PDF-version is aviable here.

Media-version of ananalytical commentary is kindly published by Euromaidan Press.

‘Escalation’ has become one of the most used words in Western political and diplomatic circles over the two years and nine months of Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine. ‘Won’t this increase the threat of nuclear war?’ was the question US President Joseph Biden allegedly asked his team every time he made a decision to send weapons to Ukraine. The caution and fear of Western politicians will go down in history under the mysteriously sophisticated term ‘escalation management’. The fear of a Russian strike has reached pathological depths. Can we expect a psychological shift in the West’s approach in the near future? Especially in the context of the new US Administration. Tempered by constant Western ‘no’s’, Ukraine must be prepared for the worst manifestations of ‘escalation management’, but at the same time, it must once again focus on patiently explaining to the Trump Administration why a policy shackled by fears of Putin’s Russia ultimately provokes an even bigger war. Ukraine and our like-minded partners are faced with the task of helping the new US leadership to move from the policy of ‘escalation management’ to the best practices of ‘escalation control’ that prevailed during the Cold War.

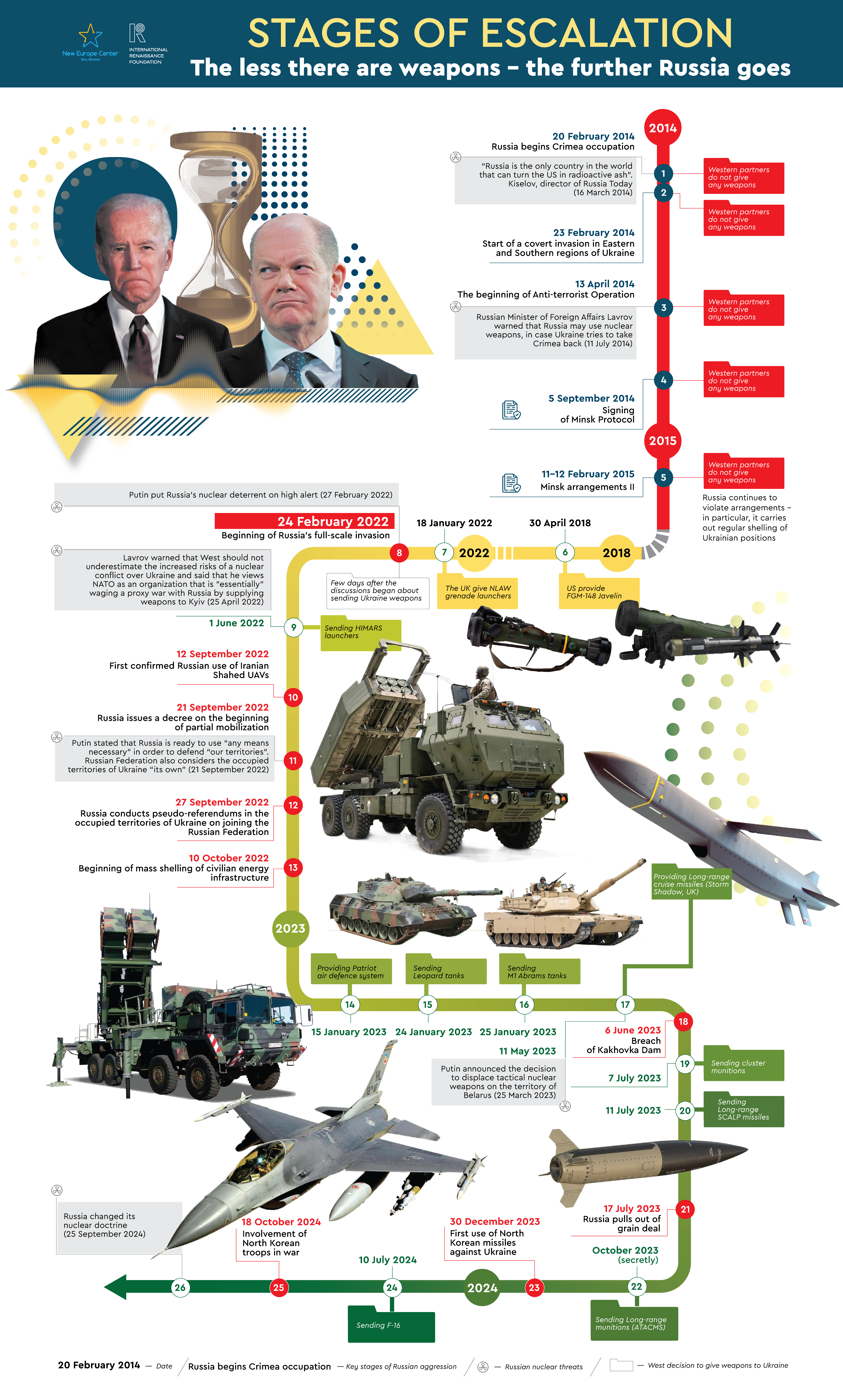

The New Europe Center has prepared an analytical commentary and created an infographic that clearly supports the main conclusion of the policy study: caution and attempts to avoid escalation ultimately lead to greater escalation of Russian aggression and contribute to the transformation of a regional conflict into a global one, with China, Iran, and North Korea becoming increasingly involved in Russia’s military efforts.

EVOLUTION OF FEAR

‘Escalation management’ is a phrase that claims to be a concise definition and assessment of the foreign policy approaches of the United States and its allies in countering Russian aggression. Historically, the United States’ behaviour in the international arena has fluctuated between two extreme positions – isolationism and internationalism. Ukraine was unlucky in this regard, as at the very time when it needed decisive and large-scale assistance, the foreign policy pendulum of Washington swung towards a decline of activities on the global stage. The US de-escalation rhetoric, which aimed to persuade global adversaries to resolve conflicts diplomatically, has had the opposite effect – a united effort by the anti-American axis of evil: Russia, North Korea, Iran, and China.

During the Cold War, the US strategic vocabulary was based more on the concept of ‘escalation control’ – to some extent, the exact opposite of ‘escalation management’, which the US has begun to prioritise in recent years[1]. The United States defined ‘escalation control’ as the ability to dictate the pace of crises, when the enemy was forced into conditions where it had to think about how to respond and how to react. The most famous example is the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when the Kennedy administration threatened to launch a ‘full retaliatory response’ to the USSR’s aggressive actions[2]. Another good example is the Truman Doctrine, which formulated a policy of ‘containment’, aimed to limit the ability of the USSR and its satellites to spread the ideas of communism and establish pro-Moscow regimes around the world. The first serious test of this policy was during the Korean War (1950-1953), when the United States engaged in an active military and political campaign to counter the communist regime of Kim Il Sung, supported by Moscow.

