Without a common strategy of aggressive deterrence, which includes providing Ukraine with sufficient weapons and permission to hit military targets with long-range weapons, North Korea’s involvement in the war will only grow.

Despite present elements of deterrence, Ukraine should continue an active dialogue with South Korea in order to resist a military alliance between Russia and North Korea, which brings security threats to both countries, and also to encourage South Korean authorities to have a stronger support of Kyiv. Both countries should work on:

- Increasing international pressure and introducing new sanctions against Russia and the DPRK for military cooperation. Work to involve more countries in monitoring sanctions against North Korea through the newly established Monitoring Team (MSMT);

- Initiating international measures to counter military cooperation between Russia and the DPRK, including the possibility of quarantine, inspections, and blockade of ports through which the main arms traffic goes, for violation of UN sanctions;

- Intensifying political cooperation, consultations, and intelligence sharing within NATO. The Republic of Korea is involved in a number of joint projects with NATO to support Ukraine in the areas of military healthcare, cyber defence, countering disinformation, and technologies such as artificial intelligence;

- Strengthening secondary sanctions, export controls and sanctions compliance monitoring on high-tech, military and dual-use goods – critical components that enter Russia and the DPRK through third countries and are used in the manufacture of weapons;

- Conducting joint psychological and information operations against North Korean soldiers to weaken the North Korean army’s involvement in military actions against Ukraine.

In parallel with the fact that Ukrainian authorities should continue to work on possible ways to receive South Korean weapons, the government should also try to involve investments into joint weapons production in Ukraine. It is also important to convince South Korean partners to join the G7 Declaration which was adopted at NATO Vilnius Summit, and sign a bilateral agreement in the security area. The Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement between Russia and DPRK, which is a foundation for long-term cooperation, in the military sphere in particular, brings a common threat for ROK and Ukraine, thus demands to deepen political, diplomatic, security, economical and cultural cooperation. A way to achieve this new level of cooperation between ROK and Ukraine could be a bilateral security agreement.

Strengthening Ukraine’s’ positions in South Korean political and social areas require:

- further close political cooperation at the highest and diplomatic levels

- deepening inter-parliamentary cooperation

- appointment of a special military attaché to work with the relevant authorities in the military sector

- close cooperation between the relevant security, defence and intelligence agencies to obtain the necessary information and coordinate actions

- horizontal interaction between the defence and military companies of both countries to create pressure on the political decisions of the government and parliament of the ROK by local defence companies

- increasing information presence through the involvement of Korean journalists in covering events in Ukraine and engaging Ukrainian experts and journalists in writing materials and interviews for leading South Korean media (KBS, The Korea Times, The Korea Herald, The Chosun Ilbo, The Dong-A Ilbo, Korea JoongAng Daily)

- strengthening academic cooperation and greater involvement of international experts from Ukraine in events, conferences, roundtables organised by Korean universities and think tanks

- Increasing the presence of Ukrainian artists, performers, and cultural figures serves as a counterbalance to Russian cultural expansion, which Moscow actively promotes. In each case, the Ukrainian embassy and community must make significant efforts to disrupt the tours of well-known Putin supporters in the Republic of Korea.

Despite Seoul’s cautious position right now, caused by a number of internal and external factors, general global turbulence and risk of increasing tensions on the Korean peninsula and Asian region in general opens an unprecedented window of opportunities to deepen the cooperation between Ukraine and South Korea. A window Ukraine should definitely use.

PDF-version is available here.

The material prepared with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. The material reflects the position of the authors and does not necessarily coincide with the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.

_________________________________________________________________________

[1] CHO JUNG-WOO Two-thirds of Koreans oppose sending weapons to Ukraine, poll suggests Korea JoongAng Daily: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/2024-11-04/national/defense/Twothirds-of-Koreans-oppose-sending-weapons-to-Ukraine-poll-suggests/2170086

[2] Jeongmin Kim Joon Ha Park Yoon’s Ukraine strategy confronts opposition push to restrict weapons exports KOREAPRO: https://koreapro.org/2024/11/yoons-ukraine-strategy-confronts-opposition-push-to-restrict-weapons-exports/

[3] [단독]주한 우크라 대사 “한국에 무기 지원 요청”… 종전협정 가능성엔 “갈등 동결은 해결책 아냐”, 동아일보: https://n.news.naver.com/article/020/0003597503?type=journalists

[4] South Korea Has 3.4 Million 105mm Artillery Shells, Everyone Would Benefit if Some Went to Ukraine, Defense Express: https://en.defence-ua.com/industries/south_korea_has_34_million_105mm_artillery_shells_everyone_would_benefit_if_some_went_to_ukraine-9956.html

[5] ILLIA KABACHYNSKYI South Korea Is A Major Arms Supplier. What Equipment Can Ukraine Receive? United24Media:https://united24media.com/war-in-ukraine/south-korea-is-a-major-arms-supplier-what-equipment-can-ukraine-receive-897

[6] What weapons can counter North Korean 170-mm self-propelled howitzers M-1989 Koksan that Russian army received? Defense Expess: https://defence-ua.com/news/jakim_ozbrojennjam_mozhna_borotis_proti_170_mm_sau_m_1989_koksan_vid_kndr_jaki_pochala_otrimuvati_armiji_rf-17186.html

[7] If the DPRK sends over 12,000 troops to Russia, what missiles should we request for the AFU from South Korea? Defense Expess:https://defence-ua.com/weapon_and_tech/raz_kndr_posilaje_azh_12_tisjach_vijsk_dlja_rf_to_jaki_raketi_dlja_zsu_varto_prositi_v_pivdennoji_koreji-16932.html