Compare one of the key messages of Truman and Kennedy, who made numerous arguments for the need for a proactive policy to counter the expansionist policies of the USSR. Kennedy, in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis, emphasised in his address: ‘The 1930’s taught us a clear lesson: aggressive conduct, if allowed to go unchecked and unchallenged, ultimately leads to war.’[3] In his memoirs in 1956, Truman recalled the communist offensive against South Korea: ‘If this were allowed to go unchallenged it would mean a third world war, just as similar incidents had brought on the Second World War’.[4] It is ironic that both Truman and Kennedy were representatives of the Democratic Party, and that Biden, whose administration adopted the principle of de-escalation to avoid escalation, ended up with even greater escalation and discredit to the entire foreign policy strategy.

In the United States, the policy of ‘escalation management’ seems to be considered a success: the key arguments are based on two theses. The first is that a nuclear war did not happen, Russia did not attack any Western country, and World War III was avoided. Second: Ukraine did not lose – Western support was an important contribution to the preservation of Ukrainian statehood, and thus to the disruption of Russia’s original plans.

In a simplified form, the US foreign policy to resolve crises caused by global adversaries over the past 70 years can be divided into three stages. The first was during the Cold War, when the West resorted to methods of ‘escalation control’ and deterrence – the US was not afraid to raise the stakes, believing that this was the only way to stop the USSR. The second falls on the period after the collapse of the USSR, when the United States began to take advantage of the ‘unipolar moment’ – as a global superpower, it resolves international crises either unilaterally or through the formation of coalitions, sometimes bypassing the prescriptions of international organisations[5]. The third period coincides with the coming to power of Barack Obama, who partly contributed to the growth of new threats. The reset of relations with Russia in 2009 sent a clear signal to the anti-American camp that a window of opportunity was opening due to the West’s weak response to the adventurism of other actors (the Russian aggression against Georgia was a test case). A little earlier, Western European countries (Germany and France) sent such a signal by blocking the NATO Membership Action Plan for Ukraine and Georgia. The USA under Barack Obama’s administration and Germany during Angela Merkel’s tenure, unwittingly, set a trend that ended in a fiasco, as it allowed anti-democratic forces to strengthen their positions and added chaos to international relations.

Joseph Biden continued a policy of limited, cautious response, which was fully exploited by the US’s old rivals. The Russian leadership was so confident in impunity and permissiveness that it did not hesitate to launch a large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The topic of a possible escalation, a nuclear strike by Russia, has become one of the key factors affecting the pace and scope of US assistance to Ukrainians. During discussions on arms supplies to Ukraine, Biden allegedly often asked the same question: ‘Won’t this increase the threat of nuclear war?’[6]

Of course, Russia was aware of the fears of the US administration, and therefore regularly resorted to new nuclear threats. Anyone who has ever had the opportunity to talk to foreign politicians or diplomats about arms supplies to Ukraine have heard a more or less standard set of excuses:

- ‘It takes time to train Ukrainian soldiers.’ (This argument is used very rarely any more, given the protracted nature of the war).‘

- You have problems with mobilisation, so there is no one to provide weapons to.’ (Although the problem with mobilisation is, in particular, a consequence of weak, slow support).

- ‘Ukrainians should take into account public sentiment in other countries that oppose the provision of weapons.’ (This was inevitable, which is why Ukraine insisted on large-scale military support before the invasion and especially in the first months of the invasion, when the initiative was on the side of the Ukrainians).

- ‘Our country has already reached a critical level of weapons in its warehouses.’ During discussions on arms supplies to Ukraine, Biden allegedly often asked the same question:

- ‘This particular weapon will not change the course of the war.’ (In such circumstances, there should have been no reservations about its transfer to Ukraine).

The most popular excuse, however, is the fear of provoking a more serious reaction from Russia (for example, a possible attack on a NATO member state or a nuclear attack on Ukraine or another country that supports Ukraine). This is where the long-recognisable phrase ‘escalation management’ (managing risks that could lead to a new round of Russian aggression) comes in, which has essentially masked the West’s inability to make bold security decisions.

A paradox: The United States and Germany are champions in supporting Ukraine, but they are also record holders in trying to appease Vladimir Putin by ignoring the most important decisions for Ukraine.

Election period is an additional reason that forces American and German leaders to take into consideration the public mood even more carefully. If Biden tried to prove to the Americans that he didn’t allow the World War III, Scholz came back to his old practice to be the standard of cautiousness (how to help Ukraine so that I won’t look weak, as well as I won’t lose support of the part of German electorate that is infected with Russian narratives). Anti-war and pro-Russian sentiment in Germany became a fertile ground for new political powers – for example, Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance that advocate for Ukraine’s capitulation and follow typical anti-American rhetoric. Scholz’s and Social Democrats efforts to avoid further flow of voters to the radical left leads to Germany’s weaker position on the international arena in general and when we talk about support to Ukraine in particular.

DE-ESCALATION THAT LEADS TO ESCALATION

In this background, the voices of those whom our New Europe Centre refers to as the ‘Coalition of Resolute’ – partners who are in favour of more decisive assistance to Ukraine – have become increasingly heard in foreign media. Right now, these are mainly politicians, advisers, experts, and journalists (many of whom have considerable influence on decision-making in the highest offices of the world). For obvious reasons, such articles are often non-public. The New Europe Center has recently had the opportunity to read several important documents of a recommendatory nature to key Western governments on changing approaches to responding to Russian aggression. There is considerable evidence that some advisers to political leaders who have so far taken a more cautious stance may be reconsidering their views. This is especially true of Joseph Biden’s circle, which is currently making efforts to build a positive legacy for the American leader in the field of international security. Simply put: how to prevent the weak response to Russia’s aggression from becoming another foreign policy failure of the Biden era, on a par with the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan – that is, whether it will be possible to change this perception at the last minute.

There were certain signs that Western governments were preparing to adjust their support for our country. For example, the US administration has stepped up its public rhetoric, talking about Ukraine’s victory. In the middle of September there was information that the US and UK will allow deep strokes into Russia. Intensive contacts between Washington and London with Kyiv, bilateral negotiations between Americans and British at the highest level on this topic gave a hope for some optimism (in the end such a decision was made after the elections in the US).

“Biden’s ‘escalation management’ in Ukraine makes the West less safe”[7], “How to win in Ukraine: pour it on and don’t worry about escalation”[8], “Russia is probing NATO with drone and missile attacks. Ignoring them is a dangerous choice“[9]. These are just a few of the analytical pieces that have appeared recently in leading Western media criticising the West’s failed approaches. The main point of these comments is that the more the West tries to de-escalate the conflict with Russia, the greater the escalation becomes. The West’s indecision is perceived by Russia as weakness. Slow support for Ukraine is also seen as evidence of fear of Moscow.

The New Europe Center has developed a timeline (see infographic) to show how Russian aggression has evolved – the key stages of this aggression occurred precisely when the West was dragging its feet, when Russia could have been stopped at the start: partners either did not provide weapons at all or provided them slowly, in small quantities, and with the wrong types of weapons that could have made a difference on the battlefield. At the same time, Moscow’s nuclear threats were a constant companion to Russian aggression: Russia has abused nuclear blackmail so often that the West should have become accustomed to it and ignored it. However, ‘nuclear’ fears in the West still influence support for Ukraine. Observers of US policy towards Ukraine have commented that even if there is a 1% risk that Russia could escalate, the US will not cross any imaginary red lines.

Russia’s ‘escalate to de-escalate’ approach has proved more effective than the West’s de-escalation approach. The slowness of Western countries allowed Russia to adapt, gain strength, and enlist the support of other dictatorships. In fact, it is the West that should have learnt the fundamental lessons from the failed de-escalation policy. However, it was Russia that learnt the most successfully: it increased its arms production and worked to build a loyal circle of allies who support Moscow without fear of escalation. Most importantly, Russia has realised that it has the most effective weapon at its disposal – bluffing: it requires no resources, but works reliably: you don’t need to fire missiles, you just need to promise to fire them.

It is also impossible to call Western policy completely static. The same graphic by the New Europe Center shows that, in the end, the United States, Britain, Germany, and France crossed ‘red lines’ (whether it concerns the Humvees, Patriots, or even more so the Leopards, Abrams tanks, and F-16 fighters). One might say: but the West’s raising of the stakes has not led to Russia being forced to peace either… The problem, however, is not only the transfer of certain weapons, but also their timeliness and volume. If we act slowly and impose a lot of restrictions, then, as we have seen, this approach will also do little to help the hopes for peace. The transfer of weapons was often accompanied by the words that they should be used for defensive purposes, only on the territory of Ukraine, etc.

The West became hostage to the policy that Ukraine has the right to defend itself. As soon as Kyiv started crossing the “red lines”, it was immediately followed by alarmed calls from its partners to stop ‘escalating steps’. This was especially noticeable during the first stage of Ukrainian strikes on Russian refineries. To date, the West seems to have failed to realise that it is the strategy of defensive warfare that has become one of the key factors in the protracted nature of the war, and that it is Ukraine, not the aggressor, that is forced to suffer extraordinary losses.

Western partners constantly emphasise the need to strengthen Ukraine’s air defence, but are reluctant to talk about Ukraine’s right to respond militarily on Russian territory, retaliate, or mirror. Yet it is quite obvious that even the most effective air defence cannot fully protect Ukraine (to which we should add that the West has consistently broken promises to transfer the necessary systems). This led to extraordinary losses in Ukraine, tens of thousands of victims – the aggressor could attack when, how and how many times it wanted, without fear of retaliation. The West is forced to invest billions of dollars to provide Ukraine with reliable air defence systems, while Russia can get by with much less to manufacture and purchase missiles and drones that it uses to attack Ukraine. Defence will always be more expensive than offence. As a result, most Russians are not actually aware that their country is at war. Instead, in Western countries, the fear of war escalation has become one of the dominant issues in electoral discourses – fatigue from the war, which ordinary Germans or Americans have only seen on TV, affects political sympathies and the emergence of new politicians with an anti-war, pro-Russian agenda. The strategy of defensive war chosen by the West has led to social exhaustion in Ukraine and partner countries, but not in the aggressor country.

LAST CHANCE

The fact that the world’s media have recently begun to criticise Western governments for their indecision, albeit with considerable delay, indicates a certain psychological shift. Of course, this shift in itself means nothing, as it is overlapped with numerous factors, obstacles that create a huge gap between these breakthrough analytical recommendations and the decisions of politicians, who increasingly listen not to the rationale of experts but to the emotions of a part of the population that advocates appeasement of the aggressor. No matter how persuasive the voices of analysts and advisers may be, they cannot compete with the public voice, which is vulnerable to the populist promises of political speculators.

Should we give up? If Ukraine had accepted all Western approaches based on the fear of escalation, it would probably have been fully occupied by Russia long ago. The preservation of Ukraine’s statehood and Russia’s significant losses are the result of our country’s more risky, proactive behaviour. Whether it is the provision of more serious types of weapons or Ukraine’s accession negotiations with the EU, all of this at one stage looked like a fantasy. However, large-scale criticism and convincing arguments by Ukrainian diplomats and its partners led to appropriate changes.

Russia’s raising of the stakes (in particular, the involvement of DPRK troops), the intensity of hostilities, and the diplomatic efforts of the Ukrainian authorities may indirectly indicate that both sides are preparing for a certain turning point. And although neither side declares this publicly, it is clear that all eyes are on the United States. Joseph Biden has the opportunity to present bold decisions that could well overcome the excessive caution of previous years. First and foremost, he could invite Ukraine to join NATO, which would require US diplomatic talents to convince several opponents in the Alliance to support such a decision. By and large, the West has the last chance to at least partially correct its previous shortcomings. In the future, the situation will become even less favourable for ambitious decisions both in the international arena and within partner countries.

Obviously, there is a problem: no matter how much the Biden administration tries to adjust its long-standing course now, these changes may not be enough. Not to mention that they will come too late. Another challenge is that the new decisions could backfire, as President Trump has sent some signals that he will pursue diametrically opposed policies towards Ukraine and Russia (at least initially). The change of power in the United States and the election period in Germany create a kind of ‘grey zone’, uncertainty, which plays into Russia’s hands even more. Moscow understands that transatlantic unity is probably on its last breath, and it can also mean that the united support of Ukraine from the US and the EU will crumble.

Ukraine has every reason to consider the current stage in the fight against Russian aggression to be the most vulnerable. The room for manoeuvre and work with the decision-makers from key partner countries has narrowed tremendously. In the case of the United States, the key figures who will implement the new president’s foreign policy vision are not fully known. Donald Trump also has repeatedly made it clear in public that his vision of ending the war with Russia differs from that of the current US administration. In the case of Germany, the situation is even worse: the country is entering a period of electoral struggle, and then a phase of coalition forming. The speed of assistance has always been a weakness of Germany’s response to Russian aggression. Now we may witness even more dramatic handling of the urgency and pace of decision-making by our partners. Some of the decisions of the new US administration may be too quick, without proper discussion with Ukraine and other partners, which may sometimes be in Russia’s interests. Germany’s decisions may be put on hold altogether.

In this context, the Ukrainian authorities need to act even more creatively, with a subtle but persistent approach. After all, mistakes or slowness in the decisions of partners has been a problem that Ukraine has been dealing with since the first days of Russian aggression. The new administration’s attempts to return the conflict to the diplomatic route may be somewhat reminiscent of similar efforts by Volodymyr Zelenskyy in the first months of his presidency to find approaches to resume dialogue with Vladimir Putin. Perhaps in this sense, it may be even easier for the President of Ukraine to find common ground with Donald Trump, as the Ukrainian leader is able to explain the evolution of his own assessment of the Russian threat – the path from belief in the power of words to understanding the importance of the power of arms. This is the path from unilateral concessions to the realisation that only coercive policies can ‘appease’ Putin.

- ‘Coalition of Resolute’. Engagement of countries that advocate for more decisive support for Ukraine should be carried out on all fronts – political, diplomatic, expert, and media. Whatever the critical voices about the unrealistic expectations of Ukraine, the advocacy work should be as intense as possible. The goals are clear: an invitation to join NATO, air defence shield over part of Ukraine, lifting of all restrictions on the use of foreign weapons, and development of a mechanism for the deployment of foreign troops. For more details, see the New Europe Center’s analysis ‘Security Matrix’[10] and the formats of Ukraine’s invitation to NATO[11].

- The new US administration and old friends. Building active communication with representatives of the new US administration. It seems that in the first months, the new US administration will try to restore dialogue with Russia, and there is a risk of limiting assistance to Ukraine. It is important for Ukraine to build communication with Trump’s cabinet, both directly and with the support of old friends (e.g., British former Prime Minister Boris Johnson).

- European emphasis. It is quite obvious that the US will reduce its aid, shifting the main burden to its allies in Europe. Ukraine needs to build its strategy with the awareness of limited resources, and diplomatic efforts should be directed at advocating for more support from the European side (not only the EU countries, but also the UK and Norway).

- Change of narratives. Reaching European politicians will be more difficult, as they are guided by public sentiment that is increasingly vulnerable to pro-Russian rhetoric. If ordinary French or Germans cannot be convinced that the Ukrainian war affects their interests, it will only be a matter of time before politicians favourable to Russia come to power. Ukraine’s previous message, which was to demand support by default, may no longer work. More active communication work is needed with audiences that favour quick negotiations without any strengthening of Ukraine’s position. Remind them, in particular, of the nearly 200 negotiations within the Minsk process that ended with Russia’s large-scale invasion.

- New opportunities. Ukraine should use new opportunities. For example, more involvement of South Korea in countering Russian aggression. Inviting military advisers from Seoul could give impetus to the French idea of sending European military instructors to Ukraine. It also opens a window of opportunity for obtaining South Korean weapons (South Korea has 3.4 million surplus 105-mm shells in its stockpile)[12]. The Republic of Korea also has stocks of Hawk, Mistral, and Igla air defence missiles [13]. In addition, Ukraine could ask Seoul to provide tactical missiles (such as KTSSM-II (South Korea’s equivalent of ATACMS), Hyunmoo-2 tactical ballistic missiles, or Hyunmoo-3 land-launched cruise missiles) [14].

- Partners’ investments in the Ukrainian defence industry. Ukraine should intensify negotiations on Western countries’ investment in the production of its own weapons. The European defence industry can help Ukraine and at the same time benefit from investments in Ukrainian production. It can also facilitate the transition to the production of more sophisticated equipment. More on this in the New Europe Center’s policy paper ‘Can Europe Stand Alone in Supporting Ukraine?’ [15].

- Continue efforts to confiscate Russian assets, particularly for investment in the defence sector. Since the implementation of most defence projects is constrained by a lack of available funds, Western countries must explore alternative funding sources. The confiscation of major Russian assets remains the largest untapped financial resource. A portion of these confiscated funds should be allocated to the joint production of defence products [16].

The material was prepared with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. The material reflects the position of the author and does not necessarily coincide with the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.

[1] Jay Ross, ‘Time to terminate escalate to de-escalate – it’s escalation control’, War on the Rocks, April 24, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/04/time-to-terminate-escalate-to-de-escalateits-escalation-control/

[2] Address during the Cuban Missile Crisis, 22 October 1962, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/historic-speeches/address-during-the-cuban-missile-crisis

[3] Ibid. (‘The 1930’s taught us a clear lesson: aggressive conduct, if allowed to go unchecked and unchallenged, ultimately leads to war’.)

[4] Harry Truman, ‘Years of Trial and Hope’, 1956. (‘If this were allowed to go unchallenged it would mean a third world war, just as similar incidents had brought on the Second World War’).

[5] Krauthammer, Charles. ‘The Unipolar Moment.’ Foreign Affairs 70, no. 1 (1990): 23–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/20044692.

[6] From the book “The Last Politician by Franklin Foer (‘The Last Politician: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Struggle for America’s Future’ by Franklin Foer): https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/31/books/review/the-last-politician-franklin-foer.html

[7] https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/09/11/ukraine-russia-war-biden-us-escalation-management-military-aid/

[11] https://neweurope.org.ua/analytics/yakym-maye-buty-zaproshennya-ukrayiny-do-nato/

[12] Defence Express, ‘South Korea has 3.4 105-mm artillery shells, which are crucial for AFU, and they should be provided’, 22 October 2024, https://defence-ua.com/news/pivdenna_koreja_maje_azh_34_mln_105_mm_snarjadiv_jaki_duzhe_potribni_dlja_zsu_i_jih_treba_dati-16955.html

[13] ILLIA Kabachynskyi, I., ‘South Korea Is A Major Arms Supplier. What Equipment Can Ukraine Receive?’, United24Media: https://united24media.com/war-in-ukraine/south-korea-is-a-major-arms-supplier-what-equipment-can-ukraine-receive-897

[14] Defense Express, ‘If DPRK sends over 12 thousand troops to Russia, then what are the missiles we need to ask for AFU from South Korea’, 18 October 2024, https://defence-ua.com/weapon_and_tech/raz_kndr_posilaje_azh_12_tisjach_vijsk_dlja_rf_to_jaki_raketi_dlja_zsu_varto_prositi_v_pivdennoji_koreji-16932.html

[15] Leo Litra, ‘Can Europe Stand Alone in Supporting Ukraine’, New Europe Center, July 2024, https://neweurope.org.ua/analytics/en-can-europe-stand-alone-in-supporting-ukraine-scaling-up-the-defence-industry-and-funding-defence-production-2/

[16] Ibid.